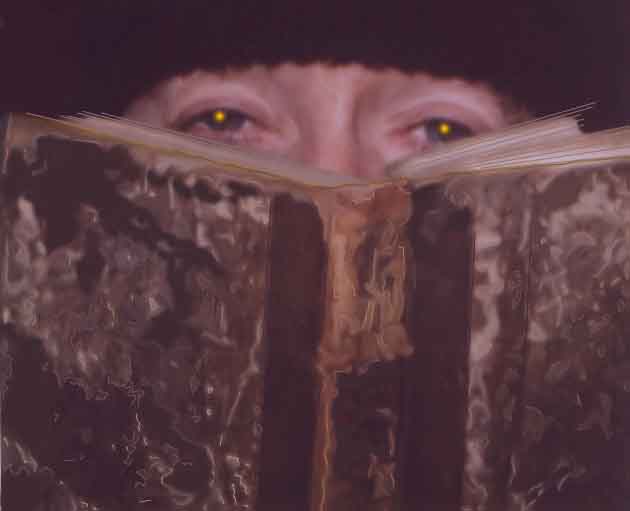

SOME CRITICAL COUNTENANCES,

Alan Harding MacKay with Charlotte Townsend-Gault

Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, (February 1989)

The politics of personality and art-world authority figure heavily in MacKay's long brown paper painting of Canadian art-world characters. Several points to ponder: This painting was made by a curator and painter who is himself a figure of authority in the Canadian art world - someone to be reckoned with.

The curator of the exhibition eschewed the traditional role of a curator as a slightly distanced chooser of work. Townsend-Gault collaborated in making the work, the exhibition, and the catalogue.

The portrayal of art world authorities (see below) in the painting begs interesting questions about Canada's art patronage system.

Curatorial projects are always collaborations among artists and curators. Charlotte Townsend-Gault and Alan Harding MacKay make this situation plain. MacKay painted a ribbon of Canadian Art world personalities "a tracing of my own contacts" he says, "a slice of the fabric" of the Canadian art world. As an enlightened patron and a knowledgeable friend, Townsend-Gault collaborated with comments, suggestions and encouragement while writing the exhibition's catalogue text.

MacKay traces his own path through the art world as an artist and arts administrator (which has recently lead him to a double career as director of Toronto's Power Plant and painter.) Townsend-Gault and MacKay knew from the beginning that their project was a portrait project; they developed it out of correspondence and meetings throughout MacKay's years in Switzerland and Canada.

The faces of the Canadian art world were chosen by virtue of "their recognized authority." The figures are "critical countenances" because 'what they countenance is what counts as art in this country today.' Also, says Townsend-Gault (p.55 catalogue): "It reflects a mainstream, centrist, still essentially WASP establishment."

MacKay considers everyone he has painted in his trans-Canada scroll a peer: Michael Snow, Brenda Wallace, Bruce Parsons, Max Dean, Alan Wood, Melvin Charney, Jean Borsa, Mira Godard, Dennis Reid, Edythe Goodridge, Alf Bogusky, Doris Shadbolt, Liz Magor, Gerald Ferguson, Ian Wallace, Carroll Moppett, Diana Nemeroff, Eric Fischl, Doug Bentham, Mark Holton, Jeff Spalding, David Craig etc., etc. Hundreds of face-feet worth of comfortably powerful art figures are included.

It is debatable whether the MacKay/Townsend-Gault project constitutes a variety of official portraiture (obviously, it has not been commissioned). Nevertheless, we have a wealth of imagery with which to compare and contrast Some Critical Countenances.

As a slightly 'off-the-wall' example, Elizabethian court portraits position a tiny face on top of an extraordinary body of raiment -- a raiment of authority. By contrast, MacKay shows whisps of clothing around enormous faces (most often whisps of the small-'a' academic tradition of bad dressing which gives away the sitters' connections to the rumpled authority of The Professor).

Fantin-Latour's 19th Century portraits of his artist and critic friends, including Manet, Baudelaire, and others, might be a more fitting comparison, since those paintings were made as self-consciously promotional pieces, though MacKay's painting is hardly any more a vehicle of personal self-promotion than any other exhibition - MacKay's painting does not have the same sense of ideological coherence as Fantin-Latour, who promoted his friends against a much more clearly defined establishment.

The determination of the sequence of characters in his frieze is random, so we cannot read a left-to-right sequence of the most or least powerful people, for example, or a west-to-east layout: some of the paintings-within-a-painting were false starts, abandoned half-finished. All were made in an illustrative style based on projected slides, and painted in cramped conditions; there could have been others included who were not included, but a natural time limit on the project was forced by the upcoming date at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

The work suggests a panopticon of bureaucratic personalities supervising art production with an individual gaze. MacKay and Townsend-Gault look at the faces, the faces look at grant applications, the faces look at the pictures they produce, their neighbors, the absent others, the camera...

Townsend-Gault's 1988 Art History article "Symbolic Facades: Official Portraits In British Institutions Since 1920" prefigures issues of the MacKay/Townsend-Gault collaboration:

"The portraits are controlled, at all stages of their realization, by the institution..." (Art History, Dec. 1988, p.512)

and

"...within the specific institutional context for which they were intended and to which all contribute, they endorse it; without, they lose their power, their meaning." (p.514)

and,

In order to justify the claim that these portraits should be seen as images of social control rather than of individuals, it is suggested that certain aspects of the history of portraiture, psychology, body language and reception have survived in an attenuated or re-contextualised form in the genre. They are the conventions, observed by the artists and expected by the endorsing institution to symbolize its explicit attributes and implicit ideology. (p.514)

The conventions of official portraiture discussed by Townsend-Gault in her essay on the British tradition suggests directions for assessment of the MacKay/Townsend-Gault project. The weight of history and tradition and authority have not had much of an opportunity to bear down too heavily on most of the faces portrayed here. Also, we are looking at a set of institutions in Canada - and a society - which has an ambivalence about figures of authority. Across MacKay's panorama, few figures demand unequivocal acknowledgement as embodiments of artistic authority - most would themselves straightaway deny many of the positions of authority we think they have. Do any of the people depicted in this work have more power over a 'community' than a successful car dealer has over his? I doubt it. But however small the authority, beware its object.

Again, the informality of these paintings as official portraits of movers and shakers in the Canadian art world tells us something about the general informality, or perhaps the ideology of informality, under which the Canadian art world operates. Every one of these people is a bureaucrat of some sort (I like to use this word in a very positive way: their power is quite limited.)

MacKay has supplied the face to the faceless bureaucrat in the form of the giant face of a mother hovering over her child, or the big spectacle face given the moviegoer in the darkened theater, or (more appropriately) the faces of negotiation at close quarters in which art world people schmooze:one can imagine these faces exchanging polities across a desk (at which artists can be on either side.) This knowledge - the knowledge of the face -is invaluable to the supplicant in a bureaucratic system: as you enter the lobby of the funding agency, or the gallery, or as you approach the loft of the artist , or the favourite bar of the gallery worker, you must have a clear idea about the authority of the signature of the person you are approaching, and a clear idea about what they look like, so as not to confuse them with a similarly-clad bicycle courier.

We know that the bicycle courier may be an artist, that the curator may also be a critic, that the curator/critic can be the artist, that the art-applicant may become the authority (we get this in remembrances of the past lives of some of the artists shown in the work: they too had to struggle through the system, several struggle still). Identities are slippery things in the art world.

|

|