YVON GALLANT

[First published at "Yvon Gallant" (book review) in Arts Atlantic 54, Winter 1996, 70.]

I was in Vancouver recently visiting with Charlotte Townsend Gault. While we puzzled out the beauties of one of her Yvon Gallant paintings, she told me about an extraordinary supper Gallant once honoured her with in Moncton by creating an enchanted environment in his small apartment. The artist decorated his place entirely in white cloth for the ritualized consumption of a home-cooked Acadian stew. Rounding off the occasion, he presented Charlotte with gifts of junk jewellery.

I was delighted when, upon my return to Winnipeg, a new book about Yvon Gallant had arrived for me to review. Yvon Gallant Based on a True Story was a chance for me to think again about Gallant and Acadian culture.

There is some agreement in Atlantic Canada among artists and curators about Gallant's importance. These claims are made concrete in this book's beautiful colour reproductions, bilingual texts, expensive binding, and thoughtful, poetic writing. It includes articles, poems and pensees by Terry Graff, Helene Harbec, Serge Morin, Gerald Leblanc, Romeo Savoie, Charles Guilbert, Nancy Morin, Elaine Amyot, and Nancy King-Schofield. Yvon Gallant Based on a True Story is like a tribute album in which the artist's paintings are sung. If Hermenegilde Chaisson is the undisputed intellectual and moral leader of the world of Acadian visual art, this book makes a case that Gallant is surely Acadia's foremost living painter, and perhaps the most significant visual artist to grace Acadia's long, embattled and tragic history.

But can we believe any glossy tribute to a contemporary artist? The art world has become so narrowly political that one may question the validity of a consensus which produces such a tribute. Why will Canada grant an artist the nod of such a beautiful book if it chooses not to grant the same artist a decent living from his art? Is it fair to bring such a debate into the discussion of art publishing? This book retails for $39.95--a fair price--but I bet a savvy art collector could get an original Gallant drawing from the artist for only a little more. Whether or not that assertion is literally true, it is fair to ask why it easier for Yvon Gallant to be honoured with a book as a great Acadian painter than it is for he and his Acadian colleagues to make a living from their art.

Acadia is a myth which exists most vividly in the work and language of its artists. However much I respect the writers involved in this project, I bristle at the parts of this book which seem to support an irrational, romantic, or nationalistic conception of Gallant's art. The rhetoric of nationalism is always an appeal to intuitive feelings and against reason. Nationalism is an unreasonable idea, so it can't easily be defended by rational argument. The wonder of Acadia is that it is not a nation. Because much good art is intuitively made, it is easy prey for appropriation in support of nationalist and irrationalist arguments, which falsely mirror the sidelong logic of artistic creation. It is dangerous for artists, whether Acadian or not, to allow their work to be seen to support nationalisms of any sort, however petty. Even cultural nationalism, which we liberals are all too eager to support in the case of losing causes, is a curse. I must object to critical efforts which make an Acadian cultural nationalist allegory out of Gallant's art, just as I must reject regionalisms of all sorts which seem make of local art an ethnic cult.

There are ways to regard Gallant's art which needn't arouse in the critical viewer a false dichotomy between local versus internationalist art which animates many of this book's arguments. Gallant makes sophisticated paintings which should not be seen as a mere post-modern play on the margins, but as an important expression of a world-wide cultural condition in which there are only margins.

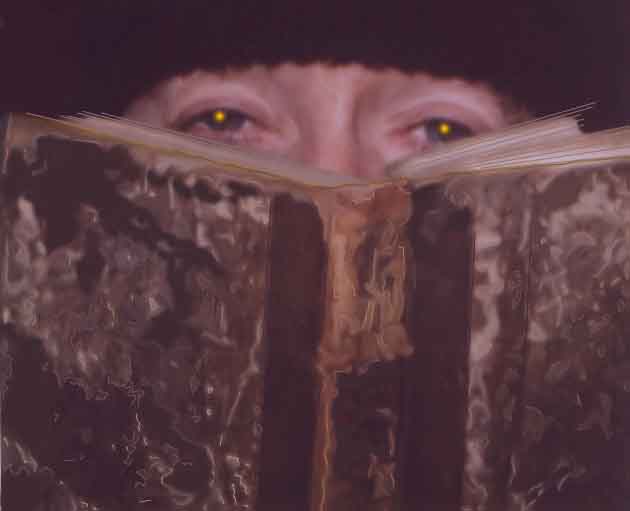

Gallant's paintings are as reminiscent of Matisse as they are of Maritime folk art--this is pointed out by several of this anthology's writers. He is technically audacious, for example when he leaves some areas of paint delineated by black lines while others float free, almost daring a viewer to outline them as well. The black lines around forms also dare a viewer to call them crude and elegant. Gallant obviously wants a painting to work structurally, and that ambition is hardly typical of postmodern painters. Such content as a cat with a thermometer up its ass, a flasher, and banal everyday occurrences may be also be better positioned better within a traditionally modernist register of the depiction of everyday life than within a postmodern paradigm which would have the local artist fill the work with tribal markers. My point is that the positioning of Gallant's work as regional or marginal by many of the writers of this book has less to do with any necessity the work may insist upon than these writers would think.

Perhaps the big exhibition at the Confederation Centre and a sumptuous book created from it is a turning point in Gallant's career, the last time that his art is addressed as marginal, regionalist activity before it is given attention simply as significant art made in and for contemporary life.

|

|