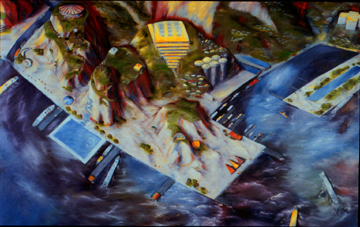

ABOVE: Eleanor Bond, Offshore Barge Draws the Beach and Sailing Communities, oil on canvas, 1989. Photograph courtesy the artist. Collection of Gallery One One One.

ELEANOR BOND'S SOCIAL CENTRES

[First published as "Architexture: The Paintings of Eleanor Bond" in the year 2000 in Winnipeg's Border Crossings magazine, issue 76, 70-71.]

Eleanor Bond's very large paintings were shown in a solo exhibition called Social Centres, which toured Canada a few years back. I saw the show at Dalhousie University. The following reflections on Bond's work are made as I think about one tiny part of the relations between art and architecture, that is, contemporary painting and the rendering of perspectives in contemporary architectural design.

Painting and architectural design have always had lots of things in common. They are two subspecies of a phylum drawing for example, but they are also separated by innumerable differences in social relations and culture. They each have their own cultures, really.

In architectural terms, Eleanor Bond's Social Centres look like imaginative "perspectives." A perspective is what architects call rendered 3-D-looking drawings with or without colour. Drawing these perspectives is a specialized activity in architectural practice. It may surprise many non-architects to know that very few architects are good at drawing perspectives. Because architectural perspectives can be worked up from plan, elevation and axonometric drawings in a mechanical way, they can be tedious things to make unless one has a flair for it. Perspectives are drawn by architects for the benefit of clients who want to see a coloured, illusionistic rendering of a building that is otherwise presented to them in floor plans and facades. Part of the problem of making a coloured perspective drawing is accuracy: what will such and such a local colour look like in a rendering of the whole building? How can scale drawings of people in the space look convincing? Perspective drawings are being made easier by computers these days, but a satisfying perspective still demands the skills of a sensitive draghtsman and a fine colourist. I should also mention that at the beginning of the design process, skill at perspective drawing can also be very useful, although there is no reason why perspective drawing should be thought of as being essential, rather than just useful, at any stage of the process of architectural design.

By contrast with the architect, the paradigmatic representational artist has a different attitude to the perspective drawing, that is, she can take it or leave it as desired. The artist is not usually designing what she sees, and so she does not need to present a whole object, but only what appears in the painting. It is a new painting she designs, and not a new building, chair, or light fixture. This difference in orientation between the artist and the architect is important to keep in mind in relation to Eleanor Bond's Social Centres, because I believe that the strength of this work depends on the artist taking by turns both the artist's point of view and the architect's point of view. I read Bond's Social Centres as both architectural proposals and paintings. Because they are both, they encourage a viewer to shift back and forth from regarding them as possible designs for buildings to regarding them as painterly fantasies of scenes which are in no way intended to be realized in actual architectural form.

Usually a representational artist approaches what she represents with an eye to what is transformed and made new in a painting, and not with an eye to transforming or suggesting design transformations in the buildings she depicts. An artist's primary concern is the painting as an object sufficient unto its aesthetic self, whereas the architect's primary concern is a three dimensional design rendered in two dimensions. The difference in orientation between our paradigmatic painter and paradigmatic architect is usually a world of difference, but in Bond's Social Centres those differences are deliberately erased.

Let me put it another way. A representational painter asks us to look through her painting in order to see what? Why, to see painted things. An architect asks us to look through her coloured perspective drawing to see what? Why, to see an architectural design, to see designed things. But when Eleanor Bond paints an imaginary Social Centre, what is she asking us to see? Why, to see both a painted architectural design and a painting which happens to have an imaginary building in it. What we see is not only a painted thing--a coloured perspective drawing of an architectural design--but also a painting in which an architectural design appears.

From the painter's point of view, in terms of the design of a painting, it does not matter whether Bond has two or ten pavilions on her "Rock Fans and Music Students Gather at the Suburban Concert Park," but an architect could not help but wonder whether or not five or six pavilions--depending on their function--might be necessary. If the painting were literally a preliminary architectural proposal, its credibility might be lessened if it were obvious that, say, twenty service buildings rather than two were needed in proportion to the lot size of the car park, but because it is a painting--and so obviously a huge and ambitious painting--we have the option of assessing it as a painting, too, or instead an architectural proposal.

It would be technically possible to build every structure that is depicted in Bond's Social Centres. Compared to the fantasies of some architects such as Soleri or Archigram, Bond's structures are plausible as real buildings. This plausibility lends the paintings a documentary air, however fanciful the buildings. In terms of conventional architectural rendering, they are, of course, loosely drawn. Bond tends to avoid rigidly drawn straight lines, something an architect would never do. The edges of most of the forms in her paintings are feathered or impressionistically rendered, but they are nevertheless drawn explicitly enough that they could be used to build actual buildings. The biggest problems for the contractors, of course, would be in gouging out the landscape forms that Bond has imagined--excavating a giant hand-shaped lake in Wisdom Lake is the Site of the Elder's Park and Communications Centre, for example, is the kind of project we associate with Hydro Quebec, the Alberta tar sands and the U.S, Army corps of Engineers. Still, technically speaking, Bond's landscaping would not be a problem.

I see Bond's Social Centres as a marvelously interesting way to reintroduce a certain twist to representational painting. The paintings suggest that there is no reason why a painter should not design everything that appears in a painting. For example, suppose one makes a painting in which a person is depicted. Make up the person's body, now design the clothing he wears. Design the chair he is sitting in while you are at it, and the calender on the wall behind his head, and the computer he is typing at. Why not? Painters needn't worry about whether the chair they depict can stand up, Bond's example is instructive. For the architect, one can gather inspiration, as so many already do in today's world of architecture-without-new-buildings, from a practice in which the rendering is the end, and not the means to an art.

|

|