AGANETHA DYCK

[This essay was commisioned by the Canada Council for the Arts in celebration of Aganetha Dyck's reception of Governor General's Medal in Visual and Media Arts in 2007. Some of the thoughts in this piece of writing were first published by Toronto's C magazine, April-June 1996, 43.]

Aganetha Dyck was born in 1937 in Winnipeg, Manitoba to a Mennonite family. In the critical literature, which has been invariably positive, her art is often related to her rural upbringing and her life as a middle-class housewife.

Dyck is one of few prominent contemporary artists without an art school education: she is essentially self-taught. She had her first solo show in 1979, having arrived late to a full-time practice because of family responsibilities.

Since the late seventies she has shown her work all over Canada, in England, France and in the Netherlands. The Winnipeg Art Gallery organized a major touring retrospective of her work in 1995. In 2000, an important exhibition of her "interspecies communication" bee work called Nature as Language, curated by Dr. Serena Keshavjee, happened at Winnipeg's Gallery One One One, and in 2001 the Canadian Cultural Centre in Paris organized a survey that toured to Passages, centre d'art contemporain, Troyes, France.

Aganetha Dyck began her career working in a range of sculptural media that included wool, cigarettes and buttons, work that can be read as a kind of material history of post-war feminism. Indeed, domestic critiques can be easily applied to her art. Her early canned buttons are the product of happenstance (she once rented a studio full of buttons that had been a button factory) but also a transgressive dig at domestic chores like sewing. A set of shrunken sweaters laid out across a floor or a road could be about a washing machine disaster or an ironical celebration of children, or both. What looks like poisoned food and other substances in the amniotic-like fluid of Dyck's early Mason jar works is more explicit: this is canned food gone sour, a planned accident.

Years ago I saw a visitor wince as her friend whispered "ouch" at Dyck's intricately-made cigarette sculptures, which had been dipped, pierced, tied, twisted, and punctured with plastic tubes, electrical wire, miniature figurines and innumerable other tiny objects. Some of them looked like dimpled and stretched flesh, the detritus of some sadomasochistic ritual. Cigarettes themselves, without adornment, can suggest the tightened chest of a lung damaged smoker, but a viewer's throat also tightens in front of Dyck's cigarettes, instinctively reacting to the wire used to bind these little creatures up.

Dyck's work often returns well-known materials to a viewer as enchanted, uncanny objects: a cigarette becomes jewelry; shoulder pads become cabbages; and, in work that has occupied her for over ten years now, objects left for a good long time in the hives of a bee-loud glen return as Baroquely encrusted images of themselves.

The work has always had a surrealistic touch. Hal Foster's book Compulsive Beauty (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993, 25) says it all: "surrealism oscillates between ... two uncanny fantasies of maternal plenitude and paternal punishment, between the dream of a space-time before bodily separation and psychic loss and the trauma of such events." Or, to substitute the terms: Aganetha Dyck's art oscillates between the Queen bee and a last cigarette.

In conversation Aganetha Dyck champions "lateral" thinking as the basis of her work, an attitude to art making and life that has as much allure for some artists today as surrealist automatism (that is, automatic drawings and writing) once had at mid-century.

Technically, the artist uses mixed media techniques that have a storied history in contemporary art. She has long been interested in the late German artist Joseph Beuys. Her (earlier) use of felt, her longstanding approach to mixed media materials, and her attitude to artistic agency in the more recent work with bees all bespeak Beuys's influence.

Since 1991 Dyck has concentrated almost exclusively on the bee work, art making that involves placing ordinary objects in the apiary and allowing bees to create sculptures. Dyck speaks of bees as being her "collaborators". Like the results of surrealist automatism, the use of bees does not completely collapse distinctions between human agency and animal instinct into a work of art, but it comes close.

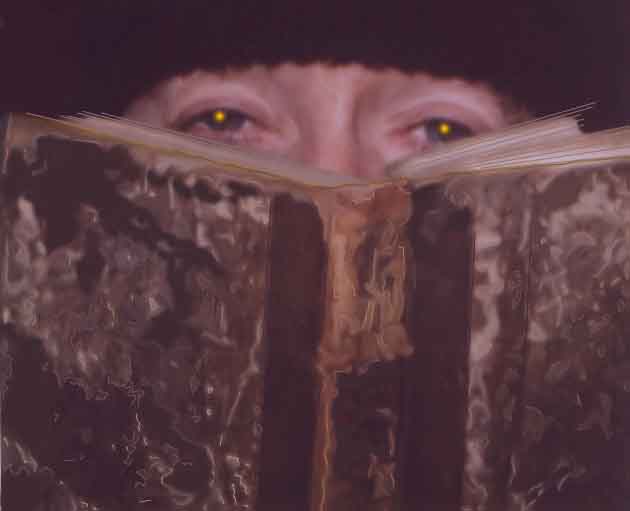

Dyck's art is rife with evidence of complex operations that get under one's skin and into one's brain. She once (in a show called The Library: Inner/Outer at Lethbridge in 1991) set a series of books, purses and briefcases dipped in bee goo together with objects appended to them on elegant tables and stands.

The candy-apple curves of Dyck's beeswax-covered things can recall Calgary artist Eric Cameron's Thick Paintings, but Dyck is plainly not as interested in the object as the residue of a material process as she is in the work of art as a glossy surrealist fetish. Dyck's surrealism thrives on the psychic effects produced when small objects like doll heads and smoker's pipes ooze up unexpectedly out of vulvic books and briefcases. Many of Dyck's works are given a treatment that recalls Dali's jewellery and Picasso's cubist collage. She turns every art procedure to Rococo ends, so that every Protestant meeting house of process art (however faintly visible its liniments) gets gilded into a Catholic cathedral.

Her 1995 retrospective exhibition at the Winnipeg Art Gallery rightly put an emphasis on the bee work. A spectacular piece in that travelling show was a honeycombed glass dress with a living bee hive attached to it, a work subsequently collected by the National Gallery. A Plexiglass tube ran from the Plexi-boxed hive to the sky outside the exhibition space so that viewers could watch the bees do their work. Newspaper reviews of the show played up this piece, and rightly so. One thought immediately of the British artist Damien Hirst, who has, among other things, stuck live flies, dead meat and working bug zappers in Plexi boxes. Like Hirst, and with a similar feel for a gothic surrealism, Dyck makes compressed objects in which the sources can be plainly seen, but not so plainly understood.

NOTES: As to when Dyck began to make art, a reproduction of her earliest surviving work Shrunken Clothing on a Road, 1976-1981, appears in the 1991 Southern Alberta Art Gallery catalogue: Aganetha Dyck The Library: Inner/Outer, Her 1988 Gallery One One One solo show catalogue Brain is Not Enough includes a reference to a Regina Leader Post review from 1975. Writers and curators who were important to Aganetha Dyck's career include Shirley Madill, Sigrid Dahle, Serena Keshavjee, Joan Borsa, Grace E. Thomson and Joan Stebbins.

|

|