DADA DATA

(Two exhibitions shown simultaneously at the Dalhousie Art Gallery: Fluxus :A Conceptual Country, curated by Estera Milman, and a video survey called Corpus Loquendi, Body for Speaking curated by Jan Peacock.)

[First published as DADA DATA:REVIVAL OR WHAT in Arts Atlantic 50, 1994, 28-29.]

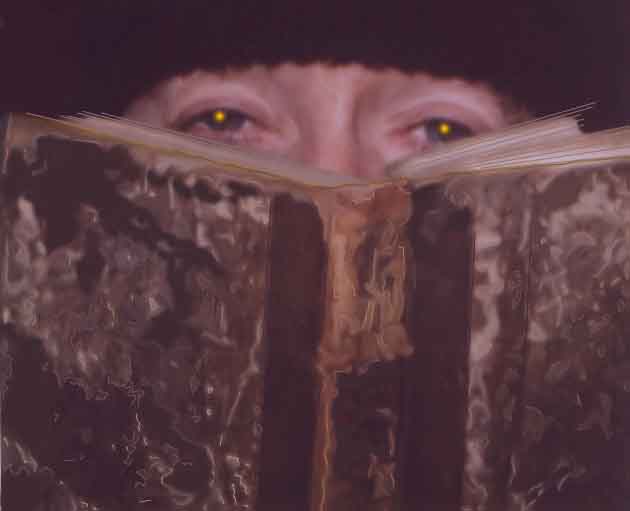

These exhibitions had Dada in common. "Dada" has taken many forms since it began as an anti-art movement in the wake of Futurism and Cubism. Its heyday was 1915-20, but the Dada spirit is as cyclical as flare pants. Dada revivals are immediately entombed in books and retrospectives, codified, assimilated, overtaken by history, put to bed as documentation, documentation of documentation, and documentation of what can't really be documented, and so new artists can easily learn the lyrics of cacophonous songs first sung almost a century ago by draft-dodging Dadaists in Zurich. Dada has also become, thanks to artists such as Marcel Duchamp, the theoretical physics of art, a game in which no experiment is too trivial for pursuit or for careful documentation, an artistic Taoism in which the Way can be Any Way: art without art; video without television; painting without easels; sculpture without materials; performance without an audience; craft without skill.

Created by artistic outsiders, the techniques of Fluxus and Dada are now the stock in trade of advertisers and music video producers, and so some contemporary Dada-inspired video artists see their work simply as the beginnings of a television or movie career. One always hopes for a true Dada revival, but what if the Dada spirit in art really is dead, and not just dead again? What if Dada has finally become indistinguishable from the popular culture which it had a part in creating? Seeing a John Lennon work in Fluxus: A Conceptual Country makes one suspect that Fluxus served the big world of popular culture the way abstract painting once served commercial design, as "research." Did Lennon appropriate Dada and Fluxus the way Yves Saint Laurent appropriated Mondrian paintings for dress designs? A different family of resemblances comes into play, but that hardly matters.

Like their Dada forbears and many of the video artists who would follow them, the Fluxus artists of the 1950s and 1960s celebrated ephemeral, everyday and obscure things in a self-conscious manner. They may well have begun, just as the original Dada artists did before them, with small critical interventions and modest events, but eventually the big monuments got built --the Christos and the Beuys sculptures--and the big archives were made, such as the Alternative Traditions in the Contemporary Arts of the University of Iowa.

After an outburst, Dada retreats back into the academy to hibernate in wound-licking documentation, mostly with full cooperation of the artists. As one of the original Dadaists Hans Richter put it:

None of us thought that Dada was "for eternity". On the contrary we lived in and for the moment. The fact that so many pieces of evidence still exist proves that among the carefree grasshoppers there were a few careful ants. --Hans Richter, Dada Art and Anti-art, New York and Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1978 (1965), p.10

The "ants" rule of Dada art was recently spelt out by Simon Ford in his review of the Tate Gallery's Summer 1994 Fluxus show: "The movement that is best documented and promoted in its day stands the best chance of being reevaluated in the future." ["Fluxshoe Shuffle," Simon Ford, Art Monthly, pp. 15-17] The scramble to control how documentation is interpreted is half of any Dada revival. As Peacock puts it in relation to Dada-influenced video art:

Even the stated intentions of the artists get continually revised by the artists themselves over the years. They, too, are subject to all kinds of influences--art propaganda, trendiness, Zeitgeist--whose argots or "shop talk" they may use to account for their oeuvre-du-jour, but whose effect on the work may be temporal rather than integral to it outside of the moment.--Jan Peacock, Corpus Loquendi Body for Speaking, Halifax: Dalhousie Art Gallery, p.8

More traditional art such as easel painting and sculpture survives as its own durable documentation, but Dada disappears quickly into life, and so artist/academics must scramble to reconstruct it for history, and for its revival.

The benchmark of these reconstructions is Robert Motherwell's 1951 book The Dada Painters and Poets , which lead to a rebirth of Dada sensibility in the 1950s and 1960s amongst Fluxus artists and the video artists of the post-1967 Nova Scotia College of Art & Design:

When this book was originally published, it was the first anthology in English of Dada writings, and the most comprehensive Dada anthology in any language. Now, thirty years later, it remains the most comprehensive and important anthology of Dada writings in any language, and a fascinating and very readable book...[I]t stimulated critical and scholarly interest in Dada, and it contributed to a revival of the Dada spirit among working artists and writers."--Jack D. Flam, [foreword to]The Dada Painters and Poets, edited by Robert Motherwell, Boston: Wittenborn Art Books Inc., 1981, p.xi.

Most Dada-inspired art--for example the Fluxus work and video tapes in these exhibitions-- is experienced only as documentation in heavily-mediated vehicles like retrospective exhibitions, books and documentary films. Some Dada-inspired work is or was almost invisible, and it can be strange in strange ways, and so it must be seat belted securely into a book or an exhibition for a smooth ride: otherwise what is ephemeral stays ephemeral, anti-art stays anti-art, obscure acts remain obscure--which is not a bad thing, except that we need to be reminded of real cultural alternatives, and not just managed mass-alternatives to mainstream cultures.

Jan Peacock's exhibition of 5 1/2 hours of video art made between the years 1972 and 1982 sets the stage for such a revival. The show's catalogue was inventively designed, a folder with insert sheets and a brochure. The catalogue essay is mostly lucid and straightforward--writing by an artist with a point of view. But she calls her project "revisionist," a meaningless buzzword, and she uses Foucault's irritating "body" jargon (as in "body-centred") when terms like "artists' video" would suffice. I find other Peacock terminology-- "dumb," "raw," "rude and lewd," "self-indulgent and narcissistic," and "boring"-- usefully concrete.

(Dalhousie organized a panel discussion about the show which included Peacock, critic Peggy Gale and contributing artists Eric Cameron and David Askevold. The evening earned itself a small place in the history of art in Halifax because of Cameron's focus on his relationship with the Nova Scotia College of Art & Design, where he once ran the Graduate Program, and because of his take on the general topic of sexuality in his work. )

Peacock gathered together representative works of a new art form:

The "birth" of video art has become a kind of folk tale familiar to all video artists: in New York in 1965, the Fluxus artist Nam Jun Paik bought the first Sony Portapak--the first on North American soil, and the first portable video equipment ever to fall into the hands of an artist. The story goes that Paik recorded his way downtown in a taxicab, shooting out the window, then played back the tape when he arrived at the Cafe A Go Go in Greenwich Village. This was the first "video art."

--Jan Peacock, Corpus Loquendi Body for Speaking, Halifax: Dalhousie Art Gallery, p.10

By the 1980s video art had evolved:

Gone from the scene were artists who occasionally picked up a video camera, but whose more recognized work was carried out in other media. What had emerged in Halifax, across Canada and internationally, was an area of artistic production with its own specialized interests, language, institutions and practitioners. --Jan Peacock, Corpus Loquendi Body for Speaking, Halifax: Dalhousie Art Gallery, p.6

In her catalogue essay, which makes a very good introduction to video art, Peacock succinctly connects the Fluxus exhibition, which shared space at Dalhousie Art Gallery, to the video art included in her exhibition:

A renewed interest in Dada (via the Fluxus movement) and a rising consciousness of "commodity fetishism" in the art establishment (via the Art & Language group) supplied conceptually-based artists with reasons to be friendly towards video.--Jan Peacock, Corpus Loquendi Body for Speaking, Halifax: Dalhousie Art Gallery, p.11

Estera Milman's Fluxus show was a beautiful and obsessively packaged landfill of boxes with objects, printed matter, collage, sculptural machines, clothing and musical notation. As Peacock does for video art, Milman carefully establishes a Dada pedigree for Fluxus:

Historiographically speaking, it was the resurgence of interest in Dada that was also responsible for the conviction that art activity must be withdrawn from its special status as rarefied art experience and resituated within the larger realm of the everyday experience of every man, a belief that informed the art activities of the Japanese Gutai Group, the French Le Nouveau Realisme circle, John Cage and his students at both the Black Mountain College and the New School for Social Research, and the groups of artists who performed at Yoko Ono's loft on Chambers Street and George Maciunas and Almus Salcius' AG Gallery, many of whom were later to become participants in Fluxus.--Estera Milman, Fluxus: A Conceptual Country, Providence: Rhode Island School of Design, 1992, p. 12

and...

The essay briefly outlines some of the uncanny coincidences between the birth of Dada and the birth of Fluxus, charts the adoption of similar ahistorical strategies by members of both movements as they attempted to position themselves historically and questions our assumption that democratization of the arts is the natural result of artistic actions that proportedly attempt to break down the line of demarcation between art and life. --Estera Milman, "Historical Precedents, Trans-historical Strategies, and the Myth of Democratization" --Estera Milman, Fluxus: A Conceptual Country, Providence: Rhode Island School of Design, 1992, p.17

The necessities of academic packaging in these exhibitions got some negative reactions: why should loaves of bread from a 1960s "happening" be treated like crumbs from the Last Supper? If a video tape such as Ed Slopek's was once part of an installation at the Confederation Centre in 1978, why is it viewed today on state-of-the-art television equipment in the presence of an ancient videotape machine in a plexi case?

I found the ephemera of these exhibitions to be captivating. Small things gave the work nostalgic allure, for example: Dorit Cypis' striped sweater; Vito Acconci's weight gain while tape-making; Susan Britton's cigarette; Wendy Geller's bedsit; the form of Robert Watts' Feather Dress; the presence of a John Lennon work; the conventions of graphic design of a George Maciunas poster; the box of ordinary 25-year-old objects within an exhibition display box; the flicker off Ed Slopek's face. At its worst, some of the work looked like meaningless agglomerations of old stuff, and meditations about it became anthropological as one contemplated the everyday differences between ordinary objects old and new.

When Dada cannot be imagined by means of its documents or by the physical stuff it leaves behind--Hugo Ball forbid-- it becomes mere data, interesting only for the technical beauties of its presentation.

|

|