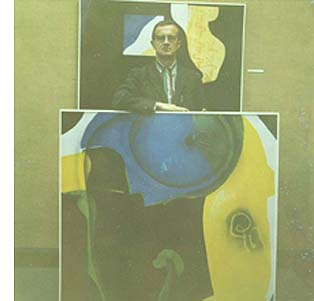

Works in the exhibition Back to first Mikuska page  Above: Frank Mikuska at the Yellow Door Gallery, Winnipeg, October, 1966 Interview with Frank Mikuska conducted and edited by Oliver Botar, January 2010 Transcription by Rachel Gartner OB: It’s nice to be here with you to talk with you about your career and your life and work. You were born in 1930? FM: Correct. OB: Your parents were from Slovakia? Can you tell me a little bit about them – where they came from in Slovakia, when they came to Canada? FM: They lived northeast of Bratislava in several small communities. It’s sometimes hard to figure out what these communities were – it was mostly agrarian. The family had some land and they were farmers. I don’t have a lot of direct knowledge of everything except that my dad had five brothers and somehow they managed to immigrate. I guess that Dad – when he was seventeen and a half or so – he became involved with the Hungarian Army. As you know the Hungarians took over Slovakia a long time before that, but they were having problems with the Serbs in so-called Yugoslavia. He spent about two and a half years in the army and he became sick and he was in a clinic for about eight months. OB: Was he injured in the war, or did he just get sick? FM: I think he had some kind of viral medical problem and the way he puts it, the doctors really pulled him through. After he left the army, he decided that he would pick up where he left off. My mother met him there – her name was Kajan. My Dad got the idea of immigrating because his family had already begun that process. OB: It seems like an interesting time for a Slovak family to immigrate. Slovakia had just become independent, part of the new country of Czecho-Slovakia. You would think that was a time of optimism – this new-found independence and immigration just seems to me to be an unusual idea at that time. They must have had some other reason – economic maybe? FM: Economic, but you have to understand that at that time in those countries, there was that problem of the eldest being the heir and my dad was down the line, so he could see that if he wanted to do anything, he would have to leave. I think that somehow they were being encouraged to do that, because you could see that there were political movements that he did not want to get involved with. So he immigrated through Canada and that was about 1923 and he wanted to go to the [United] States, but they had filled the quota already. OB: There were quota systems for central Europeans at the time. FM: That’s right. What they wanted mostly, were farmers because they were trying to fill western Manitoba. They would give them some land… He was not in any position to homestead and he began by working in the forest. He got hired by a pulp [and paper] company in northwestern Ontario, and so he was part of that whole scenario – there was a lot of clearing. Houses were being built like crazy and the pay was substantial and so he decided to do that. He turned out to be intrinsically one of the best finders of the type of material – white spruce actually – that the people wanted and all of these people lived in the bush. The companies built bunkhouses and that’s where they stayed probably all winter … OB: How did he end up in Winnipeg? FM: These people did no forestry work during the summer – so he ended up in Winnipeg. There was a small community of Slovaks here, but they were mostly on the farm. But in the area that he settled in it was a real ethnic group. You could name whatever country you wanted and people were there. The reason was because the CPR brought people in and they lived in a community that was adjacent to the railroad. So, during the summer he found other things to do. He was tied into the religious element – the Roman Catholic Church – and so he found things to do. OB: Was there a Slovak Roman Catholic parish here that he could be part of? FM: Not at that time, but later on he was part of building a church here in Winnipeg. OB: How did he meet your mother? FM: Well, I don’t know. He never told me about it. I guess the families would be living fairly adjacent to each other. OB: In Slovakia – so they came here together? FM: No, she came with my oldest brother, who was – let’s see – when he came he was just going on five years old and then after that there was a period of time when there wasn’t any thought about family growing – and so in 1929 my other brother was born, and then following that was me, and then my sister. OB: There were four siblings in the family? FM: There were – my mother had lost three other babies in Slovakia. OB: Was there ever any interest expressed in art – in folk art or any kind of art – in the family? FM: Church art. OB: Can you tell me about that? FM: Well, the church that we belonged to was, of course, elaborately painted on the inside with all kinds of religious icons. OB: This was already the Slovak church? FM: No, this was the English Church. Paintings, murals, the whole thing was decorated. OB: Do you remember which church that is? Is it still around? FM: No, it burned down actually, years later. It was the Immaculate Conception Church in Point Douglas, which is, I would think, just two or three blocks from the CPR, where I grew up. OB: It was a wooden church painted on the interior? FM: Yes. OB: Do you remember the paintings? FM: Yes. It was quite attractive. But I never looked at it consciously – from the point of view that this is what I want to do. It was interesting from a religious point of view. That was probably, realistically, the only art I ever saw. In elementary school I had a teacher, a nun – it was a nunnery actually – and I was being encouraged by this teacher. I used to like to doodle around and she saw that there was some interest there, so she encouraged me. We did a few projects with pastels and things like that. They were very minor. OB: Do you remember her name? FM: No, no I don’t. OB: Which school was this? FM: It was the same as the church. OB: Did your parents have to pay for that school? FM: No, my dad would get up at three in the morning, and he would go over to the nunnery and fire up their furnace. Then he would go over to the school, which had two furnaces, and he would fire them up. Then he would go over to the rectory and do the same there and then he would end up at the church. So he spent his time every morning making sure that the heat was on. That’s how he actually paid for it. Eventually, he ended up at St. Paul’s College, which was in downtown Winnipeg at that time and he was doing the same thing there. OB: This was when you attended St. Paul’s? FM: Well, I attended St. Paul’s just briefly, for a year and a half. I dropped out just midway through grade ten. OB: Why did you drop out? FM: Lack of interest. The hardest part, for me I think, was that we spoke Slovak, and when I started school it was difficult. The only English I knew was what I learned on the streets and it wasn’t exactly couth all the way through, you know? My early education was ridiculous because the school held me back through grade two going into grade three, and then they held me back farther. They held me back three times and my sister, who is two years younger than I am, I graduated with her. It was not a very good situation. OB: Do you think this was because of your lack of proficiency in English or do you think it was because school just didn’t agree with you? FM: Well, I think part of it is partly true for both sides. It was difficult to learn to cope with English in terms of schoolwork. It’s not that I didn’t have any interest, but outside of those religious things, I never read – I couldn’t read – in the sense that I had no interest in reading. The environment on the outside was such that there was no push to read. There was hardly anything around. OB: Did your parents read? They must have gone to school. FM: Their level of education was at about the grade six level back home. I don’t think that was enough. I don’t understand it because I wasn’t born in Slovakia, so I don’t know. My mother never learned to speak English. She understood – she finally got around to understanding what people were saying. My dad was out working. He was always out looking for jobs. He finally got tied in with the Winnipeg Electric Company, whose mandate was to put in telephone poles for communications and also for bringing electricity into the city. OB: This building was in Point Douglas as well, right? FM: Yes, well, that was after the Manitoba government took it over, then it became Manitoba Hydro, but in those days it was Winnipeg Electric. They had a lot of lines for the streetcars and all that sort of stuff. Dad had quite a good reputation in the company, so naturally they would keep him on. He was very good at solving problems and he worked like a slave. You would never move up unless you had an education, which is really what was the problem. He was very good at mathematics and I could never understand mathematics and I think it’s probably because the teaching methods at that time were not up to standard. I spent more time in church than anything. OB: So you found it was very religious? FM: Yes, they were. OB: Do you remember any of the members of your family engaging in artistic activity? Did your mother embroider or sew? Did your father carve wood, or whittle or anything like that? FM: No. I mean, he was good at what he did, but he didn’t have any concept of making art. My mother was too busy filling up comforters with feathers to get involved with art. The things were maybe one foot and a half deep. It was cold in those days. The heating in those houses was pretty simple: they were heated by wood stoves, and then they ended up with these great big furnaces in the cellar. OB: Is your house in Point Douglas still standing? FM: No, but we used to move around a fair bit. The house that I was born in – it’s still standing although it’s been refaced. It was quite a district, mostly known for minor squabbling between ethnic groups. Nothing overt, but I can remember there was a park at the corner of our street and every Friday evening there would be men out there putting up a stage and it was a debating thing. At that time in the city the conflicts were kind of iffy because of immigration. We were caught up in it because there was interest, and we would run down there and listen to what they were doing. Chances are there would be a squabble now and then. The police would come running down, you know, that sort of thing. Outside of that, the community was sort of separated along ethnic lines. OB: Were there enough Slovaks there for your family to be involved in a particularly Slovak ethnic community? Who did they align themselves with? FM: Well, I think in a favourable sense, we aligned ourselves with almost anybody – it was the way. You couldn’t get along without that. It was an era when the young people were always forming their own little alliances and through no interest at all on the part of adults these kids would usually get into trouble. It was fertile ground for juvenile delinquency, really. Across from this parochial school that I went to there was a public school and the kids just didn’t get along: tossing stones at each other and that sort of thing. OB: These were “cat-licker – pot-licker” types of fights? FM: Yes, that’s right. Yet, the Ukrainian community – and there were quite a few Ukrainians in that area – they built themselves a couple of fine churches that are still standing now. The young people got together. Actually, there was a quiet time then, you know? OB: What do you remember about the Second World War, because you would have been about nine or ten years old when it started and fifteen or so when it ended? FM: Well, my older brother – he got himself a franchise from the newspaper people. So, during the war we would be running up and down the street yelling like crazy “Extra! Extra!” you know? Whatever battle, some ship sunk, or whatever. Otherwise part of his job was on one particular corner on Main Street, he’d have a stack of papers and we would be selling them. Of course all of the money came back to the house. That goes back to the tradition from the old country where the family supported the eldest and so you were encouraged to do a job, whatever you could do. OB: Do you remember ever going to the Winnipeg Art Gallery as you were growing up? Did you know that it existed? FM: I knew there was a museum, but no. OB: How was it that you ended up enrolling in the Winnipeg School of Art in 1947? You must have been seventeen years old. FM: Well, there was an event that happened. My oldest brother who came back from the War, in 1947 at the age of twenty-two, he worked for Manitoba Hydro and he was electrocuted and it just turned out that it had a very substantial influence on what was happening in the family. I was at odds – I didn’t know what I was going to do. The family just got the idea that if I was ever going to get anywhere I had to do something, so that was the thing I chose. It was quite easy to access. At that time the Winnipeg School of Art was a private entity and so they paid for me to enroll. OB: Who paid for you to enroll? FM: The family. OB: How did you get the idea to even try the School of Art? Had you heard about the School of Art? You were seventeen years old. You had never been to the Winnipeg Art Gallery. FM: I didn’t have any skills for going out and getting a job. At that time the conditions in the city were such that the older men – the people that needed jobs – couldn’t get them. So I never stood a chance. I never had the skills. They knew at home that I was doing better drawing at school. There were indications that if I was going to do anything, that might be the best. Academics were not in my view. I don’t know exactly why – still. It still bothers me today, but getting past a certain point was very difficult. When I started with the Winnipeg School of Art, it was pretty simplistic. The teachers took you into class and sat you in front of a still life, or they pulled in a plaster cast of some romantic hero in a classical theme, and you would sit there and draw it. At first, I couldn’t draw worth a damn, and perhaps it took me a long time to adjust to that. For one thing, I had a forty-degree squint: my left eye was turned in and perhaps maybe that was part of my problem. The kids would always look at me and they’d say “who’re you looking at?” or you know “you’re cross eyed” and all of that sort of stuff. To this day I lack binocular vision. But anyway, I persisted in that and eventually I caught on to doing a few things. OB: When you first arrived there – if my history is accurate – Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald who had been the Director of the School, had just gone on sabbatical [1947], so he wasn’t the director when you began. FM: Joe Plaskett had replaced him. OB: Did he teach you at all? FM: No. I never met Joe Plaskett. I don’t think anybody in the school ever met him except for the people who were doing the teaching. He probably spent most of his time in his own studio and he had to answer to the Board I guess. OB: Do you remember who your teachers were at first? FM: Yes, there was a teacher named Edna Tedeschi – she was probably senior – and then there was Cecil Richards, who actually ended up teaching sculpture when the University took over the School of Art. There was a registrar whose name was Gissur Eliasson and he was one of these very kindly people. If you needed any supplies he would smuggle them to you, you know? They would take us over to the Museum, where the Art Gallery was. But they were more interested in the Museum because they would sit us in front of the displays and we would be drawing birds and stuffed animals and stuff like that. OB: There was an art collection at the School of Art – there were works of art up on the walls. That must have been one of the first times you saw art other than church art. FM: We saw calendar art. Calendar art was always a joke though. It was more interesting being in a church at that time because you were with the spiritual. In a sense I suppose it had a great deal to do with what I recognize in terms of my artistic development. OB: At that point I assume you were going to church on Sundays with your family. FM: I was at church every day. OB: At your school they said mass every day? FM: Yes, it was early in the morning. When my father went out to fire up the furnaces, the priest always said mass at the nunnery at four-thirty in the morning. I was an altar boy. So I had to be there. OB: So, at the School of Art, there was art on the walls. For example, I know that Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald bought an abstract painting from his friend Bertram Brooker – Sounds Assembling – which is now in the Winnipeg Art Gallery and that must have been up on display. It was around that time that he bought it – in the mid-forties – maybe just slightly before you came. Do you remember seeing that? FM: If I saw it, then I don’t remember it because it was hard to understand. We were being taught things that were traditional – in the classical sense, you know? Drawing plaster casts and that sort of thing. Until the University took the School over and [William Ashby] McCloy came in 1949 and explained the whole concept of art and making art, I never understood any of it, Impressionism, the New Wave in New York, that sort of thing. OB: So, you were a student at the School when the School became a part of the University, otherwise, it would have been difficult for you to enroll in the University given that you hadn’t finished high school. FM: Absolutely. I was a drop-out. OB: You were lucky in a sense that the School of Art was absorbed into the University, and became a unit of the University. FM: Of course. OB: How do you remember that transition? The building of the School stayed in the same place… FM: Yes, but the attitude was different in terms of the teaching staff being willing to recite in a sense, the newness of it, why they were there. We were flooded with ideas and images that we had never thought about – this whole business of Modernism. OB: People weren’t talking about Impressionism or Cubism or Abstract Expressionism? FM: That happened after the Americans came. OB: So you remember a sharp division from before McCloy’s arrival to after? FM: Of course. There were individuals – Tony Tascona for instance – in the reserve army, and when the War ended, all these people in the army didn’t know what to do, and the government started paying for education. The School of Art was the easiest way to get in. Whereas the implication was that when the University was to take it over, there had to be standards. The standards were presented in a sense that was understandable. All of the sudden, people caught on – I caught on – that whatever I presented was open to debate and criticism, but not stringent criticism – mainly encouragement. The professors that they hired were all different. They had different personalities, and you almost could pick and choose who you would like to study with. OB: McCloy, if I remember correctly, hired John Kacere and Richard Bowman in 1950. Did you study with either of those two, and are there other people that you remember? FM: Yes, and there was Robert Gadbois and then they pressed Gissur Eliasson into teaching because he was very good at calligraphy. OB: Cecil Richards was there as well? FM: Yes, he was there. OB: Who did you choose? FM: I chose Robert Gadbois. He was a painter himself [but] most of his interest, in his life, was in the commercial [i.e. advertising] industry. What better excuse to learn a skill that you could probably get a job in? I didn’t even think about it at the time but I knew this guy could show you how to do things – not just concepts. OB: So he was a graphic designer in a sense? FM: He was a graphic designer in a sense. I can’t count how many people – maybe a half a dozen, were interested in getting into a commercial design job because the printers were using lithography, whereas nowadays they’re using digital cameras… The major department stores were printing catalogues and they needed people to draw shoes, or whatever they were selling. There were job prospects. But I could never see myself doing that because I had no interest in drawing shoes or clothes at the time. I was more interested in the ideas that Robert Gadbois was presenting. There were changes that were taking place in the whole graphic [design] industry; it was sort of adjacent to what was happening in the fine arts. The division didn’t exist for him – that the whole face of making images – there was no division. OB: You mean that there was no division between the applied and the fine arts? FM: That’s right. OB: Was he a Modernist himself – in his work? FM: Yes he was, he was a very good painter. OB: In his graphic design was he a Modernist? FM: Yes, absolutely. At that time even the printing industry was looking for changes. I think that came out of the vast machines of education in America … he came from Iowa… OB: …the same way John Kacere, Richard Bowman and McCloy came. FM: Well, McCloy hired him. I don’t know exactly where Kacere came from, I think from somewhere in the Midwest. OB: They went to the University of Iowa. FM: Did they? Bowman, of course, he was the most Modernist of them. His paintings show it. He created large paintings and you could tell he was probably the most advanced in terms of what was happening in the New York School. There were a lot of people at the Art School who centered around those people because of the excitement. OB: As far as I know, Bowman was associated with an English painter by the name of Gordon Onslow-Ford, who was a Surrealist living in Mexico during the nineteen forties. He published a magazine called Dyn, which was internationally well known, and Bowman went down to Mexico where Onslow-Ford was living and became associated with him and then went to graduate school in Iowa, This was a kind of a mystical Surrealist group that Bowman was involved in – it wasn’t the New York School – it was a very different group. Did you ever get any inklings of this? FM: In my mind there was no imagery. Colour Field and breakdown. It’s almost like if you wanted to enlarge a Seurat and blow up a part of the images that he was making, in a pointillist sense. That was what Bowman was painting. OB: Do you think that his paintings were the first completely abstract works you had ever seen? FM: Absolutely. People gravitated toward other artists in the school as well, for example John Kacere. OB: Was he also working in an abstract mode at that time? FM: Yes, but mostly in – I forget what word – his influence came from, but it was the New York School. It was kind of related to even things I am doing now. I couldn’t get close to Bowman and Kacere because there was always a crowd around them. OB: Who was in that crowd? Who was interested in Bowman amongst the students there? You mentioned Tony Tascona. FM: I’ve got a whole list – there was Tak Tanabe, Ivan Eyre, Bruce Head, Don Reichert, Winston Leathers, and so on. They were fired up. OB: Don E. Strange? FM: Don Strange, yes. But Don was sometimes there and sometimes not there. He would sit down and give you an exploded view of say a radio or a mechanical thing. He worked for the aircraft industry… OB: Do you remember who was associated with Bowman? Which students gravitated toward him? FM: Well, people like Bruce Head, I think that is fairly obvious, right now, in the way that Bruce has been working. I studied mostly with McCloy and Gadbois. OB: Tell me about McCloy and how he taught. FM: The interesting thing about McCloy was that he worked in encaustic and the paintings that he was doing were just – wow. The guy could really paint. Who ever heard of encaustic in western Canada? He came onto something really new. That impressed me. He’s the one that went around to every class in painting and talked to you about your work. I enjoyed his opinion – he was very good. Gadbois, of course, for me that was a no-brainer. I caught on to him. I liked his teaching style, and I liked what he was presenting. My connection with the other profs was the fact that they liked jazz, and I was just getting caught up in jazz and it was phenomenal. Kacere spent a lot of time in his studio and you could hear him playing the drums. And Bowman was playing music. There was a big impetus. OB: So these Americans came in bringing new music, bringing new approaches to art, new attitudes, new media in fact. So it was kind of a revolution at the school, wasn’t it? FM: It was indeed. Did you ever read McCloy’s opening gambit to the people who went there? OB: At the time of the scandal? FM: It was always a scandal – what with all the new things. I guess that’s what he was doing: he was leading a rebellion in a sense. I think Winnipeggers always needed some kind of a stun. I mean after all, they had to follow up. The big event in Winnipeg was in 1919 for Christ’s sake. They had had the big strike, and people were just looking for change. The ones that had any sense at all – instinctive sense – would be looking for that. OB: So what do you remember learning at that time from this revolution – from this American invasion if you like – about modern art? How did it change your view of what art could be? FM: Well, for one thing, it gave me a sense of being able to exercise some kind of inquisitiveness. At this stage, it’s hard to sort out. A lot of people were committed to the change. At that time some people were quite successful, and others were just strictly experiencing ways of doing things. Experiencing, for instance, just the act of printmaking – which, at that time, was unknown. OB: There had been no printmaking at the School of Art that you know of? FM: Minimal. OB: McCloy came from the University of Iowa where printmaking was very current, and modern printmaking, taught by Mauricio Lasansky, was current. FM: He brought some of it. There was some at the Winnipeg School of Art. There was very little in terms of equipment. I think that prior to the University taking over, Brigdens had a lot to do with bringing the well-known artists at the time, so that they could use the equipment. OB: What are your memories about student life at the school? FM: The [American] professors were known to invite people over, to party or just talk. They were like that. They were open. OB: Do you remember being in anybody’s home? FM: Yes, and I think Gadbois was probably the most successful. You could go to his place by invitation, and [it was] sort of open ended, you know? “Come on down!” He invited quite a few people. You’d walk in there and he’s painting a mural on the wall. What better way to break the ice? He was a “jazzer” so to speak, so there was always good music. His wife Ruth was very interested in promoting this. We had a good time. It was very good. The level of confidence between the students and professors was increasing all the time. Bowman always had three or four or a half-dozen people talking with him, walking around with him. There was a small restaurant on the corner, with maybe six seats in it, and during the World Series, they’d all march down there and have lunch and enjoy the baseball. It was a good relationship, very good. Whoever chose those particular people had a very good sense of what would make it go. OB: Now if I think later on, of the artists that came out of the school at that time, you’ve mentioned some of their names: Takao Tanabe, Tony Tascona, Bruce Head, and Winston Leathers – were these your friends already, then? FM: No, because [except for Tascona] I was at the Winnipeg School of Art, before they even showed up, and I was a reticent person anyway. I was probably very much a loner. That probably describes my younger life. It was very difficult breaking in because once people make up their mind, it’s almost like a gang mentality, but it’s not a gang. It’s a little enclave so to speak. Then, new professors started to show up because there were more and more people coming in. So it was a terrific mélange of ideas and alliances, that sort of thing. Like, I’ve heard before “no, you didn’t start that! It was so-and-so” you know? It was kind of angling for preference, or whatever. OB: After you graduated in 1951, you got married fairly soon after that: ’52 or ’53? FM: It was 1953. OB: How did you meet Shirley? FM: Well, Shirley’s brother was at the Winnipeg School of Art. His name was Arthur Stevens. Dr. Arthur [D.] Stevens. He eventually left Winnipeg because there was no Master’s program here, and he was more inclined towards academics although he was a painter as well, but he was more interested in the ideas, in art history. So he took his masters at Indiana [University, Bloomington] and eventually got his PhD in art history. Initially he taught for two years in Arkansas, then he ended up in Claremont, California with one of five colleges there. OB: There must not have been that many Winnipeg boys that became art historians in those days. That wasn’t a usual, or common, career path. He lives in Claremont, California, which is part of Los Angeles, forty miles out. He’s Emeritus now. OB: We were talking about your marriage. FM: Yes, so we were walking down Portage Avenue one day and somebody was calling “Arthur,” and it happened to be Shirley. She thought I was somebody else. That didn’t last long… Shirley went through teachers college, and she started her career as a teacher out in the country. She used to come in and Arthur had a rental with another friend, so that is where we always met. If it wasn’t there, then we would meet at Robert Gadbois’ place . OB: By 1954, CBC television was set up, and the following year you already got a job there. How did that come about? FM: That was the advent of television in this part of the country. There was another colleague [at the CBC]. His name was Dave Strang, and he also went to the School of Art. Anyway, 1955 is when I joined the CBC and I joined as an apprentice. McCleary Drope [attended the School of Art 1950-54] was already working there and then I came along, and then Bruce Head, and I was still an apprentice, but they took him on because McCleary Drope chose to think that Bruce Head had more talent than I did. I had to learn the business before. What the hell. Mac [McCleary], Bruce, and Winston Leathers, they were, you know…? I just kept my mouth shut and went on with it. I had to learn the business because we were presenting black and white TV and I had to learn how to transfer coloured images into black and white. Very serious you know? You’d have grey scales and that sort of thing. It was actually very funny at times because the set designer and people like that very seldom took much interest in establishing that fact: that colour [had to be converted in]to black and white. You’d have to sort of jump around. If someone was wearing a red dress, for instance, sitting on a red couch, all you could see was the head because the rest disappeared. I was in the graphics department. We would do station identifications and if the producer came along and wanted a story illustrated, then we would do that. It was quite broad.When they figured [that] they should give me a boost, they bumped me up to designer status. Really, it was because I needed more money to live. OB: You were working in an atmosphere with other artists. You were working with McCleary Drope and Bruce Head. Was Bruce a friend by that time? FM: That’s another story. If you want to read about it, it’s in the obituary (OB: Bruce just passed away recently in December 2009). Bruce with his Scottish background and the schools that he went to (Daniel MacIntyre in the west end), which was upscale from where I lived, so naturally, they had art instructors, and stuff like that. So, really, he was a jump ahead in a lot of things. He had one summer with W. [Walter] J. Phillips at the Banff School, so he was ahead. OB: On the other hand, Tony Tascona was from a poor Sicilian family in St. Boniface. Did you feel at all left out because there weren’t any people with a similar background to yours at the school? FM: My being left out: it always had a cultural connotation. OB: Can you talk more about that, or be more specific? FM: I don’t know. I was always getting pushed away. So I had to sort of develop a self-sense and I can remember if I wanted to enjoy the winter for instance, I would be outside all of the time. I would put on my moccasins and I’d be up to my ass in snow or whatever and I’d do everything by myself. I couldn’t interest anybody else in doing that. OB: What about your brothers or your siblings? FM: No, they weren’t interested. I did the usual things that kids do. I learned how to play hockey, starting at first without skates. My childhood was wild from that point of view. As long as I wasn’t tied in with school, I was okay. You’d get a bunch of kids together, and they’d just want to have fun. But I’m talking about that time, after supper, when the dark came in. There weren’t too many kids around. I just loved roaming around. OB: Your parents allowed you to roam around after dark? FM: Yes, I guess they allowed me to but they never saw any harm in it. I think maybe that was probably the biggest thing. So I took on that persona. OB: Of being a loner? FM: Yes. OB: What did your family think about your career as an artist, going through art school and then afterwards getting a job at the CBC? How did they relate to this? How did that – if at all – change your relationship with your parents, brothers, and sister? FM: I guess it changed it somewhat. I always felt that they kind of resented some of that because they were paying for it. It bothers me even now, but just in retrospect. It wasn’t a very happy childhood, as far as I am concerned, except for when I was doing those things all by myself. OB: But did your relationship change after you finished art school and got a job? Did you remain on good terms with your family? FM: I think so. My brother decided that he would move away from the city, so I kind of lost him for a period of time. My sister was already doing very well in school and she went to a Catholic entity – St. Mary’s Academy. She was very good. Her marks were tops. OB: She got a scholarship at St. Mary’s? FM: No. OB: Your parents sent her to St. Mary’s? FM: Yes. That’s the way it went. If the parents couldn’t do it, then somebody else always stood in. There were some very generous people. Later she worked for Air Canada and she had a very good job. OB: You ended up staying at CBC for thirty-seven years, correct? That’s a long time. You won an award for animation, and an award for… FM: The Prix Anik Award. That was a national award. Dave Strang and I took on a project, as a… he had a certain outlook and I was a wild bastard. I could go any way. My artistic sense by that time had developed to such a point that I didn’t mind competing with what people were doing with computers. I always felt, and I think Dave went along with it, that we could do the equivalent in quality. OB: Through traditional animation methods? FM: Yes, sure. We took the project on, and we submitted it to the Anik Award for experimental stuff. There was a photographer – he was a very good photographer, and there must have been half a dozen computer animations and we scored all of them. OB: You taught for a time at the Winnipeg Art Gallery’s Saturday program. FM: I remember the Saturday morning class. That was about the point that the elementary schools were beginning to develop art classes. At that time they started having people who they would hire that had a second skill. Then they would refer them to the [Winnipeg Art Gallery] art classes. That was interesting. I wanted to do it because even though I had no intentions of being a teacher, there were lots of things that were happening because of this grand takeover by the University of the Art School. [Because I was still at art school] I didn’t have much time. It may have been [only on] two or three [occasions]. When I first saw Wanda Koop, she wanted to be active I could tell, because she was always working. There was no such thing as just sitting there and thinking about what to do. One of the things that really struck me – I could see the way she handled materials – [was] that she was in fact wasting her time because [like] the other individuals around her, all she was doing was cartooning like the old comic book art. So I talked to her and I told her “look, you have enough of your own talent that you don’t need to copy. So why don’t you start drawing things that you might like to draw.” And she did that, and in no time she was drawing objects. She had good skill. She took it to heart. OB: Have you stayed in contact with her? FM: I’ve seen her since then, even after I left the art school I always saw her somewhere. Funny that this should come up this way. [In 1953] the [Winnipeg] Art Gallery decided to bring in Ferdinand Eckhardt [as Director]. That was a change because he was more in tune with Europe. I got into serious trouble with the Art Gallery, however. McCleary Drope was very adamant about the fact that he wanted to challenge Ferdinand Eckhardt, because the artists in the city were not being fostered. The art at the Winnipeg Art Gallery, well, I don’t think it came along as quickly as what was happening at the Art School. We wanted [those in the Gallery] to accept what we were doing. In a sense they started doing that, but as you know, artists are always on the edge [and we thought] “why aren’t they paying attention to us?” You could tell that Drope was in a rebellious mood. And in a sense, I was too because of my experience of living in the North End… That’s one reason I often say I was probably headed for being a juvenile delinquent. There were gangs there at the time. Mac was just itching to change things. He finally got around to asking me, because everyone was telling him to quiet down – what are you talking about? – things are starting to happen and you want to stir the pot? At the time I was working at the CBC, he was too, and anyway, we had a short interview on a show called “Spotlight,” a current affairs kind of thing. We arranged to go on air and talk about this whole problem. OB: You were publicly criticizing Eckhardt for not having a close enough connection to the art community in Winnipeg? FM: Mac was sort of an urgent kind of guy, and he wanted to get ahead with it. I don’t really remember what the dates are. At any rate, Mac wanted someone to go with him. We both worked at the CBC at that time [1955] and so he saw that as an opportunity to go ahead. He needed someone not only to prompt him, but to support him in some way. I didn’t think it was such a bad idea anyway- getting people to understand that the art community is concerned with not being paid attention to, that sort of thing. I never saw [Eckhardt] come over to the Art School or anything. OB: What was the reaction on the part of Ferdinand Eckhardt and the Gallery? FM: I can’t remember but I’m sure there was because at the time they had a very strong Womens’ Committee and they didn’t like that too much. It could have been seen as a negative, rather than something positive. Years later there was a show at the Winnipeg Art Gallery, it was called Painting in the Fifties [Achieving the Modern: Canadian Abstract Painting and Design in the 1950s, The Winnipeg Art Gallery, 1995)… There was a new curator [Robert McKaskell]. He took it on – he wanted to do it. I remember going to the opening of it [FM had an untitled abstract oil painting on canvas of 1955 on display in the show], and strangely enough, there was a big crowd. Who came walking toward me? I spotted her – it was Wanda [Koop]. I knew that she was coming over to say hello and she had another young woman with her. So, we said hello and I kind of said “Aw, come on Wanda, I didn’t do anything for you. You had the talent and I just pointed it out.” This young lady – Wanda introduced her to me – and this young lady said (mind you, this was 40 years later): “Oh, you were the one who criticized Ferdinand Eckhardt.” OB: She read about it? FM: How could she have read about it? It was passed on. She was somebody’s daughter. I guess somebody in the [Womens’] Committee was still mad about it. OB: You got a job in 1955, but on your own time you were painting? FM: Yes, I continued to paint. But when I joined the CBC the materials were there – I didn’t have to search. So, I began to do things in a more abstract sense. OB: How would you describe this work? FM: Fantasies. The images were fantasies. OB: Richard Bowman and John Kacere had been doing abstract work at the School. They left by nineteen fifty-four, went back to the United States. What is it that you were looking at, why was it that you were moving toward abstraction then? FM: Gadbois was the impetus behind that. OB: Even though in his own work he was not abstract… FM: No, he wasn’t abstract but he was contemporary – modern. While I was still at the art school I had developed this technique, what I termed “lift drawing” and there’s some semblance to that in some of the works that came up in magazines: Miró, the quality of lines and I know that he wasn’t doing lift drawing, but I was doing lift drawing. It caused quite a stir with most of the people going to school at that time. I can still remember quite a few people who were just wowed about doing this lift drawing. OB: Can you describe the technique of lift drawing to me? FM: You ink up a plate, or whatever. Mostly glass. It could have been anything. Then you would block out an area that you wanted to confine your drawing in. Then you would put a sheet of paper on top of that and from the backside of the paper do your drawing. It would all depend on how much ink you left on the roller. It had a very special line. The technique kind of whizzed through. A lot of the students there picked it up because even if there was just a way of doing something – drawing or whatever – they saw the quality, and some of them picked it up. OB: You introduced it? FM: Yes, I introduced it and that particular work [the Gadbois work that Frank Mikuska donated] was his kick at doing that. OB: So, you were looking at Miró. Who else were you looking at? FM: I was looking at Modigliani and also some of the classic painters as well (not in the modern sense). Then of course it carried on into some of the Impressionists. OB: Do you remember when you became aware of the American Abstract Expressionists? FM: No, I don’t remember specifically. But I couldn’t see myself trying to absorb things that were being done in the field. I was too busy trying to develop my own imagery. It really never bothered me. I didn’t even make a real attempt to study anybody. I was going on my own way. That seemed important for some reason. I wanted to introduce colour and so I left this lift drawing stuff behind, just to move on. Ink was always my preference. From the very little experience that I had in printmaking, I got the idea that ink was a material to work with. I could handle it very easily. It had properties that other media did not have. OB: What were those properties that attracted you to ink? FM: For one thing, it was a lot easier to form volume, to add colour without killing the impression of the image, much like oil. I could do the same with oil paint, but oil paint just takes much too long to dry. So, I just moved on. OB: Did it have anything to do with your interest in graphic design, or because you were using it so often? FM: It came on because I moved out of the Art School and went into the real world. OB: But your favourite professor was Gadbois and he was teaching graphic design, so that was already in the School. So he must have introduced you to working with ink? FM: No, I don’t think so. I can’t recall that. He did introduce me to some of the water-based paints. Some of the images that he was using as examples, for one thing it was all printed material, but you could imitate that sort of brushwork and stuff and the kind of freedom that it takes to work with brushes or other tools: pieces of card and stuff like that. It was far more interesting for me to try to imagine certain effects, rather than sticking with one particular type of material. OB: You started showing regularly in the Winnipeg Show in 1957. By the nineteen sixties, you were showing elsewhere as well. As far as I can tell, your first major solo show was at the Yellow Door Gallery in Winnipeg in October of 1966. You showed ten ink paintings – large ones – and you showed a couple of them lying horizontally on tables… FM: No, on the floor. OB: Why did you choose to show them on the floor? FM: Well, whenever I went into an art gallery, I saw people looking at work that they’re not used to, mostly modern work and so they’re walking around trying to absorb what the paintings were all about. I got the idea that if I laid them down, then people would be able to freely walk around them, and people would get a much better idea of what some of the problems of constructing the work compositionally were. I just took it as an experiment. OB: Did you mean to imply that there was more than one way you could orient the work on the wall? So that if somebody bought one of those works, they could choose which way to orient them? FM: Not necessarily because I think at that time I always indicated how it should be hung. But as an experiment, and in a gallery, they would have more impact. OB: In an interview at the time [October 1966], for the Winnipeg Tribune, you said that if you had had enough space, you would have displayed all ten of those paintings horizontally. Could you imagine a show now that would show all of those works horizontally? FM: Well, at an exhibition I just had at the Scandinavian Centre [in Winnipeg ], some of the works were on tables and others were displayed vertically. So I guess I just carried over from that earlier experiment. With very little movement, the person could walk around and see all these different things and examine the work from a very different point of view. I think the viewer sometimes needs that kind of subtle force to move around and have a look. OB: Can you tell me a little bit about the Yellow Door Gallery? Who was the owner and the operator? Do you remember? FM: The operator was a lady named Irene Walsh. She was the wife of a very well known lawyer in town and she emigrated from Hungary, so she had a lot of research in her head already. She had an intention of waking up the people that normally go to galleries – the Winnipeg Art Gallery for instance – to show them there was other work that was being done that was worthwhile seeing. She eventually took our work to Expo when it was in Montreal. OB: In 1967. One of your works was acquired by the Museum of Fine Arts in Montreal. So that was her doing? FM: Yes. OB: It was in February of 1966 that you and Bruce Head had a two-man show at the Confederation Art Centre in Charlottetown and as a result they bought an oil on masonite painting by you – so you were doing some oil paintings – called Construction Number One. Is she also the person who took your work to Charlottetown? FM: No, Charlottetown was part of a plan, I think it originated in western Canada because there was a Western Canada Art Circuit and also there were people who wanted to extend that to the Ontario Art Circuit. It probably happened because of the travelling exhibitions that we had. I also think that perhaps Bruce [Head] had also made some overtures. Eventually it worked its way so that it ended up at Charlottetown, or whatever galleries wanted to pick it up. It was pretty straightforward. The galleries that picked up the travelling exhibitions – I wasn’t the only one there; Winston [Leathers], Bruce [Head], and Tony [Tascona] for the most part, there were other people there as well, but it was a small exhibition for travelling – we were well received by these particular galleries. In London, Ontario they bought a few things out of these exhibitions, so we were being featured in a sense. OB: A major ink work of yours, Evolution 10 Stage 1, was donated to the Winnipeg Art Gallery in April 1967 by George Aitken of McLaren Advertising. Can you tell us more about this? FM: I guess he liked it so much he donated it. OB: For a long time that was the only work of yours at the Winnipeg Art Gallery. FM: Yes, that was the only work. It showed once in awhile. They would put it up when they had other work displayed. It seems like it was a very popular piece. OB: More recently, the Winnipeg Art Gallery acquired a large group of your works. FM: Yes, actually about thirteen pieces. OB: These large-scale ink paintings of the mid to late ’60s to me look very different from the more expressive abstractions that you were doing in the early sixties and late fifties: larger surfaces of almost pure colour, though there are always minor variations of colour on them, these fit into an international context. There were the colour-field painters working in the United States, but also Jack Bush in Canada, and Ken Lochhead of the Regina Five, by then living here in Winnipeg. How much did you know about what these people were doing? FM: Well, you can’t help but notice them, particularly some of the painters in Ontario, Graham Coughtry, for instance, and Jack Bush. They were quite interesting, and I appreciated what they were doing. OB: You would have seen a wide variety of work in Winnipeg at the Winnipeg Shows because it was a juried exhibition and there were always very good artists on the jury (and critics). FM: Yes, by that time I was becoming aware of a lot of things. OB: Were you aware of Clement Greenberg coming to Winnipeg and doing some studio visits? FM: I remember him very well. OB: Did you meet him? FM: No, I didn’t meet him because we got a call from the Winnipeg Art Gallery and they were collecting works so that Clement Greenberg could have a look without having to move around to different studios. They collected the stuff and the artists had an opportunity to pick out whatever they wanted to show. The whole gist of it was that he had already been aware that things were happening at Emma Lake in Saskatchewan and so he was quite aware of some of the artists there: the Regina Five. He had already been there once. When he looked at the work at the art gallery, I don’t know, but I never got the impression that he was thrilled about what he saw, although he pointed out that he was favourable to Tony Tascona. He made a remark that, I don’t know whether he said that most of the other art was eclectic and I fell into that category. That was the only remark I ever heard from Clement Greenberg. I didn’t know it at the time, but Arthur Stevens – I mentioned him before – he was well-versed and he knew Clement Greenberg. When he visited New York on college business, he got to know Clement Greenberg a little bit. It didn’t mean anything to me at the time. I don’t know what remarks he did make on any specific works… OB: Because you weren’t there? FM: Yes, and I think it was kind of unfair in a sense. It seemed that that was a special response that the Winnipeg Art Gallery had to committees, the [Canada Council] Art Bank for instance, that were going around the country buying work for collections, for the Art Bank in Ottawa. I submitted some work because the Winnipeg Art Gallery sent us a note and said that the people from the Art Bank are coming in and they need some work to look at. So I took four or five works. What I got out of it was that obviously they didn’t like what they saw and the work was damaged. So at that point I said: “Well, that’s the last time you’ll ever see anything. I’m not interested” you know? If you submit your work, they should at least look after it. I don’t know who was responsible for the damage. OB: You showed at the Grant Gallery. Was that a solo show? FM: No, that wasn’t a solo show. I’ve never really had a solo show except for that Yellow Door Gallery show. Grant Marshall decided that he had the space in the lower part of his business, which was selling high-end furniture, Scandinavian stuff. Winston [Leathers] and Bruce [Head] had some discussions with him and they decided, “well look we can fix up the gallery, we don’t mind showing the work while you have furniture in it, it doesn’t matter.” So they decided that they would remodel his basement and call it the Grant Gallery [1959]. As a result, I was included on a sort of a piece to piece basis. I remember showing a fairly large work – I think it was about 5 by 7 [feet] – I did a triptych. At the time there was a sculptor who was hired by the art school, his name was John Daniel and he came from Texas. He loved the work so much he took it back with him. In effect, I gave it to him, which I’m prone to do at times. He went back to teaching in a small college in Texas. He was a very good friend of Don Reichert’s. Don, on his way to Mexico every winter, he’d be studying at one of the institutes there, the Allende. So, then they would stop by in Texas, so I would imagine the work is still there. OB: I see here also that you were shown in a number of galleries in Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal: the Pollock Gallery in Toronto, the Here and Now in Montreal, the Blue Barn Gallery in Ottawa, and the Dorothy Cameron Gallery in Toronto. Were these… FM: They were group shows. OB: Were they group shows of Winnipeg artists, or group shows in the gallery? Were these galleries representing you? Did they take your works on speculation and try to sell them? FM: Yes, we were new to the district, so these people wanted to show our work. It’s probably because they saw our work in some of these travelling exhibitions. Now the interesting thing was Dorothy Cameron, who in her own right was an artist. She liked my work and she asked me to send some, so I did. She sold one of my pieces. She wrote me a letter and said how much she liked the work. The piece she sold, a young collector wanted it, so he picked it up from her. Then I think she made an error in judgment, because she wrote: “Could you please send me more orangey red ones?” At that stage I just didn’t go for it. So, I wrote her back (not a terse note), but I told her that I wasn’t going to submit to her suggestion for some more orangey red ones. If I happened to have some well, okay that’s something else. I’m still that way for some reason… OB: You are also represented in the Bronfman Collection in Montreal. How did that come about? FM: The Bronfman Collection came out of the exhibition that we (with Winston and Bruce) had in Montreal. Tony at that particular time was already living in Montreal. He moved there because of his job. OB: Did he help organize this Montreal connection while he was there? FM: No. We actually did that. It was the exhibition that was at the Montreal Fine Arts Museum [Montreal Museum of Fine Arts]. It was a small gallery, called the Here and Now and we exhibited. It was funny the way they advertised it, because they changed all of the names except for mine into French. So, for instance Bruce’s name on the invitation was “Bruce Tête” and Winston’s was “Winston Cuir”. OB: You mentioned a couple of sales. Were you selling work in the nineteen sixties? FM: Yes I was. Because I was starting to associate with architects and doctors, and they always professed to be cultured, you know? I remember, there was one architect named MacDonald and he bought two of my pieces and he donated them to a new high school that was being built, Kildonan East Regional High school. They showed them to the library and they’re still there. There was one architectural group – Number Ten Architects . It’s changed hands. But the principals in that architecture firm bought quite a few pieces, but they’ve all moved. They never stuck around. One of the principals in that architectural firm was a guy named Al Waisman and the last I heard he was living and working in Vancouver as an architect and strangely enough, his habitation was a house on pontoons. OB: You won a competition to do a mural at the Windsor Library in Windsor Ontario in 1973. Was that executed? Did you do that mural? FM: Yes I did. It wasn’t a painting actually, it was a manufactured item. There was a display company that could handle the project. The pigment was sprayed on half-inch Plexiglas from the back. It was a fair size: and it was backlit, because at the time I was interested in that kind of a movement, something that would be really strong if it had light kind of penetrating it. This display company took my maquette and translated it into the size and the materials necessary. There was a whole bank of flourescent lights behind it. Once they had that feature, then they constructed the housing. There were small construction problems, but I was quite pleased with the whole thing. The whole fixture itself was about nine inches, ten inches deep and it was nine feet by fifteen feet. They got it in and installed it. We went down and had a look at that. From the main floor, if you went up the escalator, you suddenly came upon it. It was almost like an animation. This thing just confronted you. I thought it would be an interesting concept if people could actually see themselves becoming a part of it, entering right into the work. Being that it was an extracting, it still had relevance in terms of images that had partially human form, particularly the part that was mirrored. I could see the possibilities because when you are looking at a work and you have a chance to move around, you are not only moving yourself around, but you are moving the environment around. I found that was an interesting concept. OB: So, as you moved up the escalator, you would see this large backlit mural. You said it was a little bit like an animation because you were actually experiencing it in movement. FM: Exactly. A part of the imagery was a mirrored form, so anybody coming up there would see themselves in the mural. That was very deliberate – where you’d see it happen – because very often, even in peripheral vision, you see yourself in something. [A few years after the work was installed] a person came up there, we didn’t know it at the time, but he had a severe mental problem, and with nothing else but his own body, he destroyed the work. He smashed it. Bear in mind that the material was half-inch Plexiglas. He threw himself against it several times.The director of the Windsor Library wrote me a letter and told me all about this and asked me if I wanted to redo it and he suggested that I would go down and use the facilities that were close by in Windsor to have it redone. I was so taken by the fact that this disturbed individual had just shattered it, that I thought that the idea would [elicit] the same kind of attention. I didn’t want to have it redone. I think I was more concerned about the individual who did it. I just rejected the whole idea. So I gave them permission to seek out another solution. OB: What was their solution? FM: I don’t know. I’ve never been back. OB: What do you expect from a viewer to get from your work? How do you see the relationship between the kind of art that you make and the viewer? Because you’re not making a narrative, there is no story, there are no recognizable images. FM: But there is a title. You’ll find that in my monoprints there is a title. In a sense they’re enigmatic, but they’re still a part of the language. I see all these things as building a language; art is building a language. I think people should be able to look at something and relate it to their own experience without so much as labeling it you know, a ship on the sea or whatever. We just recently came back from London, England, and I sat in front of what must have been dozens of Turner paintings, and you didn’t need a title on the work to understand what it was. It was beautiful, just beautiful. Just the simple act of providing a sense of light, a reason for a colour to be there, that’s terrific. I’ve always been interested in that, since I’ve become aware of what it could do. OB: Is that one of the reasons you’ve privileged inks in your work? Because ink is a pretty transparent medium. FM: I’ve never made a sketch. When I start working I put out my materials and then I start working. OB: Do you base the paintings with gesso or something? FM: No. OB: What do you remember about the Winnipeg Show and your participation in that? What did those shows represent for you and your contemporaries at that time? FM: Well, it was an attempt to quell some of the dissatisfaction with the Winnipeg Art Gallery by the artists. Strange that it should come out that they invited people from across Canada to submit to the Winnipeg Show. It was still a good idea because at that time, of course, the University, the Art School itself, needed a boost anyway. The idea for a Winnipeg Show was formative at that time. OB: It also brought you in touch with and made you aware of what people were doing across Canada, who were modern artists. Did that at all surprise you, to see what was being done across Canada? Did it inspire you? FM: As Eckhardt said in that write up in the Ink Graphics catalogue of the show at the Winnipeg Art Gallery in 1962, the work is fundamentally more personal but not necessarily a study of other people’s work. I thought I had to do that, just my own personal thing. So I was kind of fantasizing, and the fantasies of course entered another era. One of the big problems when we left the art school was that those of us that wanted to continue on in printmaking at that particular time did not have a venue that we could go to without returning to the art school and paying a full year’s tuition just to use the equipment. The printmaking, which was what we were interested in, was controlled by all the classes that were arranged etc. So, there wasn’t that sort of freedom to go in and use the equipment and work. Eventually there was a group formed in the city: the Manitoba Printmakers Association. But to start with it was kind of pricey from my point of view. I wasn’t sure whether I wanted to put out the kind of money they wanted to rent space and get involved in it. So, when I discovered working with the inks in that graphic sense and with the particular imagery that I was interested in then I just let that slide by. Eventually, after years, I accepted the idea of joining the printmakers. Not in the real formal sense to begin with. People like Winston and Bruce urged me to go down there and they sort of gave me the idea that they were going to be working as well. In the end, it didn’t work out that way, and I was the one that stayed. From that point on, for the next nine or ten years, I was quite happy to do that. It really wasn’t in a printmaking sense and so I moved into the monoprints, which I found more satisfying. OB: But still using ink, which was associated with printmaking and eventually you produced many monotypes on paper. But you also began working with inks on hardboard: masonite and wood surfaces. Had you encountered that technique before? If I’m not mistaken, you used gesso on the wood boards as a base, and then you’d add your inks – organic inks, other types of inks – onto that. Can you tell us a bit about that technique? FM: It’s just experimentation really. When I first started using those inks I was working on very smooth paper, and I found that to be the most reliable. It just made me jump at the chance of doing work and that was important because at the time the CBC was starting to take up more of my time. But I found that in between projects there, I could do a fair amount of work. Then I moved a lot of it into a studio at home where I could spend a little more time developing the technique. OB: Could you describe the technique for us? Let’s take the work behind you, for example. FM: I started out with this bottom portion here [points to the ochre, brownish coloured point at bottom of work], which was the organic inks. I had already developed this shape. I wanted to extend it, but I wanted to use this other material. To me it was successful. I liked the idea of the two: the idea of having inks that were developed for the printing industry and the fact that as soon as the ink hit the surface it was practically dry. I had to work fast, and what it really helped me to develop was a sense of knowing what to do and knowing enough to stop. I didn’t want to continue once I had established…I don’t know really how it came about in terms of being able to make those kinds of decisions. That was really an unconscious thing. OB: Did you sketch anything out ahead of time? FM: I don’t sketch. I never have. I put out the material and I start working. What I do is all sort of intuitive in a sense. That’s probably the most interesting characterization of what that technique can do. I’ve seen people struggle painting with different media. I’ve struggled to. I could never come to grips with the fact that at that time materials took a long time to dry. Or they didn’t give you exactly what you wanted. I liked the ink because it is a transparent medium and that was really stunning in the sense that you could glaze very easily over it; you didn’t have to wait for it to dry. That it would be a medium that the paper would absorb a certain amount of and with the technique of wiping with various different types of material – not just cloth, but pieces of foam, etc. – it worked out very well. OB: Did you sometimes work with paper, and then glue the paper to the board? Sometimes with painting on gesso? FM: I sort of gave up the idea of using gesso too much. Where it did come in handy was when I started working on these larger pieces because of course the hardboard had to be sized. It wasn’t a technique that worked very well on canvas, so it had to be on hardboard. I think it proved itself, with the two or three layers sometimes of gesso, with a certain amount of refinement. Maybe a certain amount of sanding would give me what I wanted. OB: You mentioned earlier that the CBC was taking up more and more of your time. Eventually, the work that you did as a graphic designer at the CBC won you awards, among them the Anik Award for your animation of R. Murray Schafer’s Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima. Can you tell me a little bit more about the creative side of your work at CBC, and how that related to your practice as an artist in general? FM: When I joined the CBC it was more like an attempt at falling into the commercial area. That was my opinion of it, even the work itself demanded a certain amount of creativity. Just getting used to the idea of working for television was in itself a challenge. I believe that I was – in Winnipeg anyway – the first one that they hired as an apprentice. There were already two people in place at the time, Drope and Dave Strang. They gave me the designation as the apprentice because they were about to hire Bruce for the job. I was told that I had to go through the process. They felt that Bruce didn’t have to go through the process – he was already more advanced in terms of painting and stuff. So that’s where it all started. As an apprentice, I had to learn right from the ground up. For instance, the medium itself was in black and white, but I think as it was put that the creative artists – the stage people and stuff that go in front of a camera – have to be in a set that is conducive to them feeling good. Usually, the sets were painted in colour. Part of my job was to learn the equivalent in terms of the grey scale instead of the colour wheel. I had to prepare panels and have them calibrated. At the time, it was a job. The fact is that I took the job because I needed a job. Shirley and I had just been married, we’d already had a son, and so it was a necessity. So, I just kept going along with it, and I learned as I went along. The challenge in it was in meeting the requirements of the producers. That was an experiment without a doubt because of trying to transfer other people’s ideas to something that has to qualify in terms of reproduction and also the ideas. The project that you were talking about was really quite a challenge. To work with a composer, working with the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra, and the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra Choir was just an added challenge. That took a lot of time. Working with somebody else on a project – Dave Strang – meant that I had to kind of couple in with how he felt about things and then he had to do the same with me because I had different techniques that I wanted to try out. OB: Did you collaborate with him on the Threnody? That’s 1986? FM: Yes. It was a collaboration. Prior to that most of the work was hand drawing things and also committing myself to a lot of collaging and supplying the station with identification, supplying some illustrations and things like that for programming. OB: I noticed that in Threnody, a lot of the images had their origins in images manipulated through a photocopier. Was that a technique that you had been using for some time in 1986? FM: I had used it temporarily in developing some of the images that I had for on-air promotions. It kind of opened up the whole vista of things that you could do, not only in creating interesting backgrounds, but also introducing people to a kind of abstraction that just wasn’t hard edged or anything like that. It was interesting and I just kept on like that. I remember doing a whole series of these manipulations prior to doing the Threnody. I thought so well about them, I even submitted some. There is a photography club in the city of professional photographers, who demanded that anything that was used in their sphere would have to be done photographically and I thought to myself that “well, the photocopier is somehow related I might as well approach them and see,” but they wouldn’t accept it. I didn’t forget about it and when this project came along for Threnody, I just jumped at it. This was an absolutely dynamic way of representing. When you think about interpreting some of the elements in Murray Schafer’s work, it had to be abstracted, it had to be stretched out, and some of the images are really stretched out. The material that I used – they are for the most part recognizable. It’s Japanese people and also some of the anguish that they were going through. As far as I was concerned it was very exciting. OB: The Prix Anik Award jury felt the same way. FM: They did, because the jury at that time had other animations that were done on the computer. OB: So the digital age was just dawning at that time. FM: We thought we’d challenge it anyway. The producer was really excited about it. OB: I’ve noticed that you’re more than proficient with taking digital photos and certainly organizing them on a computer. Have you ever worked digitally as a designer, before or since your retirement at CBC? FM: I got involved with it because at the studio, work was being done. The studio itself bought a digital lab so to speak: computers and also the printing station and stuff. It was exciting. OB: It was a completely new way of working and you were already late in your career at that point. FM: Yes, and I couldn’t see a place for myself in that. For one thing, you had to have a pretty fair knowledge of photography and I was a klutz when it came to operating a camera, selecting f-stops and all this mathematical stuff. I just never got into it. I didn’t think it was necessary. Now digital means an entirely different thing. I remember, we were in Rome in ’94 or ’95 and we had never visited the Vatican. So, we decided to stop in and we saw all of these beautiful paintings and tapestries [in the Vatican Museums], and it went on and on. What really got me was that these paintings that were on the wall were being digitized. So, what you were seeing was a painting on the wall, but what you didn’t realize visually, was that it was actually a digital representation. OB: And that is when you started to realize maybe that the potential for good quality with digital imagery was greater than you had originally expected it to be? FM: Yes, it excited me, there is no doubt. If you can imagine it without thinking that this was a reproduction of the painting… OB: You used the techniques of collage, and of manipulated photocopies in your graphic design work at CBC, but as far as I can tell, you didn’t much use it in your fine art practice. Did you see your fine art practice and your design work as two very separate activities? FM: That is a very good way to put it. Primarily because the work that I was doing at the Corporation, it couldn’t include some of the ideas or some of the images that I would prefer to work with, which were in a sense fantasies. I did a whole range of collages with sports figures and stuff that came out of magazines, and because I knew how to manipulate ink, I could do collages without showing a lot of these torn edges or cut edges. They looked like oil type paintings and they were really well accepted. I could do a panel of collages of these figures and I broke down the inks and started to manipulate the whole thing, so that it became an entire amalgam. The camera would pan over them and necessarily…because if they were talking about basketball, they wanted to see somebody in that kind of situation, and so on. It was fantastic. I enjoyed it very much. OB: Now, at the same time, while you were actively exhibiting in travelling group shows, your works were being shown and acquired in Canada during the sixties and early seventies. After that, you seemed to have retreated from the art world. Can you tell us a little bit more about that? FM: Well, I was kind of thrown by several things. My imagery was not being accepted wholeheartedly. The architects kind of started to disappear from the city because they wanted to move to other places so that they could continue their own work. If you have a fairly large group of people doing the same thing, then it only stands to reason that somewhere along the line people are going to want to do their own thing and start their own careers. I can remember at the old Winnipeg School of Art that I loaned myself out as a model for the sculpture class and one of the strangest things was having invited all of these architectural students into the class who ended up just throwing clay at me. But then it all changed after that. They graduated and went into practice and believe me, Winnipeg wasn’t the big hubbub that it should have been – it’s just not big enough. Although, one architect designed and had a regional and secondary school built and he bought two of my works. OB: Also, I note that one of your works is in the collection of the Medical Faculty at the University of Manitoba: one of your large ink paintings. Many of the people who acquired your works were architects, so it seems that you appealed more to the architectural community here perhaps, or your work did? FM: I think that it’s probably true. They of course were probably the group that really thought about culture and the finer things I suppose. If you put up a doughnut, you kind of have to put something in it, you know? There were people that were certainly more successful than I was because all of my work was reasonably small. The other painters in the city were active in larger paintings. I don’t know where that idea came from, because I always liked small work. I continued to make art, mostly because prior to 1992 I was still active. But in a different sense: I was experimenting with several ideas. OB: What kind of work did you make during that period? FM: Well, I was doing monoprints with ink. But, as I mentioned, I had developed a technique in art school that I called “lift drawing.” It was similar to making prints, but drawings onto the reverse side of paper, laid down onto an ink lay-up, created not just line, you could manipulate the images. I got a big kick out of that, but I was still interested in doing work with ink, so I did some small pieces at home and that seemed to satisfy me at the time, helping to raise a family and all that. But then came some of these larger pieces that I was working with. I didn’t want to change the motion. OB: We are just talking about why you didn’t follow up on some of your ideas, like for example, showing works horizontally. Then there was a work that you produced in 1969, which had a metal construction emerging or attached to the painting, making it look like the pigments were actually flowing out of the painting onto the floor. Why didn’t you follow up on those ideas?. FM: Out of necessity. It involved a lot of labour. I didn’t have the money to carry on. But now that I look at it, it is a possibility, I haven’t forgotten it, but other things came up, like the work that I was doing currently. I think there is something to say for adding a dimension to painting, a different idea than an image that appears two-dimensionally by having the viewer think in terms of “hey, look, that’s coming out of the painting.” I thought that was an interesting idea, and perhaps one day I’ll do it. OB: What you did do is around 2000 you joined the Martha Street Studio, and you started working there. Can you tell us a bit about that and what that has meant for your art career since that time? You have had a number of exhibitions since then, you’ve produced many monotypes there, and you’ve had a good degree of success with these works -- success like you haven’t really had since the early nineteen seventies, and maybe a kind of sense of being a part of the art community in a real way. FM: I’ve never been so free. There is a freedom to it. All of the material was there; it was just a matter of doing the work. This is a carryover from what I was already doing, while I was working for the Corporation because I had to learn back there how to do things quickly, choice of image, and also the ability to say stop, stop the work, make a decision that the work is complete. That’s always come with me and I still think in those terms. I never sketch, so when I start working with these prints, it was a question of “here is a palette, start doing it.” It just kind of fell into place. The images came very intuitively. Up until this time I’ve been using a definition for some of these images, and it happened around the idea of memory. Describing how it’s related to memory I haven’t come to grips with that one yet, except I know that memory has a component that wants to get out; it wants to come out of your being. I am willing to accept the images that come out. I think there is nothing more important than being able to start a work and finish it and being able to say that that’s the piece; that’s the memory. Working at the print shop was just phenomenal. I was captured by the number of people who were working there and they were working in a traditional sense. After a while, they were looking over my shoulder, they were looking over each other’s shoulders, and as a result, there was a terrific exuberance, people making art; printmaking. I was really happy then, no doubt about that. OB: When was the last time before that, that you’d had a sense of being part of a community of artists? FM: That never really appealed to me too much because everybody seemed to be striving towards a concept that I thought about, that is, the pyramid. And if you look at the top of the pyramid, how many people can stand on top of a pyramid? I just assumed that if you have a couple of people who are doing work that needed to be at the top of the pyramid, it just cuts everyone out from becoming excited by that sort of thing. Up until this time I’ve never thought about standing on top, but if I was to do that, I’d rather go down to the places where pyramids were entirely different; they’d have a lot of room on top. The Incas for instance, and all those cultures in South America and Mexico. Interesting idea, I should really put it out there sometime. OB: You developed friendships with people at Martha Street, for example, Sheila Spence. I know that she included a photographic portrait of you in her recent [2009] exhibition at the Winnipeg Art Gallery. Were there other artists, most of whom would have been younger than yourself, who you would like to name as people that you struck up friendships with? FM: Well, right off the bat there was a person who was teaching there, as well as making prints: Sue Gordon. She still works in the industry, and then there were several others who were a major influence sometimes in doing work. Not that I ever changed my mind about the images that I wanted. Just being around them, just being that they were good artists and really doing their own thing. OB: You mentioned imagery before. One thing we haven’t spoken about is this whole series of black and white prints, which are laden with images, specifically with outlines of female bodies. When did that series of works begin and when did you get the idea for that? FM: Well, if you recall some of the images on that mural, they were… OB: Anthropomorphic. FM: Yes, and there was promotional work that I was doing at the CBC that included those kinds of images. So I had a project to do a promotion for the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, and it turned out very successfully. It too got an award. So, it wasn’t that people weren’t accepting what I was doing, but it seemed like that, well, it was really kind of a minor thing… As far as these drawings were concerned, I got interested in a kind of freedom in drawing. OB: So they were drawings not prints? FM: Yes. Eventually I turned a series into some lithographs. OB: Some of the drawings were transferred into lithographs? Did you start doing those at Martha Street, or before? Because you mention the mural, which is the nineteen seventies, Martha Street is about two thousand and onwards. FM: I didn’t start it at Martha Street, and some of the images I do there, they’re not in the same context. To me they’re very abstract. OB: Which is what most of your monotypes are, although you always used the word image to refer to them. Do you work from imagery? You mentioned that you worked from memory. Memory is an important element. Yet they are abstract forms. FM: I mentioned a theme of memory. Realizing that there are several people who are trying to describe how people need a process that they can somehow exercise – a catharsis to kind of regenerate the kinds of feelings that you have within you – I’m referring particularly to C. J. Jung… that sort of woke up in me the impression that whatever I have I can generate, and I don’t have to describe that. Through imagery I can. OB: It was a way of communicating those feelings? FM: I understand it as another language. I like to think of it as another language. Not that I deliberately stopped making sort of recognizable images. But this way I find is the most satisfying. OB: Bruce Head passed away a couple of weeks ago, and Winston Leathers a couple of years ago. These were people who were your friends, your colleagues, and your associates. Can you tell me a little bit more about the artistic community that you lived in, with them, with others? FM: Well, I was always willing to become a sort of a member of the group. In my experience though, it never really did come off that much. For instance, if you want to say the Regina Five, or Painters Eleven in the east, and people like that in groups. In fact, they could just as easily start an art school. Wouldn’t it be nice to have a plethora of art schools, or an individual can make a choice and say: “oh, I’d like to be a part of that.” OB: Some people talk about the “Four Musketeers,” Tony Tascona, Winston Leathers, Bruce Head, and Frank Mikuska. FM: Yes, and as far as I was concerned, I was always the add-on. Those three individuals always gave me the impression that they had the really big urge to…they were very ambitious painters. A few of them were more experimental, but on the whole, I couldn’t understand why they weren’t interested in opening up, and exploring differences. I have a few favourites coming out of the American scene -- Robert Rauschenberg – I loved some of the images that he was experimenting with, especially using Plexiglas and things like that. The images were not drawings but he accepted these things as being elements that he could use in his work. They never thought about those kinds of things. So, I was somewhere out in left field as far as they were concerned. They brought me along, because obviously some of what I was doing was interesting to people. There were reviews whenever we had an exhibition and the reviews were always favourable towards me. So, I guess in a sense, I wasn’t part of the group. I was an individual, and they were individuals, and we fought sometimes. But, for the most part, whenever it came about in public, I was part of their little group. I’m still trying to understand why. Because, I was in a sense very demanding in terms of being able to describe “why are we making art?” or “why are you doing it that way?” Some people have a very good idea of why they’re doing it that way. I don’t. I just do it. That’s probably the way I’ll be from now on. Tony if you look at his background from the early days – from when he started out – always had the idea that he was going to be an artist. It was difficult for him; it was difficult for most of us at that time. Hell, we were just coming out of the fact that we were born during the Depression and that sort of thing. Times were tough. Tony had more of an ambition than the others. The other Musketeers weren’t exactly tied in the way he was. He had the ability to relate the idea of being an artist to people who were willing to accept him on a different level. I think he proved his point. He had better social skills than perhaps any of the rest of us, and because he very often related the fact that he had a rough time of getting to the point where he was. People accepted that. That’s a human factor. He had a lot of willpower. I think everything that he tried to achieve was done because he felt that way. In a sense, he looked at the situation and looked at other people’s work and said: “I can do that, I can do better than that.” I can hear him saying that today. One of these days, it will be recognized. It’s quite a concept, being recognized, but for what? The background that you’ve come from, or the work that you’ve done or are doing or just an idea of being a person? I don’t know what it is. It’s hard to describe. But he did what he wanted to do and probably gained a fair amount of success in terms of people understanding where he was coming from, which is a very difficult thing to do. I don’t think he ever wanted anybody feeling really sorry for him. He was taking advantage of the materials that came along to him and he put it into his work, so there is a lot to be said for that. OB: Winston Leathers was also pretty experimental with techniques. He was experimenting with printmaking techniques and photography and other things. Did you have a feeling of affinity with Winston’s work? FM: I have an affinity for art period. I think he was more of a teacher. He did teach at the University… OB: The Faculty of Architecture for many decades. FM: He was really interested in people and development. His work was very private. The rest of it I’m not sure about. Here I am getting myself into a corner that I can’t explain, except that you know, I’d like to continue working because I still have some ideas that I want… It is a pity that both Tony and Winston, and now Bruce have passed on and it sort of concerns me, because I have no intention of trying to underscore… it’s a pity because I think they still had some work to do. Whenever I think about what influenced me really, it was one particular individual at the Art School, Robert Gadbois. This man had enough intensity in him that he could draw you a scenario that you may not have understood at that particular time, but then it hit you when you started doing your work. So, I’m really glad that I got caught up in this world of art and artists and that it’s a significant way of making a contribution. OB: Thank you for your time, Frank. DONOR RECOGNITION SERIES The Frank Mikuska Donation is the second in a series of three shows in 2010 intended to acknowledge and to celebrate the important contribution of private donors, not only to the permanent collection of Gallery One One One, but also to the School of Art and the University of Manitoba. Following The Frank Mikuska Donation exhibition will be a show of works selected from a donation by Winnipeg collectors Anna and Lyle Silverman, opening in May. Gallery One One One hours are: Noon to 4:00 PM closed weekends. Admission is free. Gallery One One One is located at the School of Art, Main Floor, FitzGerald Building, University of Manitoba Fort Garry campus, Winnipeg, MB, CANADA R3T 2N2 TEL:204 474-9322 FAX:474-7605. The FitzGerald Building is located at the University of Manitoba's Fort Garry Campus next to the University Centre. Parking is available in the Parkade behind FitzGerald Building, and at meter and ticket dispenser lots. Parking is free after 4:30 PM and on weekends. Campus map link. For information please contact Robert Epp eppr@ms.umanitoba.ca |