E.J. (TED) HOWORTH

Essential Journeys IC03 Gallery, University of Winnipeg

[First published as "Long John Printer," in Winnipeg's Border Crossings,Winter, 1998, 53-54.]

Only soft-coated, soulful-eyed mammals thrive in the forests of today's commercial wildlife art. These beasts tend to denude the animal art ecosystem of all expressions except cheap sentimentality.

Wildlife art needs more than cuddly carnivores to survive. By referring to E.J. (Ted) Howorth as a "wildlife artist"--even if both he and most wildlife artists might reject the designation--I hope to encourage complexity within wildlife art's increasingly one-note biomass.

The differences between Howorth and today's commercial animal artists may be plain, but so are the differences between his art and the ironic, postmodernist neo-avant-garde production that currently dominates the art world. Howorth's work is more complex than commercial animal art but without the irony and ambition that characterizes much contemporary neo-avant-garde art.

This artist encourages artistic biodiversity in two important ways: firstly by spicing up animal imagery with imagery of tourism, the city, humanity and architecture; and secondly by garnishing his imagery by means of various technical manipulations.

The work could have been edited--or "styled" as hip curators like to say--toward a more consistent show. "Essential Journeys" seems to me to be an all-purpose name that allows the artist to include just about anything in this exhibition. Pelicans, reptiles, sandpipers, water lilies and the odd turtle, fly, float or crawl across the works, but a few spanners in the works--a kitsch pirate lamp most importantly--make appearances, too.

The pirate lamp is featured in several variations and in reproduction on the exhibition brochure. It introduces a little visual subplot about split images and hallucinogenic light into the exhibition. The pirate can also be read as a characterization of rapacious human intervention in the natural world. Howorth supplements the pirate with images of tourists and holiday islanders in tropical settings.

I read Howorth's play with a motif of artificial illumination in terms of an opposition between the natural and technical that seems to run through this show. The artist does impressionism by putting atmospheric static around some of his representational figures. Coloured squares of computer "pixelization" festoon the birds of Howorth's "Questing Travellers" series. The computerized look must be deliberate, since current technologies can render smoothly photographic surfaces easily if an artist wants it. Some images are rendered as if one were looking through a multicoloured screen at something which has not been itself been structurally distorted.

The most ancient and modern technical means are used to make this work, including photography, freehand drawing, computer scanning, engraving, etching, lino and screen printing, and so on. On one level, this show is an inventory of printmaking techniques. Howorth makes almost nothing but prints, and he teaches printmaking at an art school, and so his work is a good standard against which to judge the the ancient arts of reproduction against the multimedia tools which both he and the typical wildlife artist use to different ends.

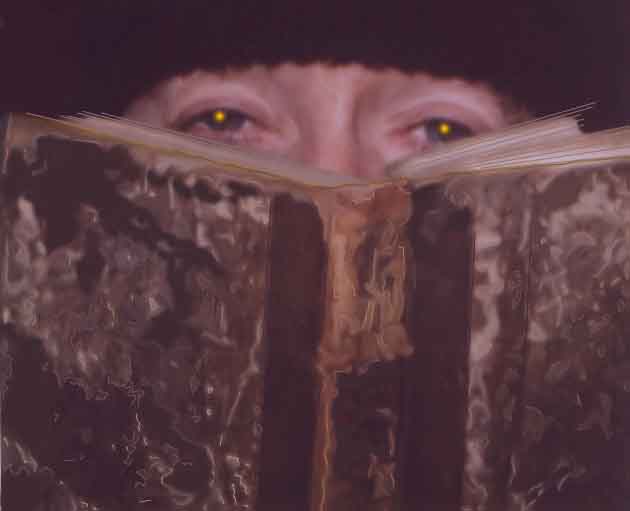

Howorth hones the many time-honoured artistic and economic practices of the traditional printmaker to contemporary use while many wildlife artists simply bilk a naive public by selling offset reproductions as fine art prints. Howorth, like all traditional printmakers, produces sets of limited, numbered editions in which each impression, as the edition number grows, changes slightly because of, for example, the wear on the stencil used in the screenprint. The degradation of a screen printing stencil in Howorth's "Mental Migration" print, for example, would be undetectable in early impressions, but as the edition gets larger, the prints get fuzzier, and so the artist limits their number. The person who acquires Howorth's screenprint "Sarah in Cuba" is buying a rare thing, something completely unlike the typical wildlife art print which is an offset reproduction no different from the reproductions in this magazine.

When Howorth uses a new technical means such as computerization, (which of course has affected every contemporary means of reproduction) he is careful, as mentioned, to make that use obvious. He highlights the technical means which other wildlife artists are at pains to hide. What is not obvious is identified to the non-technical viewer in wall labels. But I question both the cult of the limited edition print to which Howorth obviously subscribes as much as I do the equivocations of printmaking traditions that one sees in the wildlife art industry. Obviously I favour Howorth's transparent use of media and marketing. However, the signing of any object as art--unique or multiple--has been an ambiguous gesture for some time. The more copies of an object that are signed, the less expensive each one should--theoretically at least--become. But there are no consistent rules about the art market values of prints, reproductions, or unique art works, just vagaries of exchange value. I attack wildlife art because of the obfuscation around its market, but making those issues clear will not necessarily make traditional printmaking any more valuable or less archaic.

|

|