ANDREW FORSTER

[First published as a review in Vanguard magazine, Summer 1986, volume 15, number 3, 40-41.]

Andrew Forster does not always feel he should be himself. He can just as easily be other artists if he likes, so he inserts his name in the biographies of well-known Canadian artists and posts them on a wall at Eye Level Gallery. In these biographies, we can recognize the lives of Garry Kennedy, Liz Magor, Alex Colville, Michael Snow, and others. Accompanying the exhibition is a slick and thick catalogue that features a most ambitious borrowed biography -- that of the contemporary European artist Jannis Kounellis.

Actually, it is not a biography as such but a reprint of a catalogue text by Rudi Fuchs, the Mary Kay cosmetician of the last Documenta, in which Forster has substituted his name for that of the original subject of the piece, Jannis Kounellis. Forster also substitutes certain of the catalogue's photographs for others of is own choosing. The result is a piece of satire and an eccentric voyage into Forster's own increasingly complicated personal mythology.

Kounellis is a shrewd choice. As an artist whio has been consistently admired throughout the last few cataclysmic years, Kounellis might be called a "cross-over" artist -- one whose work spans the most rigorous conceptual and performance strategies (like exhibiting live horses) and the most characteristically post-modernist (i.e. the classical statuary he sandwiches into his assemblages). Perhaps Forster chose Kounellis not only for the convenience of the Fuchs essay, but also as a way of situating his own work at the point of transition of new and old sensibilities.

But we are suspicious of "shrewdness" in artists; shrewdness too often means a canny career move, a cynical use of techniques of appropriation, and an uncomplicated dishonesty. Several of Forster's teachers at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, most notably Robin Peck and Garry Kennedy, regard certain kinds of dishonesty as artistic tools or material -- things that facilitate the effective manipulation of other materials, such as the art press, the audience, or dealers.

But Forster's interest in appropriating other artists' biographical data and art deserves to be given the benefit of the doubt. He seems always to work in a straightforwardly public way with his material. His practice seems well within the "fair-use" tradition of quotation -- even in his use of complete Otto Rogers images in a previous exhibition.

In his first exhibition, Andrew Forster (1942- ) Retrospective, Forster imitated, made-up, made-over and mythified himself. In this "retrospective" Forster worked out a pastiche of real and imagined works, dates, and places. Forster's "real" work (a provisional term), his sculpture, and written piecesof the previous few years, had a minimalist or conceptual nature. It was easy to imagine them matching the spurious dates he made up for them in the catalogue.

In his 1983 exhibition, Forster constructed a fictional artistic personality for himself. His catalogue was central to the exhibition. The show consisted of cards on the gallery wall that named the works, but the works to which they referred were not in the gallery. Instead the catalogue contained photographs of the work and a brief, fictional chronology of Forster's life and work. It also contained an interview with the artist.

The 1983 catalogue was dedicated to Elmyr de Hory, the famous art forger, and for those who know Forster personally -- as many in Halifax's tightly-knit art community do -- the catalogue's mis-information was transparent: an inside joke.

For example, in the 1983 catalogue Forster gave his birthdate as 1942, when his actual birthdate is probably closer to 1952 or even 1962. Works that he listed as being first shown in 1966 (i.e. his monument to Giacometti) Haligonians know to have been made between 1980-83. In the catalogue photograph of the "Giacometti" piece, only little clues like the contemporary lighting fixtures proved that the piece was not made in 1966, as stated in the catalogue.

In the present exhibition, Forster presents a much more complicated set of variables, for the show by no means stops at appropriation of the Fuchs/Kounellis catalogue. Forster is not just dabbling in the ephemera of artist's lives, i.e. the stuff that gets published, gets shown, and gets made. The way Canadian comics make a living by imitating American media figures is not an apt analogy to Forster's project. Much of the power of his work has to do with the poetic character of his substitutions and the ease with which layers can be distinguished from each other.

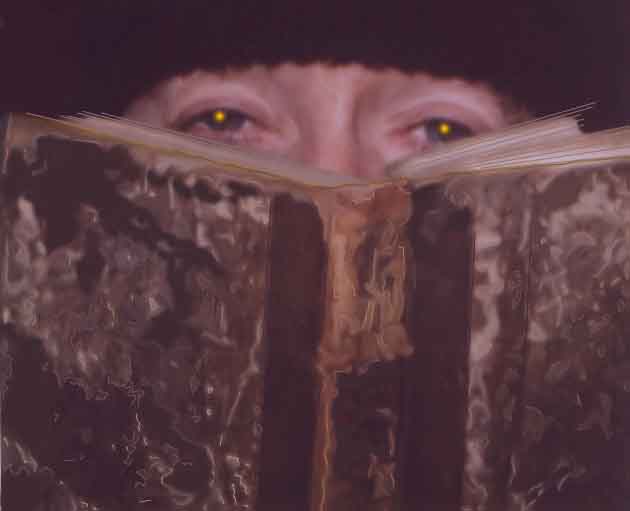

Everywhere, his name appears like a code word. His appropriated catalogue substitutes pictures -- of spoons, handles, mechanical-looking things, landscapes of the pyramids, blurred photos of a painting and a spectator in a museum, the Statue of Liberty, boxing gloves on truncated arms -- for the pictures that originally appeared. The photos are puzzling, personal, and evocative of the nineteenth century, none more so than those of the Crystal Palace and an elegant ink-on-canvas version of the original sketch for the showplace.

The inclusion of photos of national monuments of the last century and various mechanical parts highlights what is glossed over in the flowery rhetoric of Fuch's original words and photos, like the sketch of Rimbaud playing a harp and Courbet's nude. Perhaps we are meant to pose questions about the continuing industrial basis of Romanticism.

Like Fuchs, but with distance, Forster addresses a version of the Romantic artist and Satanic mills. But unlike Fuchs and other neo-Romantics, Forster is able to slip in and out of his own place in the art tradition by being other people and reveling in the discontinuity of it all. Like a ghost he is out of the fray, he can be his own invisible self -- or so it would seem. Forster ventures into commentary as art the way a logician envelopes one system within another as a temporary, pyramid-building way out of an insoluble problem. The insoluble problem for Forster -- as for Duchamp and a thousand others -- is how, at once, to be and not be an artist; how to deny and simultaneously glory in a privileged position.

|

|