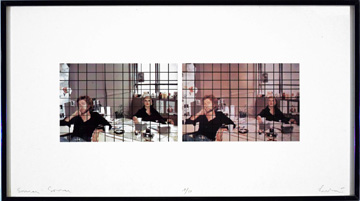

Gordon Lebredt, Source/Source, 1977, offset lithograph, 55.9 x 27.9 cm. Photo: Ernest Mayer.

GORDON LEBREDT: BY THE NUMBERS

Curated by Robert Epp

Gallery One One One

November 10, 2005 - January 27, 2006

SOME PERSONAL NOTES ABOUT GORDON LEBREDT'S

"TRUTH IN PAINTING"

by Cliff Eyland.

The reference in my title is not only to Jacques Derrida’s book The Truth in Painting [trans. Geoff Bennington and Ian McLeod, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987] but more importantly to Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s translation of Jacques Derrida’s Of Grammatology, [Baltimore and London, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976] the first to appear in English. (Gordon Lebredt, who was a young artist then, found Spivak’s book not at the University of Manitoba, but at the Winnipeg Public Library downtown. One must never assume anything about the tastes of inner city readers!)

I was also an art student in the late 1970s and early 1980s, (I am a little younger than Lebredt) and I too fell briefly under Derrida’s spell (in Halifax not Winnipeg). Back then I did an art project in Derrida’s honour by compiling some of the spelling mistakes in Spivak’s translation:

page iv, trans. preface: line 3 from the top: "socio-ecoimics" should read "socio-economics"

page 33, line 29 "anwser" should read "answer"

page 38, line 16: "typranny" should read "tyranny"

page 136, line 16 from the bottom: "itsef" should read "itself"

page 139, line 23: "the already-three-ness" should read "already-there-ness"

page 163, line 9 from the top: "...what writing it..." should read "...what writing is..."

page 163, line 7 and 6 from the bottom: "It it certainly..." should read "it is certainly"

page 168, line 3 from the top: “exterioirty" should read “exteriority”

page 215, first line: the word "suboridnated" should read "subordinated"

page 240, sixteenth line from the top: the word "produecs" should read "produces"

page 265, ninth line from the bottom "without ill-eflect" should read "without ill-effect"

page 284, line 3 from the top: "violent contorsions" should read "violent contortions"

Why would a painter do that? Or, as Lebredt did at roughly the same time “[propose] that images are composed of ‘discrete grammars,’ a collection of marks that transmit meaning to us, not unlike the diacritical marks that constitute writing.”? [see Robert Epp’s essay on this web site]. Derrida’s allegiance to the “grapheme” over the phoneme was attractive to artists. He cared about marks as much as any painter. Twenty-five years ago I thought that Spivak wanted us to pay special attention to the graphic nature of Derrida’s printed words by misspelling them (!) What better way to call attention to the bewitchment that has us conjure fanciful things from the arbitrary signs of writing? For Lebredt, who was very systematic about his art making, the strange aspect of painting that mostly requires one to make arbitrary marks that only later in the painting process carry signification became, at least as I see it, his obsession.

Derrida’s injunction against the bewitchment of presence in language has always both rattled and attracted visual artists, because artists believe that the physical objects they make are real, and that the marks they make are especially real, (I am tempted to put the word “real” in scare quotes here). Attention to process entails pulling back the curtain of illusion because, for example, a painter’s application of paint on any particular few square centimetres is usually a completely “abstract” process. The stubborn resistance of materials to one’s will is, of course, everyone’s lot, and artists do not have a monopoly on the problems of illusion and truth, so let’s put it this way: paint has to be tricked into submission, and many artists do not like to play tricks.

Lebredt’s concern for the proper framing of his early work was very much an issue for artists in the 1970s and early 1980s, when the popularity of institutional critiques, that is the idea that the art institution defines and frames art, was common. The artist Daniel Buren was a leading theorist of “framing” then, and, to get a little personal, I once wrote an essay for Benjamin H.D. Buchloh in which I naively and indignantly protested that Buren’s strategy depended on the museum for its success -- which of course was Buren’s entire point. I brought this up with the artist himself, who was a NSCAD visitor: how (retrospectively) embarrassing!

(To refresh your memory, Daniel Buren has and does make stripes that are always the same width and then puts them everywhere. As I write they under-gird the steps of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago in a temporary installation. His work has recently been the subject of a retrospective at the Guggenheim in New York. Lebredt is a much subtler, and that means to me a much better, artist than Buren: Buren is incapable of poetry.)

The recently revived interest in the super-realist painter of people and cars Robert Bechtle will remind viewers of this Lebredt exhibition that the era of Lebredt’s youth was dominated by hyper realist art, at least within the commercial gallery system. The Burens of the art world were then and may still be at the theoretical centre of the art discourse, but there is always some commercial movement in art that supersedes the theorists in popularity. The consequence of Lebredt’s interest in both Derrida and super-realism results in, for example, Epokhé (1974-75), a Bechtle-like super-realist car and figure painting with an enigmatic text that floats on top (reconstructed in this exhibition as the artist originally intended) in a way that gives one the feeling that Lebredt may have been interested in collaging whole art movements and not just styles. When Lebredt floats (not paints but floats) a text over a “finished” realist painting he both restores the work even as he obscures it. The transparency of the super-realist painting must always have bothered him, and so he interrupts a viewer’s attention by making the painting a palimpsest.

The restoration of Lebredt’s early art is the basis of this show, but Lebredt also means (I think) to continue or even to revive a debate about truth and representation in art that seemed to have been left hanging by history as Derrida passed out of fashion in the early 1990s. Why do we no longer analyse images as if they matter?

The Gordon Lebredt: By the Numbers CD-ROM includes links to other Gallery One One One projects: Gallery One One One, School of Art, Main Floor, FitzGerald Building, University of Manitoba Fort Garry campus, Winnipeg, MB, CANADA R3T 2N2. Gallery Hours: Noon to 4 PM (weekdays only).

TEL:204 474-9322 FAX:474-7605

For information please contact Robert Epp

eppr@ms.umanitoba.ca