[First published as "On Temples, Trials and Taste: Paintings by John Wayne Gacy" in Mix Magazine, 22/3, 61.]

The press release announced that the show would open in late October to kick off the new Plug In Inc. space in Winnipeg's Exchange District. Experienced curators usually play the press like a violin on such occasions, but sometimes a simple press release can escape everyone's predictions about public response. The show, called "The Moral Imagination," was to include works by several artists--many from Winnipeg-- and paintings by the executed American serial killer John Wayne Gacy.

The curator is Wayne Bearwaldt, who works full time for Plug In. He has done controversial shows before, but this one sparked an immediate and furious public debate before it even happened (in fact, as I write it hasn't happened yet). Plug In produces and hosts many uncontroversial exhibitions, too, and so the vindictiveness of the public attacks on the gallery by talk radio and the tabloid press was surprising: many people demanded that Plug In--a gallery which has existed for over twenty years--be shut down. In an nutshell, Baerwaldt and Plug In were accused of showing support for a mass murderer by showing a mass murderer's paintings. This position is, of course, unreasonable, but the emotionalism of the attack put the Winnipeg art scene into a moral panic. Some of the artists slated to appear in the "Moral Imagination" considered withdrawing their work, and others actually did so. Many participating artists recognized that they were caught in a complex position in which a publicity fire storm could completely overshadow their art. A few had objections to the show which scarcely differed from those of the tabloid press.

Unlike, say, a Robert Mapplethorpe SM photograph, Gacy's images are innocuous-- circus pictures, mostly. In a stirring example of tabloid hypocrisy, The Winnipeg Sun reproduced one of the Gacy paintings on its 17 September front page while in the same issue demanding that the paintings not be shown publicly.

Obviously, Gacy is not an artist of the caliber of a Picasso, who was a wife abuser, or a Caravaggio, who was a murderer, or a Francis Bacon, who was a thief and a prostitute. Nevertheless, the mediocrity of the Gacy paintings became a red herring which many people swallowed whole. Gacy's art highlights moral issues in vernacular, folk and outsider art very well, as art made by other untrained artists, including other criminals could have also done. The issue of how the sensationalism of John Wayne Gacy's crimes might twist the entire exhibition's thesis can be taken up with the curator, but one cannot dismiss Gacy's outsider art simply because it is "bad" painting. The tabloids had no space or inclination to discuss art history, how since Gauguin "high" artists have been influenced by vernacular, folk and so-called "primitive" art. Neither was the press interested, obviously, in how contemporary curators like Baerwaldt study work made across class and academic lines in order to get new perspectives on all art, high and low. They simply bayed for blood

No "excuses" are needed to show the Gacy work, and so the lessons this controversy offers are not about how parallel galleries should write press releases. This exhibition was not, could not, and should not have been "finessed" in publicity. Tough exhibitions cannot be spin-doctered into nice exhibitions. However, today's climate of public thinking about the nature of art galleries is worth pondering. The Gacy controversy highlights the difference between the idea of the public art gallery as a temple in which worthy art should be almost worshipped, and the idea that an art gallery as a place to make judgments, almost as if the art were on trial and the gallery were a court room.

These two competing models fairly describe Winnipeg's Gacy controversy in broader terms. Anything and anyone can enter a courtroom, after all, but only a select few can enter a temple. (We should note that the political right in North America has a deep reverence for temples.) The idea that our public galleries are somehow "inaccessible" is congruent with common ideas about the inaccessibility of sacred space. If the gallery were a temple, so goes the thinking, then one should enter it--if at all--in order to venerate objects. By contrast, if the gallery is considered to be like a courtroom, an object must be viewed dispassionately. Unclean things should not be kept outside the courtroom of art, where a viewer is judge and jury and little is sacred.

Like everyone involved in this controversy, including Plug In, victims' groups used the Gacy paintings to make a point, and to get publicity. The paintings reminded the victims' rights people of abuse; they are unpleasant because a mass-murderer made them; the gallery (temple) is somehow honouring Gacy by showing his work; the attention the paintings get inhibits a victim's "healing" process. As one victims' rights person put it "the same hands that killed 33 young boys made these paintings." The belief that evil spirits inhabit paintings is consistent with the belief that an art gallery is a sacred space. (Ironically, art world insiders seem to take art galleries far less seriously than the outsiders, who in their expressions of hatred for Plug In were defending the sanctity of art, the nobility of good artists and the glory of having a public exhibition.)

One of the victim's rights representatives at a Plug In public meeting felt that it would be OK to show the Gacy paintings in Manitoba's Stony Mountain Penitentiary. I understood the logic, but not the intelligence, of this idea. Taking the Gacy paintings out of the "Moral Imagination" show would be to serious compromise a curatorial idea. All art galleries adhere to a simple principle that the art discussed in a catalogue or a press release must actually be seen, but for the temple people (notice how closely the temple resembles a museum) art is merely deposited and maintained because it is valuable, like money in a bank.

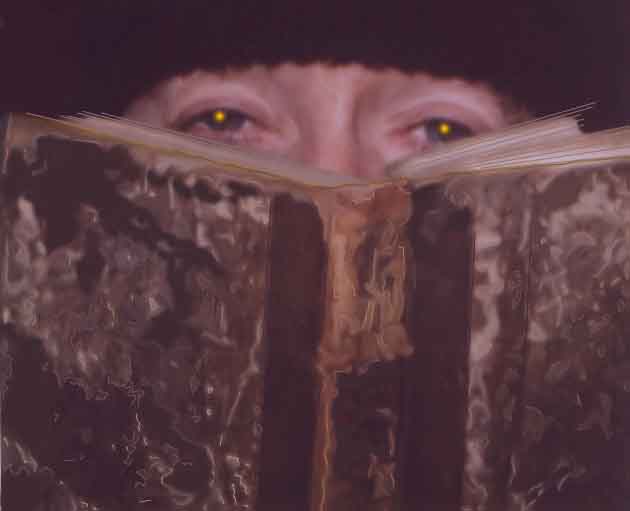

Instead of believing that evil lurks in the Gacy paintings, why not admit that what is really fascinating about them is our compulsion to project fantasies on inert matter? These fantasies need analysis, and that is what it was proposed they would get in the "Moral Imagination" show. We have yet to see whether that analysis will be permitted to happen.

|

|