COLVILLE KADLEC

[This review of Tom Smart's Alex Colville Return and Cynthia Mahoney's Inspired Halifax: The Art of Dusan Kadlec appeared in Canadian Literature, Winter 2005 #187,

170-171]

At least one internationally famous Canadian artist I know, who shall remain nameless, refuses reproduction rights to art journals unless he can vet accompanying critical texts. Sumptuously beautiful art books like Tom Smart's Alex Colville Return and Cynthia Mahoney's Inspired Halifax: The Art of Dusan Kadlec are produced under a head cold's worth of writer's chill because the artist's cooperation in required. We are right to be suspicious about these books because neither artist is dead.

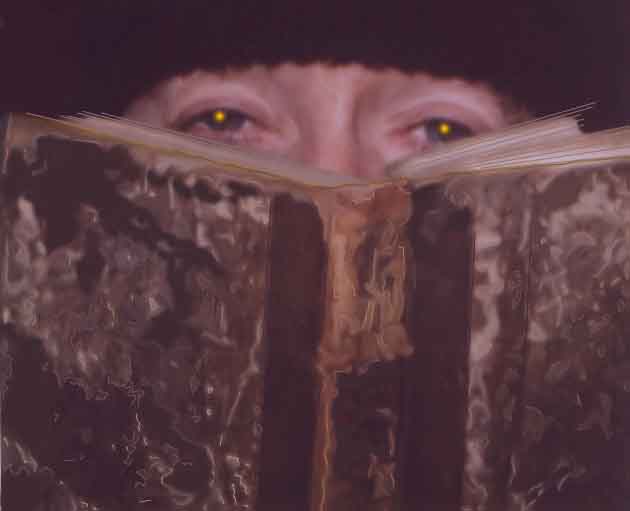

Alex Colville and Dusan Kadlec are both Nova Scotia-based conservative artists whose work is grounded in the technical principles of Renaissance painting. Both have seen themselves in conflict with an art establishment indifferent to those principles, but they share little else. Kadlec makes fantasies of a sepia-toned yesteryear, whereas Colville is the most quotidian of artists, whose much-remarked existentialism may prevent him fantasizing at all.

However much the sumptuous art book writer may be on the artist's side, a smidgen of critical credibility is a requirement -- at least for us. Cynthia Mahoney promotes Dusan Kadlec, and simple promotion will not do. Tom Smart instead grapples with the legend and art of Alex Colville from a laudable distance: his prose is beautiful, as cool and precise as Colville's paintings; Maloney's is not. Like Smart's previous book about Mary Pratt, another Atlantic Realist, Alex Colville Return does not flinch from explaining the author's differences with the artist, or from presenting his own conceptual scheme about the artist's work. Smart is not writing hagiography, and it is made tactfully clear when he disagrees with Colville.

Smart argues that Colville's experience as a Canadian soldier/artist, one of the first to enter the Nazis' Belsen Burgen concentration camp, made his subsequent art a reaction to personal trauma. Like Wayne Koestenbaum, who a few years ago provided a trauma diagnosis to explain Andy Warhol's remoteness, Smart attributes Colville's cool touch and emotional distance to bad experiences and personal psychology. (Mark Cheetham's unsumptuous Alex Colville: The Observer Observed remains my favorite Colville book because it exposes the nasty side of Colville's conservatism, for example the artist's casual dismissal of other contemporary artists and his disgraceful denunciations of state-supported art agencies like the Canada Council for the Arts, which, despite the artist's protests, has indirectly helped his career by supporting Canadian public galleries in which he shows his work.)

By contrast, Mahoney can't muster a defense of Kadlec's historical paintings in terms of the realism-battles-abstract-art gambit that Colville and many other artists abandoned years ago, or, indeed in terms of anything else. (In fact, Colville picked up a habit, likely from the American realist Andrew Wyeth, of describing certain stages of a work in progress as "abstract.") Mahoney also makes some regrettable errors of fact and emphasis in her book, suggesting for example that Expo 67 happened in 1968, and characterizing Halifax's early 1970s art scene not in terms of the (at the time) burgeoning conceptual art centre called the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, but instead by reference the backwardness of the era's very few Halagonian commercial art galleries. Such mistakes are unworthy of a book about an artist who himself makes a kind of historical fiction based on meticulous study.

Mahoney misses an opportunity to make an argument that some might for Kadlec that would position his work in terms of the cinema, as if he were making Rubens-like sketches for the sets of a major motion picture about history. If Kadlec's art suggests a past that never was, it also reminds us that we live retro-dominated lives. Conservative artists, after all, want the future to look like an idealized past.

The Colville and Kadlec books offer different perspectives on what it means to be a conservative artist today. Smart succeeds, Maloney fails.

|

|