|

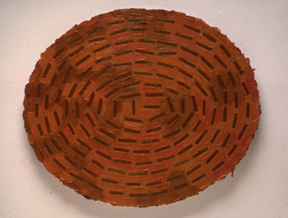

NEWTON'S PRISM: LAYER PAINTING: 6-28 February 2003 Public opening and reception: Thursday 6 February at 3 PM. Talk by Doug Lewis Wednesday 12 February at NOON. Talk by Eric Cameron Thursday 13 February at NOON. Talk by Cliff Eyland Wednesday 26 February at 7 PM. Curated by Cliff Eyland. JOHN ARMSTRONG John Armstrong web site John Armstrong's generation has lots of reasons not to paint at all. The artist on his mid-1970s art school days: I was born in Toronto in 1955, and grew up in a Toronto suburb. At that time [this] setting offered a relatively homogeneous, Anglo-Saxon North American horizon inflected by cultural ties to Britain. Art was painting, and ‘Canadian art’ was, for Torontonians, a group of largely Toronto-based painters who had worked in the late 1920s and early 30s to develop a nationalistic school of symbolic landscape art, painted in a Post-Impressionist manner. These artists would venture out into the ‘North’ and register their motifs en plein air on intimately scaled panels which they would later work up in larger, more stylized studio versions. The European old masters lurked in the back of our consciousness as distant generative fathers. Canadian art was understood to be different. [This quotation and those that follow are from an unpublished 1996 statement that Armstrong used as the basis for an artist's talk at the Institut für Kunst in Erfurt, Germany.] Armstrong switched from York University to Mount Allison in 1976 during the third year of his undergraduate degree, as if he were working out the conservatism of Canadian painting as it was presented to him in his Canadian youth. Even though the realist painter Alex Colville had left Mount Allison University's fine art faculty in 1963, the school's reputation as the epicenter of an informal art movement called Atlantic Realism continued unabated perhaps because of the continuing presence of faculty realists such as Ted Pulford and David Silverberg. However, the Sackville, New Brunswick school briefly embraced the avant-garde in the mid-1970s just before Armstrong arrived. Mount Allison faculty such as video artist Colin Campbell and curator Chris Youngs had just begun to enliven the Sackville scene, both having had just left Mount A. as Armstrong took up residence. (It is worth noting that Young's exhibition programming was in place at the Owens Art Gallery as Armstrong arrived) . Harold Feist was one of Armstrong's Mount Allison tutors: he gave Armstrong respectful and open support. (Feist was a well-known maker of post-painterly abstract paintings). Armstrong also fondly recalls the art historian Merv Crooker, who was a gifted lecturer, and Virgil Hammock, an idiosyncratic draughtsperson, art writer and sometime head of the department. Back then "the students were hipper than the faculty and did whatever they wanted." Armstrong's classmates included artists Diane Bos, Carmelo Arnoldin and Lucy Hogg as well as playwright Graham Smith and theatre director Matthew Jocelyn. Armstrong took advantage of the proximity of Halifax's Nova Scotia College of Art and Design during his Mount Allison years. He visited Gary Neill Kennedy in his studio at the time Kennedy was working on his layer paintings, and made a body of work that was explicitly influenced by Kennedy. Kennedy's work of that period, more than the Mount Allison faculty's work, contributed to the development of Armstrong's future painting as well, especially in Armstrong's longstanding interest in adjusting and layering the paintings' grounds to accommodate the figural elements in his paintings. As with Kennedy's paintings of the 1970s, the history of the manufacture of Armstrong's paintings may be seen by looking at the edges of many Armstrong works, which are crusty and dense. The art schools I attended in Canada (in Toronto and in Sackville, New Brunswick) in the mid-1970s presented conflicted views of painting in relation to contemporary art practice, and generally tended to think of vital contemporary art as being American in origin. One camp held up heroic-scale American abstractionist painting as the model; the other camp was highly suspicious of painting as a viable vehicle for contemporary practice, and characterized painting as being mired in Eurocentric, patriarchal transcendentalism and, further, as participating in consumer commodity exchange. The [proposed] antidotes to painting were the more art historically innocent media of performance, video, and installation. Artworks in these media often referred to the ‘real’ experiences, or even to the actual body of the artist. These experiences could be as formal or procedural as abstract painting’s own conventions, or they could address social experience such as gender, sexual orientation, and, in rare cases, class or race. (The notion that one did either abstract painting or dealt with ‘content’ in another medium was a silly dichotomy.) The necessity of producing an object was also in question as was the usefulness of exhibiting in the anodyne space of modernist white cube galleries. Again, the models for performative or conceptual art were most often American. (ibid.)  After making his Kennedy-inspired "layer" paintings (mixed media on galvanized steel, see above) in the early eighties Armstrong began to use text (in English and French - the artist is bilingual) in his paintings - names ("Gilles"); nineteenth- and twentieth-century brand names ("Jim Dandy" "Tru-touch", "Lou" ), headlines, phrases, one-line fragments, complete sentences ("I AM NOT AN EIGHT-DAY CLOCK") and even tombstone inscriptions mixed up with advertising images painted in a loose style reminiscent of pulp fiction cover paintings. Other works were abstract with text that looked as though it were inscribed in a frosted cake. And all the while, John Armstrong painted roses (perhaps a sly reference to 'layered' paintings?): In 1990, my visual vocabulary sorted itself out to include superimposed male first names derived from commercial products, floating on elaborated grounds reminiscent of 1950s abstractionist painting surfaces, and framed by two-dimensional arrangements of roses. The floral borders and some of the text was loosely based on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century pioneer headstones which I had made sketches of that summer while living in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Although the funereal references in the finished paintings are not overwhelming, I came to think of them as marking out not so much the death of painting as the death of the male hegemony in painting — given the preponderance of male names. (I don’t mean to suggest that this suggestion of the funereal is anyway melancholic, or even to do with the killing of a name; in point of fact, given the many hours that comprise the manufacture of my paintings, I evolved an affectionate relationship to the possibility of the demise of the names.) The paintings’ overall appearance is anachronistic, with elements that might be associated with Victorian through modern design. Being composed of many layers of paint as well as incredibly fussy, intricate passages, I had hoped that they might further point to the difficulty of rendering or reading time: by not easily disclosing just how long it might have taken to paint such a picture. Of course, the whole procedure of making an easel painting of actual cut roses is in itself technologically and anesthetically outmoded. Roses may lend themselves quite readily to such an enterprise as their own meaning is so trafficked as to be nearly impossible to pin down. But despite all of this bracketed and conditional hedging about (and I do hope that my paintings do not read as assemblages of parodic winks), roses and other foliate bits can be handily edged along into the treacherous territory of the beautiful. Gallery One One One acknowledges generous support by The Canada Council for the Arts, The Manitoba Arts Council, SOFA faculty, staff and volunteers. The CD-ROM publication Newton's Prism: Layer Painting includes material about other Gallery One One One shows: $20.00 plus shipping = $25.00 payable to Gallery One One One, School of Art, Main Floor, FitzGerald Building, University of Manitoba Fort Garry campus, Winnipeg, MB, CANADA R3T 2N2 TEL:204 474-9322 FAX:474-7605 For information please contact Robert Epp

eppr@ms.umanitoba.ca |