David Merritt, Anna Leonowens Gallery

January 31 to February 4, 1983

[This piece was first published in Vancouver's Vanguard magazine, May 1983, 31.]

David Merritt's installations are tightly structured and cleanly presented. He admits that "the presentation can eclipse the work itself," but feels that the quality of the idea should somehow be matched by the technical quality of the work. The work must be clearly presented in spite of trite readings that might greet a well-packaged show.

In his most recent exhibition at Halifax's Anna Leonowens Gallery, Merritt arranged a few carefully chosen components in strict symmetry. A large photo-mural of a view of the Atlantic filled the end wall of the gallery. Two small ink drawings and two large photo reproductions of architectural reliefs faced each other from walls that flanked the photo-mural. Several readings could be developed from the scheme, all related to the history of representations of labour and landscape in the Maritimes.

The original stone reliefs grace the facade of a vocational school in Halifax. They could be clearly seen in a photograph of the building that was showcased in the front door of the gallery as an introduction to the show. The reproductions were hung at the same height as the original reliefs and approximate their scale. One relief depicts a classicized version of fishermen hauling up a net by hand. Its mate shows miners in the same idealized manner. The reliefs date from 1948 (when the school was constructed) and such representations of grim-faced, heroically built workers are common enough, although this kind of pious depiction of the dignity of work is lost to many contemporary viewers. Nevertheless, Merritt's reproductions of the plaques were seen by some gallery visitors as straightforward glorifications of Nova Scotia labour. A more complex reading engaged them as self-consciously appropriated images which used the debased rhetoric of social realist art to illustrate the disjuncture between representations of labour and the present day realities of labour. The irony at work here involved an outdated or bogus representation in a parody of itself.

The title of the show, Imagining Life Below and Beyond the Horizon referred to the occupations of mining and fishing on the vocational school reliefs. An allusion to the use of the horizon in Romantic and popular art as a nostalgic symbol was also obvious. In the context of this show, the use of the horizon as a reference to ideological constrictures was important. As a metaphor used since Nietzche's time, the horizon bounds one's sight and ideological outlook.

Merritt sees the horizon metaphor operating in many discourses, including tourism, an important reference for his work. In "regionalizing" the work by using material associated with the immediate environment of Halifax, he feels he is attempting to lay the groundwork for the recovery of an audience - one inundated with a mass culture which attempts to crowd distinct regional identities into cleverly wrought tourist sites. Merritt, like many of us, often feels like a tourist in his own environment. His awareness of the methods of tourism and site-making led him to work that attempts to deconstruct the strategies of tourism which infect places like the Maritimes.

Many such strategies are used by government agencies like Parks Canada. They advise "interpreters" (those who "create" historic sites) in defining sites, establishing themes, and telling stories. Merritt learned much from a book by Freeman Tilden called Interpreting Our Heritage. "Pedagogical miscellany is a bore to a man on a holiday," says Tilden. Here history functions as instrumental entertainment that uses historic and natural sites as raw material. Merritt sees his work directed at an audience which has hitherto swallowed.

the rhetoric of tourism whole. The "site" of Merritt's show, the Anna Leonowens Gallery, is located in the centre of Halifax's revitalized historic district and the show was set up through an analogy with the "interpretation centres" found at historic places everywhere.

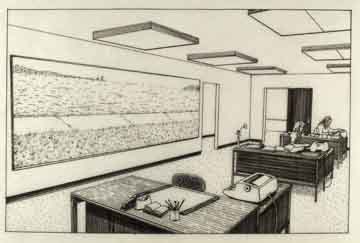

In these centres, the need to tell a story is often more important than factual truth. Although the basis for a story was also built into Merritt's show, no narrative was delivered. Instead, the viewer made her/his way among familiar visual elements in the meditative atmosphere of the art gallery. As the viewer turned from the highly abstracted versions of miners and fishermen to the small ink drawings of an office interior and a couple gazing out at the ocean, a thousand stories were possible. Most often, I think, the ink drawings were seen as subtly updated versions of the social realism of the reliefs.

The fishermen shared a wall with the drawing of a man and woman looking out at the horizon. Their backs are turned to the viewer. What are they looking at? Is the couple looking across the history of representation of themselves in images of labour? On the same wall as the miners hung the small ink drawing of the office interior. In the drawing, the workers sit beside a landscape which hangs on the office wall. Is the landscape merely a pretty picture or does it round off the analogy to underground mining?

In this show, Merritt walks the line across which deconstructive tactics can become appropriated by the ideology they seek to take apart. That the deconstructive work can be turned on its head is a threat that Merritt is wary of, and will continue to struggle against. As for this show, I think he walks the line successfully.

|

|