SELF-PORTRAIT

[This piece has only ever appeared on this website.]

My Dad's parents had funny accents; they were working class folk from Leeds and Manchester who lived in Montreal's east end, where my father was born.

My mother's father was a taciturn sea caption from Nova Scotia's Eastern shore. My Mom's mom was a voluble Irish Catholic whose grandparents came to Canada as potato famine refugees. Granddad Williams didn't talk much, his wife Kathleen (née Hughes) talked a lot. Born in 1900, she survived the 1917 Halifax Explosion: "All day I tore sheets into bandages," she told me. Crossing the harbour on the Dartmouth Ferry from Halifax, she saw the whole North End in flames. My Mom said that her mom had the Black Irish in her -- that she had been blessed as a witch.

I was born in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada: six weeks later my mother and I sailed to Europe on the Cunard Liner Ibernia to join my father at an air force base in Germany. On the way we stopped off in Leeds, England to visit relatives. The opening weeks of 1955 were spent in Paris, where, to my mother's horror, someone fed me milk from a green wine bottle. My first few years were spent in Baden-Baden, a town in Germany's Black Forest once mythologized by the Nazi Martin Heidigger as a peasant enclave; today it is a gambling resort and spa. Elaborations of the photographs in my parents' leather-bound album are my only memories of that place.

We were in the Black Forest because Canadians and others were occupying a defeated Germany. My parents said no German ever mentioned the War to them. My parent's political consciousness allowed no speculation about our place in the military occupation of Germany. We were just there. My German babysitters would have been born during the German War, but in our old photo album they look like suburban Canadians.

We moved back to Greenwood, Canada, an air force base tucked in amongst the Annapolis Valley's apple farms and elm trees. Except for the fighter air craft, Greenwood was an idyllic vision out of Dylan Thomas' Fern Hill, and I had an idyllic childhood there, making little sculptures out of ant-eaten stump wood and baking mud pots in the sunny back yard. We made drawings of military battles at school that always had a nuclear resolution (depicted as mad scribbles over carefully drawn tanks and airplanes).

An air force base is a big asphalt field with houses tucked beneath trees at one side. The kids are called "air force brats" because of their smug cosmopolitan smirks. They (we) moved around the world from one military incubator to another, and each move made it easier to meet new friends and forget old ones.

When we were small, everybody was in uniform. Dad was an air force corporal and Mom was a nurse. We assumed that everybody had a uniform, and the relatives thought uniforms deserved respect, no matter what the wearer's rank.

The era of my childhood has been called a golden era by historians because no major wars happened. There were Canadian peace-keeping actions, but my recollections of air base life are serene. Preparations for nuclear war may have been the bizarre basis of our existence, but that was never discussed. The Cuban missile crisis in 1962 was the only panic I remember ever marring our well-ordered routine: we knew that the adults were very frightened. Children at Air Vice Marshall Morphee School ("A.V.M. Morphee" as it was called, making me think of morphine) were never trained, as I recall, to "duck and cover." Everyone--even the kids-- knew that staring directly at a nuclear flash is best. Asking my Dad to build an air raid shelter, as I once did, was silly (I could see his point: why prolong the suffering?)

Except when nuclear war was imminent, then, the security of a Canadian air force base was unquestioned. Parents were not afraid that their children would be kidnapped; milk bottles with change in them could be left on the doorstep overnight, and Hallowe'en candy was never tested for poison.

Discipline was strict on the base school -- I was slapped on the hand with a ruler once for "stepping out of line". After class the base brats stayed out after dark. Far into the night I would ride my fat-tired bicycle down pine needle paths and round paved, crescent-shaped streets.

We moved to Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, in 1964 when I was in the forth grade. Dartmouth is the working class sister city of the Canadian port of Halifax, linked to the bigger town by bridges and a harbour ferry. Halifax and Dartmouth are really one city made up of university people and military people, sea people and land people.

At first we lived on Crawford street near the Halifax harbour. Mental patients from the Nova Scotia Hospital wandered around our neighborhood. I can still vividly recall a woman dancing naked in a back yard as we sat on the fence chuckling. One day she disappeared back into the "mental" because, so kids told me, she threw a rock at a police car.

Garbage and potatoes were underneath our coal-covered backyard on Crawford Street. The neighborhood smelled of the gas plant down the highway. I saw a duck-tailed teenage boy split another's cheek with his fist. My brother and I dreamt of Vikings and floated a raft of railway ties in the harbour. We never did float it completely out into the North Atlantic toward pilligable villages as we longed to.

Even if I did have a perfect childhood, I nevertheless became an artist, a writer and an inventor in order to escape. I had junk drawer of supplies and reams of blue-ruled paper on which I scribbled drawings and notes and poems.

We moved to Woodlawn, a new suburb chock-a-block with half-built houses and full-grown trees to play in, and to light afire. Tom Sawyer adventures filled our days. What I remember most was a dreamy interior life, but I have always been more extroverted than I like to admit. Was I a bookish and shy child? Maybe not. I met a man a few years ago who remembered me chasing him into a lake while waving a fist full of burning bulrushes. We made tree-forts of stolen lumber from construction sites -- I suppose that was criminal activity. If a neighbour moved out, the fence was immediately dismantled for fort-building, another questionable practice. (I lovingly recall the red oxide colour of one stolen fence.) We got bored with building and started a "fort wreckers" club. We made staves to jump over streams, to fight, and to kill fish we called "suckers" as they choked up their spawning streams in Spring.

We moved to the little border town of Amherst, Nova Scotia, were I continued, then quit, then finished high school.

ART

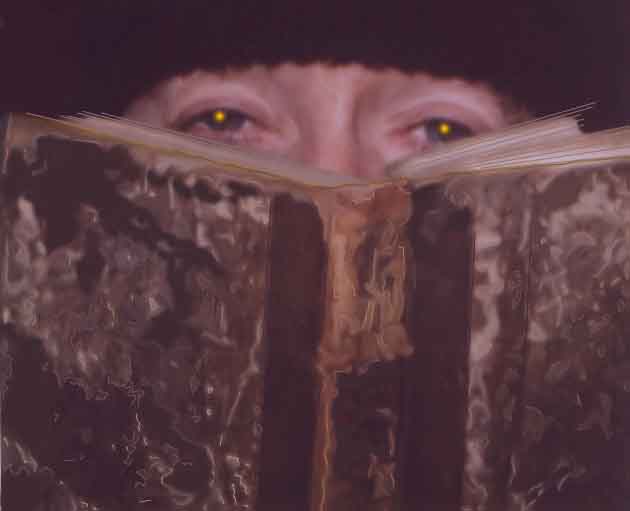

As mentioned, I made art as a young child--little stumpwood sculptures and classroom drawings. I played with the smooth soapstone Inuit carvings that my uncle brought back from Coast Guard trips, and I devoured books in the Dartmouth library. I attended Expo '67 in Montreal, and I can still see before me Paul Emile Borduas' impasto black and white abstract paintings shown there. A friend and I dashed from pavilion to pavilion at Expo collecting stamps, often by-passing the displays themselves, and I still have that small black notebook of pavilion "passport" stamps from Expo '67 that I have designated it as my first (albeit unconscious) serious work of art and my first file card sized work.

As a teenager I took painting lessons from Suzanne Paquette, a neighbor in Dartmouth and a student at the Nova Scotia College of Art & Design. She introduced me the art college, the musical Hair, and painting. In 1970--and perhaps the next summer as well (my memory fails), she took me to paint in her studio at the NSCAD. The college was on Halifax's Coburg Road at the time. It was a crowded art warehouse and not the austere conceptual temple it is often made out to have been then. Suzanne introduced me to Walter Ostrom, a ceramics professor: "This is Cliff, Walter. He's thinking of art as his bag." One of Suzanne's friends, Karl Mackeeman, was working on a painting at the time which looked to have been inspired by Chinese landscape paintings. Another of Suzanne's friends wore an army jacket and sunglasses, which he never took off "even while painting,". Suzanne showed me her thick art history texts and frightened me with tales about the rigors of art history exams.

We moved to Amherst, Nova Scotia as I entered my last year of high school.

Amherst is a small town at the geographical centre of the Maritime Provinces. It was named (as was Emily Dickenson's Amherst) after General Amherst, who was rumored to have invented germ warfare by distributing smallpox-infected blankets to Indians just as the basics of disease transmission were becoming known. Amherst (the town) once hosted Leon Trotsky as a political prisoner and Oscar Wilde as a lecturer.(Those two had a habit of showing up in the oddest of places.) Wyndam Lewis, another habitee of odd places, was born in a boat off the Amherst Shore where my family still has a house.

Amherst celebrates itself as the home of the realist painter Alex Colville, and Colville's artistic shadow still reaches across the Amherst marshes -- and my teenaged years -- like an eclipse.

I took advantage of Amherst's proximity to Mount Allison University -- Colville's alma mater -- and its splendid little gallery, the Owens Art Gallery. I took a few painting lessons from an Amherst man named Macdonald, but mostly I worked on my own. I also attended a three-day workshop at the Atlantic Christian Training Centre taught by the Trinidadian immigrant artist Michael Fernandes. I had met Michael the summer before as he was passing through Amherst. He remembers me playing guitar and walking on the railroad tracks. I ran a youth hostel during the summer months, and Fernandes became a family friend, stopping off whenever he came through town. Fernandes was the most important influence on my early life as an artist--the first real artist I had ever met--and he remains an important mentor. I have always thought of Fernandes as being what a contemporary artist should be and acting how an artist should act.

I was back in Dartmouth again during the summer of 1972, where I got my first job as a cartoonist on a government-sponsored cartoon magazine. I proposed the name "Buzzard" for the magazine, a name based on Freud's Leonardo essay. We were paid well for this work, which was sponsored by a Canadian federal summer job program called "Opportunities for Youth". I converted much of the money I made that summer into pennies, nickels and dimes, which I threw it away at local dances and down streets.

After high school I spent a year doing volunteer work in Darliston, Jamaica, teaching children at a boy's home how to draw and play guitar and piano. My art teaching consisted of buying art materials for the boys and giving them sympathetic support. I let them teach me how to make kites.

These boys were badly treated and frequently beaten. At the time beating children was acceptable in Jamaica--perhaps it still is. One time the school master Captain Johnson's strap hit the wall beside my head as we were drawing.

Backwoods Jamaica was strange, at least to me. I had arrived as an eighteen-year-old with missionary zeal, wanting to save the world, but quickly realized that the world needed saving from people like me, who might better turn their energies toward activities like art while supporting "development" through direct aid, fair trade and the support of immigration.

One of the Clifton Boys Home boys was Joe Clarence. He made schematic, "primitive" looking drawings that greatly impressed me. He hoarded precious scraps of pencil and paper for drawing, and so he appreciated the materials I gave him and the other boys. Years later, as my graduating exhibition at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design I showed Joe's drawings instead of mine.

When I was young, I was indifferent to formal art education, believing that it rotted talent. These beliefs were unconsciously Romantic, of course, and they are the ruination of many contemporary artists. I am sure these attitudes are less common now even amongst the dreamiest of today's youngsters, but at the time they made me ambivalent about the "academic" art schools which have since become my lifeblood. After high school I majored in philosophy and art history at Mount Allison while clinging ruefully to the notion that art was somehow becoming philosophy: this was a widespread idea in 1975.

I also had musical ambitions--i.e. like every other hippy I played guitar-- which I dropped in favour of my growing interest in drawing and painting.I have never given up music entirely, but now I play only as a lark with art performance groups.

While I was attending Mount Allison, I applied to get into a graphic design program in Charlottetown, P.E.I., but I was turned down. I couldn't get into an art school. At my interview Henry Purdy and Russell Stewart told me I should be at an art college. I had to agree with them, but Holland College had the only art program in Prince Edward Island, and I was committed to moving to Charlottetown for personal reasons (I had just married Kim Auld, who wanted to go to journalism school there). I became desperate to get into any art school despite my ambivalent feelings about art education-- and I needed some artistic company. Fortunately I was able to persuade Mr Purdy to admit me after I had already moved to Charlottetown.

At Holland College a few of my fellow students and I drew and painted. Occasionally we would do graphic design to get money. The school paid for life models, and it had plaster casts, so we earnestly ran ourselves through two years of self-styled nineteenth-century academic art training.

A student named Diana Cripps was very important to my work then. We have since lost touch and I have always been curious about what happened to her. Another student named Kathy Stewart was also important to my work. I exhibited in an exhibition organized by fellow students Duane Gordon and Jean-Guy Richard. Floyd Trainer began to teach at the school while I was there and I learned a great deal from him. Floyd looked like the Boston version of Van Gogh's Roulin the Postman, and he had a marvelous dry sense of humour. He taught me silkscreen printing, and I helped him make screen prints.

After Holland College and my first marriage, I moved to Alberta, Canada, where I did manual labour in Edmonton and graphic design in the oil boom town of Fort McMurray. After a year of that nonsense I returned to Halifax, where I got a summer job in the reserve army before going back to art school at NSCAD. (I needed a change and joining the army seemed radical.) Wittgenstein, Socrates, and my Dad had all joined the military, and so despite my pacifism I thought I'd have a go, too. Besides, I enjoyed the effrontery of going to the art college in uniform to register.

My studio advisor at NSCAD was Judith Mann, whom I liked very much. I especially appreciated her sense of humour. My most important teacher and influence at NSCAD was Eric Cameron. Instead of studying with Cameron, I was so fascinated by his personality, his ideas, and his work that I decided to study him. About a year before I became his student, Cameron had begun to make his "thick" paintings, a continuing project. The "thick paintings" are ordinary objects chosen in 1979-80 which Cameron is still, I believe, covering with layers of gesso. The thick paintings immediately reminded me of the obsessiveness of Joe Clarence's Jamaican drawings, and of other artists who do things because of an inner compulsion which does not necessarily depend on the feedback of an audience. I have always admired artists who work out of a kind of reasoned compulsion. I transcribed a 1982 interview I did with Cameron for Vanguard magazine, which published the piece in 1983. The Vanguard piece was the first ever published about the "thick" paintings and my first published article. As Cameron describes our encounter in his 1990 Winnipeg Art Gallery/National Gallery catalogue, he was rather surprised that I had written about him: in fact, he suggests that his own obsessive theoretical writing about himself began as a response to my art-student musings. He would have to set the record straight because this student had gotten it all wrong!

Cameron allowed his art to escape the grasp of its conceptualist program so that the art became a series of 'mistakes.' Psychological tension and repression are built into the more obsessional types of conceptual art like Cameron's. Whereas, say Jackson Pollock's mature work conveys a sense of instant volcanic release, a kind of ejaculatory burst, the images conjured by Cameron's type of conceptual art are closer to something like the geological layering of sediment.

A study of Cameron led me to take up the file card size format for my painting in 1981.

Various art-world luminaries came through the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design while I was a student there. I remember a wonderful presentation by Dan Graham about punk rock; Victor Burgin trying to get us to stop painting; Hans Haacke speaking about his political work; and Paterson Ewan showing us slides he had taken in his back yard with his hands wrapped around the paintings. I attended several talks by Robert Frank. Hilton Kramer came through the school and afterward announced that NSCAD students had "put down their video cameras and picked up their paint brushes." (I like to think that visitors saw my little corner with its 3"x5" paintings.) The presence of the art historian and critic Benjamin Buchloh, who taught contemporary art history courses at NSCAD at the time, seemed to keep everyone on edge, if not the edge. At the time contacts with the NSCAD power duo Gerald Ferguson and Garry Neill Kennedy were minimal, but Ferguson has since become an artist who interests me a great deal.

In retrospect, given his subsequent influence on the art scene in England and his untimely death, Peter Fuller's studio visit with me was a highlight of my NSCAD years. One of the painting instructors, the late John Clark, was anxious for students to meet Fuller. The future founder of the British magazine Modern Painters came into my tiny section of the painting studios, where I had gotten out some paintings based on a collage made of pieces of a Hogarth print. After a slow look, he leaned back in an Oxbridge slouch and proclaimed that I was making "concessions to conceptualism," as if I were struggling to get back through conceptualism to a more ancient art. He made me angry at the time, but I have since learned to appreciate--even share--some of his opinions.

After art school I continued my file card painting while working as a laborer, borrowing my Dad's pick-up truck to haul plaster and lathe to the dump from yuppie house renovations in North End Halifax. I also worked briefly at the Federation of Nova Scotian Heritage cataloging their book collection. (I later used notes from that project to make art.)

In 1984 I became the 11th Exhibitions Officer at Mary Sparling's Art Gallery at Mount Saint Vincent University in Halifax. Mary's rotating one-year job was much coveted locally, and I helped look after the gallery while she organized a Canada-wide campaign of coalition groups against Tory cutbacks in the arts.

Toward the end of my tenure at Mount Saint Vincent in 1985 I was offered a curatorial job at the Technical University of Nova Scotia's School of Architecture. Between 1985 and 1994 I made and exhibited art in Halifax, wrote about work and curated exhibitions.

As a painter, I continued making small paintings in what I thought was an ambitious way. As a writer I began reviewing and curating exhibitions in an unambitious way, as if a review were like a letter to a friend.

My life at the TUNS School of Architecture was mostly taken up with student requests for information. I also put together and coordinated exhibitions about architecture. It was the era of deconstruction in architectural design, and I found the milieu to be a great deal of fun--beautiful nonsense. Many students, of course, were dismayed by this era of architecture without buildings, of theory without thought, and of ideas with no place to go. I have never been interested in doing architectural design myself, but perhaps an attitude that architects have to design rubbed off on me a little. I began to look at representational painting, for example, as if everything that is represented is "designed" as much as depicted, which is a different attitude from most art school notions of, say, painting "from memory." Nothing need be incidental in a painting. For example, if I made a painting of a figure in an interior, I could "design" the chair the fictional figure sat in, etc. This may sound trivial until one actually looks at the history of painting last century in which formal manipulations in painting most often concern a variation or fugue on collections of banal things which are themselves taken--from a design point of view--for granted. Painters will formally play with the forms of a chair they depict, but they will rarely redesign that chair in their painting. In short, I drew on a means of architectural thinking to consider anew everything that went into a painting, not only in terms of the history of painting, but also in terms of the history of design.

I moved to Winnipeg in 1994, and my work entered a new phase of consolidation in which I arranged my paintings in thematic groups for exhibition while continuing to make new work: that continues as I write...

|

|