HAROLD KLUNDER

[First published as a curatorial essay in a catalogue for the Art Gallery of Newfoundland & Labrador in 1999.]

Harold Klunder was born in the Netherlands in 1943 and immigrated to Canada with his parents in 1952. He has lived for many years in Flesherton, a small Ontario town. Recently he bought a tiny house in Newfoundland -- he is growing a relationship with the Rock.

I met with Klunder for the first time a few years ago in Corner Brook, Newfoundland. Later I visited him in Lethbridge, Alberta. My view into his studio practice is peculiar because I often see him in exotic student digs, so I may have developed a slightly distorted, perhaps romanticized, view of Klunder's roving life as a full time painter and a part time teacher. I once saw him playing a strange stringed instrument as he assisted his wife Catherine in a Lethbridge performance work. That made me think of Klunder as one of Canada's true artistic bohemians -- a kind of wandering artistic minstrel -- like Rita McKeough, Michael Fernandes and Collette Urban.

Performance is a sideline: Klunder is primarily a painter and a print maker. Years ago Klunder made abstract geometric paintings. (We have not included any of these works in this exhibition.) In the 1980s and 1990s Klunder began to make thickly-painted works that echo the Dutch tradition of organic, impasto painting: Rembrandt, Van Gogh, de Kooning, and Karel Appel spring to mind. Because Rembrandt and Van Gogh are icons of artistic value in popular culture, I venture that Klunder regards them within a big picture of world art and not in narrowly ethnic terms. These artistic giants do figure in Klunder's heritage, however, the way Michelangelo can still lurk in the thoughts of an Italian sculptor, whether or not they carve marble.

Klunder's painterly Dutchness seems plain to me. It is an immigrant's Dutchness. The immigrant artist paints his roots in broad, legible and historical terms. Like Monica Tap, a Dutch-Canadian painter of multi-layered Baroque landscapes, I'll bet Klunder's painting is more ethnically "Dutch" than most contemporary Dutch art, given the internationalist and multimedia oriented Dutch art that I've seen.

Klunder, like many painters, is, as I have mentioned, also a musician, and he has painted tributes to Schoenberg. His painterly improvisation has been compared to music and he makes musical analogies himself, but I think this comparison has limits. Music's relation to abstract painting has been mined out. The act of painting and the act of music making can be displays of manual dexterity, jazz can be compared to Pollock, and Whistler can call his paintings "symphonies." But once one allows abstract painting a little independence the musical paradigms seem unnecessary.

I saw a travelling Klunder exhibition in Markham, Ontario last year called Love Comes and Goes again curated by Brian Meehan (and first shown at the Tom Thomson Memorial Gallery in Owen Sound). I was deeply moved by the paintings, and by how they looked in a spanking-new art gallery. As I contemplated Klunder in that pristine environment, I felt that that the experience of his paintings signaled the close, at least for me, of a certain intellectual contest about visuality and painting that had nagged me for years. (This realization made me a bit giddy.)

Martin Jay's book Downcast Eyes, the denigration of vision in Twentieth-Century French Thought sums up contemporary cultural theory's mistrust of visuality and the intellectual enjoyment of things like Harold Klunder paintings. French writers got the anti-visuality movement going, Jay relates, and by the 1980s academies everywhere -- especially English departments -- had become bloated with what he calls critiques of "ocularcentrism" :

"By 1990, Fredric Jameson could effortlessly invoke its [i.e. the French anti-visual discourse's] full authority in the opening words of his Signatures of the Visible: 'The visible is essentially pornographic, which is to say that it has its end in rapt, mindless fascination...' " [Martin Jay, Berkeley: University of California Press 1994, p.589. His quotation is from Fredric Jameson's Signatures of the Visible, London, 1990, 1]

What plays well to intellectuals can, of course, play poorly to painters, art patrons and dealers. Despite "theory" wishing it away, we remember, a painting revival that began in the neo-expressionist 1980s continues to thrive, and Klunder is part of it. Given this success, one wonders whether the critical rejection by theorists is essential to the popular success of an art movement, and whether, for example, the critical association of visuality with pornography makes painting all the more enticing to viewers.

I oppose vision-hating intellectuals, but a simple dismissal of these critiques is as unsatisfying to me as uncritical acceptance. A Klunder painting is not an argument for anything, but merely evidence for a riposte. I'll say this much: painters should be discouraged from being anti-intellectuals, even if some intellectuals don't like what they do. It may be tiresome that pleasure has always been pornography to a certain priestly, iconoclastic caste (all pleasures are guilty pleasures to some people), but attacks by iconoclasts can be good for painting practice. They build help solidarity and an audience.

In any case, I'm beginning to believe that anti-ocularcentrist theories really are dead. Klunder's painting has helped me to look again and think again about art in a register distant from the "downcast eyes" of French theory, the cynicism of literary critics and other unfelt responses to complex, intuitively-made art. But my responses, I remind myself, are as intellectual as they are felt. While evaluating older ways of looking at Klunder's work and casting around for new ones, I simply take into account that a vision as broad as Klunder's is bigger than the text that tries to span it.

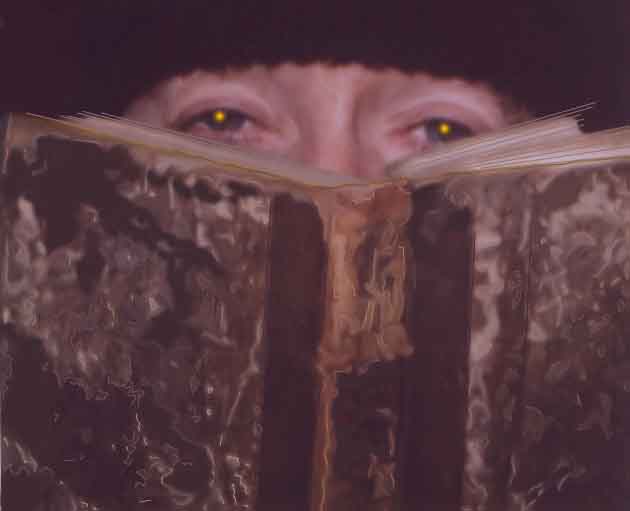

Klunder's recent paintings are layered, crusty, variegated and rich. He scumbles gobs of paint over paint. The work is full of active organic forms. At first the completed works look spontaneous, as if the paint has been just been furiously slathered on, but a deeper look reveals the complexity and variety of the improvisational marks that allow us a peek through the top layers.

"Beginning in the early 1980s, Klunder's paintings coalesced as a grotesquery by the end of the decade and continues in this fashion - hardly the rarefied air of abstraction being refined to some ground zero, but being brutally honest about the nature of painting." - Ihor Holubizky Love Comes and Goes Again, Owen Sound: Tom Thomson Memorial Art Gallery 1996 p.10

Klunder has been around long enough to have seen several phases of abstract painting come and go. He has seen Greenberg's tasteful opticality, Stella's minimalism, and many post-war geometric and expressionist revivals enrich the tradition of abstract painting. Last year Peter Dykhuis and I curated an exhibition called Monitor Goo as a way of assessing recent abstract art. Monitor Goo included works by young graduates of the Nova Scotia College of Art & Design and paintings by senior artists from Winnipeg. Even if a wide public is still as hostile to abstract art as they were in the 1950s, today's young abstract painters treat their work almost as if it were popular culture. They get their ideas from television and computer graphics, and their paintings only superficially resemble previous abstract paintings.

Young abstract painters have no patience for the old fights between "abstract" and "representational" painting, and neither is Klunder an abstract purist. Expressionistic heads occasionally poke out of abstract surfaces in Klunder's works. Like the younger painters, he ignores orthodoxies of abstraction: "I am influenced by everything; what I find on the street, what I see in stores, on TV, etc. I love the look of things and what the look hides. I love the idiosyncratic, the boring, banal everyday stuff, the things that fill our every moment, moment-to-moment...everything at once all the time..." - 30 March 1998 letter to the author, 1-2.

"Painting is a no-holds barred endeavor for Harold Klunder, unyielding in its declaration of materials and visceral presence. Far from being exhausted or relegated to another period piece of art history, he also leads us to an understanding of the modernist condition, with a vital and purposeful present." - Ihor Holubizky Love Comes and Goes Again Owen Sound: Tom Thomson Memorial Art Gallery 1996 p.7

Klunder's early 1970s prints have a placid quality suited to those minimalist times. A group of 1972 black and white monoprints in this exhibition contain calm, restful patterns and lazy, fluid lines. By the late 1970s the prints became expressionistic -- quickly produced records of emotional release. The occasional biomorphic figure -- for example in "Elderslie" (1979) -- begins to poke its head out of a print's black ground. More recent prints, like the paintings, convey an explosive expressionism that is complicated -- even contradicted -- by the less immediate apprehension of a technically complex, richly layered and beautifully unpredictable surface. In the paintings, the paint appears to have been applied slowly, as if it were dragged and not slapped over the underpainting, and in the prints, the expressive mark on the surface is often the end of an intricate process.

Of the many narratives that can be imagined about Klunder's prints and paintings (his geometric abstract paintings and prints, for example, excluded from this exhibition, encourage other narratives) the story of an evolving emotional and technical complexity is the most compelling and straightforward.

|

|