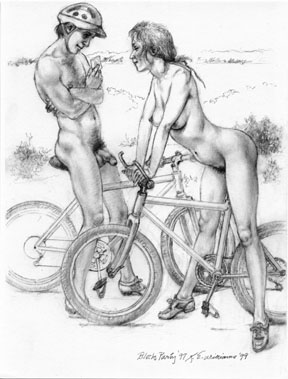

Richard Williams, Mountain Biking, 1997 from the Naked Block Party series. graphite on paper, 24.1x31.7cm. Collection of Gallery One One One; gift of the artist.

Drawing the Art of Ardour: Richard Williams's “Naked Block Party”

by Meeka Walsh

The Renaissance ideal embodied an harmonious correspondence between a being's moral and sensual needs but with the lapsarian notion that all knowledge is loss insinuating its snakey presence, such an ideal could not be attained. There was, still, the immortal soul to be dealt with. From the quandary of the irreconcilability of body and spirit, salvation and earthly pleasures, came Mannerist art. Art historian Arnold Hauser tells us that “mannerist art never confronts the spiritual as something that can be completely expressed in material form. Instead it considers it so irreducible to material form that it can only be hinted at (it is never anything but hinted at) by the distortion of form and the disruption of boundaries.” (Mannerism, the Crisis of the Renaissance and the Origins of Modern Art, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1986).

It would be a tenuous argument to place Richard Williams firmly in the Mannerist camp but there are parallels. I find them in what Hauser identifies as the distortion of form and the disruption of boundaries. The gently transgressive nature of his work is such a disruption of boundaries; he means to up-end held views, to play with social form, to tease stock moral responses and loose the thin line of mouths set in disapproval. With humour, he says, and with what he describes as a “comical fantasy,” and with the outrage provoked by challenging convention.

To extend this Mannerist play-there are visual relationships too. Helped by the abstraction of a painting's being reproduced in black and white I look at Raphael's Transfiguration, Pontormo's Descent from the Cross, Parmigianino's Madonna del collo lungo and then at pieces from Richard Williams's “The Naked Block Party” where, on the sheets there are attenuated long bodies, players clustered in ascending groupings and interacting, gesturing figures set on a raked plane. Hauser identifies the characteristics of Mannerist art: “A certain piquancy, a predilection for the subtle [well, maybe not a perfect fit for “Block Party”], the strange, the over-strained, the abstruse and yet stimulating, the pungent, the bold and the challenging. . . .” Well, why not.

Williams identified the impetus for “The Naked Block Party” as a series of letters appearing in the Winnipeg Free Press in 1997, in response to a decision by the Ontario Court of Appeal whereby women were now permitted to appear topless in the same settings in which men might also appear bare-chested, namely beaches. Williams allowed himself to imagine life in a naked community, a middle class suburb which had decided to throw a naked block party. “I decided to break out and follow the images wherever they might lead,” he wrote. “Political correctness was shrugged off along with most other systems-only ingrained self-censorship remained.” What resulted were 26 graphite drawings, an alphabet perhaps, for a new sexual language.

Decades apart in age but with some shared roots in Northern Italian, Renaissance and Mannerist painting, Richard Williams and American painter John Currin have issues in common. In a catalogue interview with curator Rochelle Steiner, Currin responded to a question about painting an image of a happy gay couple, which Steiner saw as associated with political correctness. “By creating it, it's a way of showing affection to the image. That's another reason I don't like to paint nudes all the time. It's just too easy an equation of loving the canvas, fantasizing your touch, caressing and touching a naked lady, that kind of thing. So painting Homemade Pasta [where two neatly-coiffed, happy men in aprons are preparing a meal] was just a way of having some resistance and also making an image that's intimidating in the same way that an image of a naked lady is intimidating.” (John Currin, Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; Serpentine Gallery, London and Harry Abrams, Inc, 2003).

Williams's fine graphite touch, the places where his eye and pencil linger, indicate the affection Currin speaks about and while Williams may not intend the image to be intimidating, to call the viewer up in that particular way, they are meant to be instructive and even, on occasion, didactic. Looking, you are never ambivalent as to his intended reading.

Each of the 26 drawings is introduced by a brief written statement, ostensibly culled from journalistic sources. While Williams's hand is clearly the drawing hand, the texts are cast as second hand: letters to the editor, newspaper clips, the opinions of a slightly distant overseer. The voice, sometimes in a hectoring tone, critically prods society's prim mores.

Art's history had given Williams permission to look at, and paint or draw, naked women. Scopophilia was fine. Contemporary stances have argued otherwise. It was the current culture's attention to the appropriateness of female-gazing males and to issues of representation-what Williams referred to as “ other systems”-that prompted his opening salvo of abandoning Political Correctness. Currin addressed these issues, saying he'd thought it silly to need permission to represent something but at the same time he was not unmindful of what he called “residual guilt”: “I dislike the idea that an image of a nude woman may stand for a certain idea of sin or temptation or perversity, or the opposite, of overcoming your inhibitions,” he said. “Now, I'm hesitant to make nudes because it's so common for a man to paint them. But I love the image so much that it is still a guilty pleasure.”

Like Currin, Lisa Yuskavage is an American figurative painter. Both born in 1962, they share an acute interest in representing the female body, work that is a slip to the grotesque, and a disregard for society's “ought to's.” Though given their successful reception “ought” appears to be loosening its puritanical grip.

After receiving an MFA from Yale and a period of exhibiting her work where Yuskavage felt compelled to self-censor, she said, “The well behaved work that I had been doing was killing me. I was suffocating. I deliberately changed my work in order to save myself. Being in touch with 'the vulgar' was like finally breathing air. I was free and I knew that no matter how offensive the work might be there was no turning back.” (Lisa Yuskavage, Small Paintings 1993-2004, Harry N. Abrams, 2004).

With the concurrence of Yuskavage and Currin any dilemmas impeding reading Richard Williams have been driven away. It clearly isn't only men looking at women, pencil poised. There's also Tom of Finland, Etienne and Paul P scoping out and finely drawing males as objects of absolute desire. There is G.B. Jones, a gay woman who draws women and men with unmistakable pleasure and there is Hilary Karkness and her women-only genre drawings.

Paul Cadmus, 1904-1999, was a distinguished American painter whose focus was the human figure. As a gay man his eye and brush may have favoured the male form but as a skilled professional his female subjects, while not as frequently chosen, were fully and carefully rendered. Heterosexual couplings were not his preference either, but he was a close and true observer. What I Believe, 1947-48, is an allegorical tableau in which all the figures radiating out from the central idyllic couple are naked. Cadmus himself is there, painting the future, supported by a woman who could have stepped from Botticelli's Primavera. Couples, gay and heterosexual embrace and comfort one another, or are engaged in pacific activities: reading, constructing a simple shelter, playing with animals. It is Cadmus's garden in the same way the “Block Party” is Richard Williams's wished-for neighbourhood.

One of the most engaging, and I think, fully rendered drawings in Williams's project is number 22, Mountain Biking [see above]. In this work the line is sure and unhurried. A man and a woman wearing only shoes (and in the case of the man, a helmet) looking, as exercise programmers would say, buff-and coy. In the drawing there is evidence of the cyclists' weight on their saddles-the flesh of the man's visible buttock creases a little with his sitting. The woman straddles her seat but her toes barely graze the ground. She leans forward on her handlebars, her arms extended, eyes demurely downcast-or maybe she's checking him out. And he, it appears, responds with growing interest. His arms are folded across his chest; there will be no untoward groping.

Bicycles are complex simple machines. As early, accessible modes of transportation, they were liberating. Structurally, visible really only in silhouette, they are elegant. Used by both men and women they provide a certain equivalence. A cyclist seen from behind has become an icon of desire. And, they are straddled. Williams has deftly modelled the fleshy contours of both bodies. If an award were offered for virtuoso drawing in the category of pubic hair it would be his without competition. It's a skill that speaks to the deftness of his draughtsmanship as well as to the gentleness of the man.

Paul Cadmus painted a cyclist too. Finistère, 1952, holds as its ostensible subject two young men with bicycles, resting on a stone wharf. One is mounted on his bicycle, his shorts riding up, the point of the saddle nudging the split of his buttocks. His body is turned to the other young man who leans against the sea wall, a hand on the bike's saddle. The mounted cyclist holds a long baguette in anticipation of the next meal. The other man, fingers hooked into the waist of his tight shorts gazes pensively out to sea. Figures in the background are rendered in less detail, or as caricatures. Williams does this too, focussing on the foreground activities or even, in some instances selecting only certain sections to render fully -those that carry the narrative or are necessary for structure or are of interest to him. In doing this he seems to be fetishizing his own work-a quiet withdrawal from the larger subject to the reverie of drawing. In number 15, Smoke Alarm, one of three young women sits at the drawing's right, on a picnic table. She is easy in the company of her friends and her legs are open, toes resting lightly on the bench. In this drawing each of her toes is articulated, her legs, thighs and sex drawn in full. She tilts back a little, beer in hand and the tension has caused a slight tightening in her stomach muscles. Her collarbones and the tendons in her neck are attended to. Her face is only sketched. The other two women are less fully dealt with as figures. At the sheet's lower right there is a young girl. From below her small breasts to her legs truncated at mid thigh, she is a Degas dancer. Her slightly straining rib cage, the angle made by her waist and left leg extended backward, the shaded flat belly and pre-pubescent genital area, the contraportal shift of her right leg-she could indeed be one of the young dancers Degas came often to draw, as the ballet classes practised.

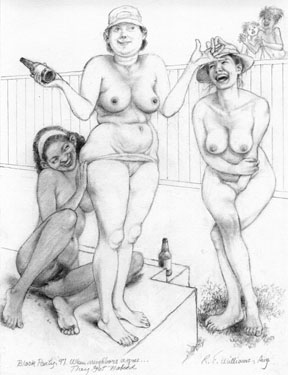

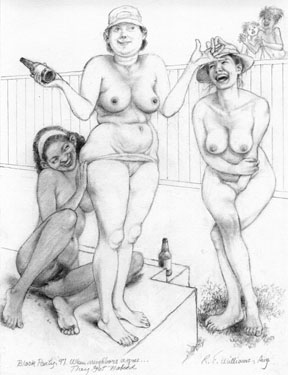

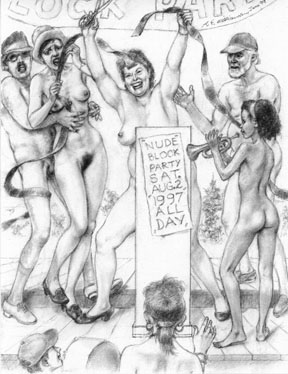

Richard Williams, When Neighbours Agree, 1997 from the Naked Block Party series. graphite on paper, 24.1x31.7cm. Collection of Gallery One One One; gift of the artist.

The drawing, number 9, When Neighbours Agree, [above] is unusual in this series. Williams's narrative tells us that three women have agreed to take off their clothes-no matter what. The central figure, a robust-bodied good sport stands like a drawing class model on a raised step. One of the other women is also on the step but she is seated. The “life model” is presented as a caricature full of jokey good humour. The other two women are also laughing but they are drawn in greater detail, each in a different manner. The woman on the right has a truly lovely face like a young Katherine Hepburn. She is ample in her proportions but with elegant winged collarbones which Williams has taken care to show. Her legs are long and shapely and the toes of one foot are cramped in futile self-control. As Williams has written in his text, “they piss themselves laughing.” With the seated figure he has drawn a young black woman who is assisting the disrobement of the central figure by tugging at her panties. Williams has rendered her with her weight shifted to one hip to show not only her fully drawn genital area but also so that we can see the droplets showing between her feet. More than in any of his pieces in this series, even those where he has shown oral sex or penetration, in this one he seems to have risked depicting something that could be read as transgressive. The toss-off humour deflects the risk but it's there still in the casual reference to the golden shower which could test the tolerance of his audience.

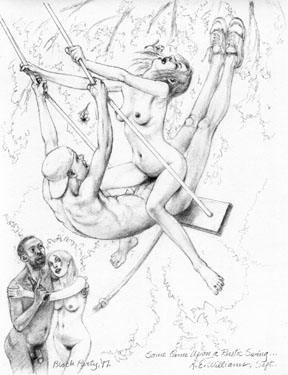

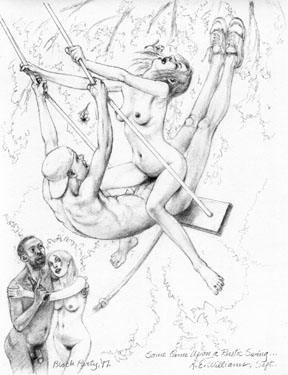

Richard Williams, Some Came Upon a Rustic Swing, 1997 from the Naked Block Party series. graphite on paper, 24.1x31.7cm. Collection of Gallery One One One; gift of the artist.

A woman straddling a man riding a swing is something of a sexual cliché. In number 13, Some Came Upon a Rustic Swing, [above] Williams proferred his own version. The spaghetti-limbed young couple give the viewer pause to ask if between them there is sufficient tension to even keep the swing in motion. Like the detailed Japanese Shunga drawings, this piece has more manner than heat. Only the young woman's slightly splayed toes show any bodily involvement. What Williams has done in many of the drawings is undercut any real indiscretion with foxy good play and a tee-hee sense of naughty primness. As he'd said in his opening statement, he was governed only by his ingrained self-censorship. However provocative the subject of “Block Party” appeared to be, he could have further loosed the reigns of discretion for a more complete engagement.

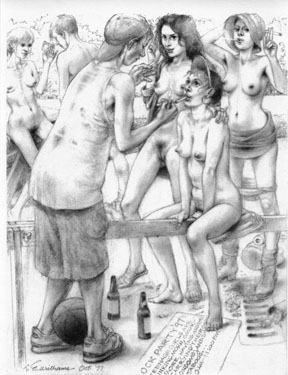

Richard Williams, Mind Games, 1997 from the Naked Block Party series. graphite on paper, 24.1x31.7cm. Collection of Gallery One One One; gift of the artist.

In contradiction to that is another of the drawings which has been executed to full sensual effect. It is number 14, Mind Games [see above]. A barricade has been set up as is usually done to demarcate block parties. One side represents nature, license, openness, freedom and all things possible. On the other is denial, constraint, lack of knowledge and all things faint and colourless. Three sirens, lorelei, avid young women approach the barricade from the Block Party. On the benighted side of the bar is the object of their predatory interest-a young basketball player. Where he stands, the heat available to him is the flame of the cigarette lighter he offers to the women, all of whom are smoking, as it were. They look at him, these three women-each with an individual, fully drawn visage-as though he were lunch. The woman in the foreground is naked but for a hat and earrings. She sits, one foot in each camp, on a towel folded on the barrier, staring up at him, a cobra to his flute. One of the women wears a loose shirt, open, and she has a face as full of knowledge as Eve's after the apple. The third woman, who blows a stream of smoke at the young man, has a towel draped around her hips or it may be her skirt bunched up. She wears hiking boots and wool socks but with her panties gathered at her knees it's not a brisk walk she's prepared for. These young women are almost vampiric in their focus. In ardour alone the skinny basketball player is trumped. The narrative balance of the piece tilts to the women. As a drawing, structurally, it does the same. Along with Williams's skill as an accomplished draughtsman, the weighty off-centredness contributes much to its interest.

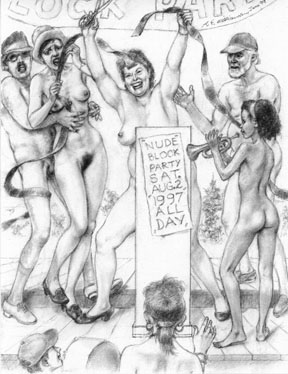

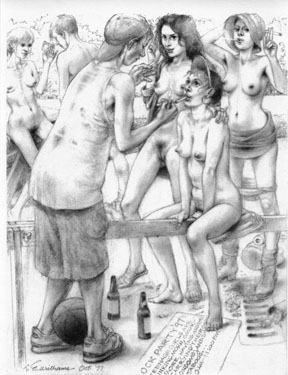

Richard Williams, The Naked Block Party 1997, 1997 from the Naked Block Party series. graphite on paper, 24.1x31.7cm. Collection of Gallery One One One; gift of the artist.

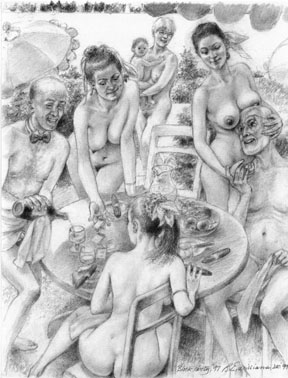

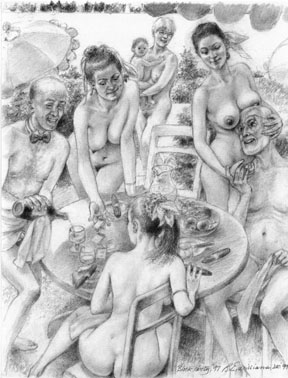

Richard Williams has drawn himself in at the Block Party's launch in number 5, The Naked Block Party 1997 [see above]. In keeping with the spirit and intent of the event he wears only a baseball cap and loafers. A young girl heralds the opening with a trumpet and stands in the drawing's foreground, just in front of the artist's genitals. He's present at the close of the series too, in number 26, The Catered Luncheon [below]. Friends are seated around a patio table. Wine and cigars for everyone. The host who pours the wine wears a bow tie and holds the bottle draped in a cloth that almost covers everything. Williams leans back in his chair, his head cushioned against the accommodating bosom of a young woman who stands behind him. A napkin covers his lap. He holds the woman's hand which he could be drawing toward the napkin. He is very much at home, comfortable and easy. In the end, however, he demurs and equivocates. But that's okay. After all, with his drawings he's already shown us much.

Richard Williams, The Catered Luncheon, 1997 from the Naked Block Party series. graphite on paper, 24.1x31.7cm. Collection of Gallery One One One; gift of the artist.

Meeka Walsh is the Editor of Border Crossings, the Winnipeg-based arts magazine.

The Richard Williams

CD-ROM includes information about other Gallery One One One projects: Gallery One One One, School of Art, Main Floor, FitzGerald Building, University of Manitoba Fort Garry campus, Winnipeg, MB, CANADA R3T 2N2. Gallery Hours: Noon to 4 PM (weekdays only).

TEL:204 474-9322 FAX:474-7605

For information please contact Robert Epp

eppr@ms.umanitoba.ca