Click here to return to the first

Richard Williams' page.

Click here to view images

of Richard Williams' work.

Click here to read an essay

by Meeka Walsh.

Click here to read an essay

by Cliff Eyland.

Click here to read a 1986

essay by Dale Amundson.

Click here to read a 1996

essay by George Swinton.

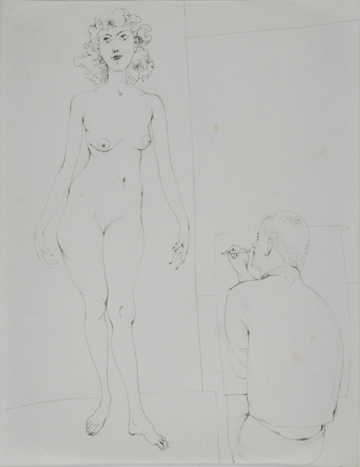

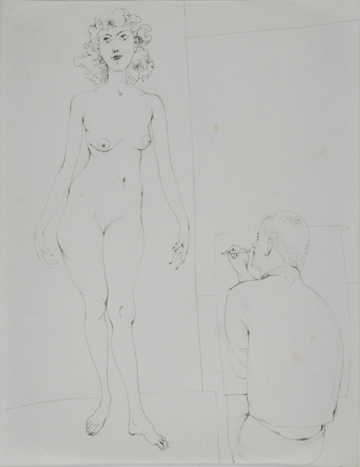

Richard Williams: An untitled, undated graphite on paper study. Collection of Gallery One One One; gift of the artist.

Richard Williams interview by Cliff Eyland.

CE: Do you approve of life drawing?

RW: Definitely. I feel that it is the structural support for almost any kind of drawing. Many ideas that we have about proportion come from the figure. The way things join together and move mechanically comes from the figure and certainly our concept of beauty comes from the figure. I think that the changes in art school curricula that eliminate life drawing are a mistake. Whether or not your art form has as its subject the human figure I think it still provides a reference and a kind of discipline for aesthetic thinking.

CE: When did you start life drawing?

RW: Drawing from a nude model didn’t start for me until about the last week of my freshman year at Carnegie Tech.

That was in 1940 and I would have been 18 or 19 years of age. I remember being very disappointed that during our whole first year we were allowed only 3 hours of drawing from life. I had been trying since I was 9 or 10 to draw nude figures using only an imagination that was woefully short of information, and I thought “Now that I am in art school all the mysteries will be revealed, undoubtedly drawing the human body will be the first thing they will teach me.” Instead, almost all of our first year was devoted to learning to draw objects, some simple and some complex, in perspective, free hand. Still life was the subject and either pencil or charcoal the medium. We learned to think of objects as geometric solids no part of which could exist in another object’s space. Only after all objects were comfortable in a given volume of space was it worthwhile drawing their natural contours and rendering their surface textures. We had research problems that extended our reach. They included learning to read ground plans and elevations in order to draw a building or an interior with furnishings in perspective and to scale. I remember that our research of textures included rendering human hair, a 3-hour project; but our 3 hours with a female model seemed to have no purpose or desired end other than to enable us to say we’d been there. Don’t misunderstand I treasure the content of that first year, which by the way, included a design course. I return to those basics every time I pick up a pencil or a brush, and while I was teaching here at Manitoba I managed to pass many of them on to my students; but I had them drawing the nude model well before the end of their first term! As for my own life drawing education, that came on strong along with life modeling in 2nd year. Both of these continued in 3rd and 4th years with courses in Anatomy and Figure Construction added. Perhaps I should remind you that we were in a course of studies that led to a Bachelors degree, so there was also heavy academic content required: Art History, English, French, History of Architecture, and a battery of electives of which I took Psychology and Philosophy. Also, since there was a World War brewing and all male students were eligible for the Draft, we were obliged to keep fit, to which end physical education was required in all our 4 years. I had a full schedule of classes, a full school week to which I added 5 or 10 hours of work on Saturdays or evenings to help meet expenses. Fortunately I could live at home which kept me well housed and fed but required a 2 hour commute every day. So it was with some effort I was able to stay on the honour roll and keep my scholarship. I remember struggling to get up in the morning, and riding the trolley with my eyes closed to catch up on my sleep, but I loved it.

CE: Did you see the Carnegie Internationals regularly?

RW: Yes, indeed! The Internationals were always an important event in Pittsburgh. High schools took their students on field trips to the Carnegie Institute regularly and ours in Dormont was no exception. When I was a student at Carnegie Tech I continued to visit regularly. I saw my first Cubist painting there, it was a still life by Braque, I think it was called The Yellow Table Cloth. Either it had won a prize or the Carnegie Institute wanted to buy it. This caused a great controversy in as much as the cubist painting was meaningless to the general public. I remember enjoying Roualt’s Old King which I know Carnegie did buy. I saw my first Dali at one of the Internationals, I think it was The Persistence of Memory. But in the late 30’s and early 40’s not everything in an International was representative of a post – 1912 European style or was some adaptation of it: For instance my sister who was 11 years my senior and had never heard of surrealism could always find a conventional portrait of some important person to admire and would always give full marks to the one she thought had the most beautifully painted hands. There seemed to be something for everybody and it was always the best of its kind. In addition to portraiture they had included landscapes, seascapes, interiors, exteriors, figure compositions, still lifes, city scapes – all of these the best that were available in that geographic territory covered by the International.

CE: What did you do after graduation?

RW: After I graduated from Carnegie in 1943 (note: The Carnegie Institute of Technology is now called Carnegie Mellon University and counts Andy Warhol and Philip Pearlstein among its graduates) I went into the Army. The summer before that I had joined the Army Reserve so that I could finish the final year of my degree program. As soon as I graduated – in late May or early June – I reported to the induction center at Fort Meade in Baltimore.

There they put us through various aptitude tests. They discovered that I had some mechanical ability, so they sent me to aircraft mechanics school in Biloxi, Mississippi. That’s where I learned to take care of B-24 bombers, called ‘flying boxcars”. While I was in school it was decided that I was best at electrical things so they made me an aircraft electrician.

My first posting was to Lincoln, Nebraska, an Air Force staging area. What that meant was that after the combat aircrews had picked up their airplanes from the manufacturers in California they had to fly them to our base for some modifications. It was there that the aircrews got acquainted with their airplanes and personalized them by giving them names and many wanted also to have a mascot painted on the nose of their bombers. It got around that I was an artist and was willing to paint their airplanes in my spare time. This was by no means an official duty but something that was arranged between a crew and me.

When the war in Europe started to wind down fewer combat crews were sent in that direction, however replacement aircraft flown by ferry pilots were needed and they still had to stop at our base for modifications. My commanding officer was familiar with my work and when one of these was left on our tarmac without any forwarding address he thought this was a wonderful opportunity to pay his young wife a great compliment by naming the bomber after her. He asked me to paint her name under a figure with a face resembling hers and dressed only in panties and bra. However when his wife saw what we had done she was not amused she said, “ How would you like to have a picture of you in your underwear flown all over Europe?” He ordered me to remove the painting and leave only her name. That took a lot of turpentine! By way of compensation he allowed me to use an unoccupied parachute loft as a studio for my own work. I did some interesting stuff in that studio. In fact the Gallery One One One collection has an unfinished self-portrait in my fatigues that was done there. The first Annunciation that I ever did was painted there. When I sent it home to Pittsburgh it went into the annual exhibition of the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh (February 13 – March 11 1946) at the Carnegie Institute where it was chosen to serve as a memorial to Harvey Gaul a well known choir director, to be installed in the Carnegie Library.

CE: What happened after the war, after the army?

RW: When I got out of the army I went back to Pittsburgh and reclaimed my old bedroom/studio in my parent’s attic. The GI bill for veterans in the US provided a variety of benefits to help us to re-enter civilian life. One of these was a monthly stipend for a person to go into business for himself, so for that summer at least I decided to be a professional artist. My career had not suffered in my absence since I had left a number of paintings with my brother to be entered in a number of exhibitions. Some of these had won prizes and had received good notices in the Pittsburgh publications.

Fairly early in the summer I received a telephone call from Jim McDonough, the head of the Fine Arts Department of the Georgia State College for Women in Milledgeville, Georgia. He was born in Pittsburgh and was very familiar with the Carnegie Tech Fine Arts program, I think he had studied Architecture and the History of Architecture there. So he naturally turned to Tech when he needed to replace a member of his department in Georgia. At that time I had a piece in the annual Summer Exhibition of Paintings by Pittsburgh artists, organized and shown by The Carnegie Institute and had been singled out for special mention in a newspaper review of the show. When he inquired at the Painting and Design department at Carnegie Tech about suitable candidates for his vacant position one of the faculty directed him to that review and recommended me for the job. He interviewed me and hired me. Although I was having some success with my business I decided to take the job. I thought I would give teaching a try for at least a year. Later that summer, before I left Pittsburgh for Milledgeville, Homer St. Gaudens, Director of the Carnegie Museum of Art visited my studio to choose a painting for his 1946 Painting in the United States. This exhibition was, I believe, the last of a series that he had begun as an annual replacement of his Internationals when the war in Europe had made them impossible to organize. He chose The Whirl that is now a part of the Gallery One One One Permanent Collection. [Note: The exhibition included works by Georgia O’Keeffe, Salvador Dali, Jack Levine, Charles Sheeler, Rockwell Kent, Edward Hopper, John Sloan, Stuart Davis, Lyonel Feininger, Ben Shahn, Joseph Stella, Andrew Wyeth, Max Ernst, Paul Cadmus, Walter Kuhn, Reginald Marsh, Arthur Dove, Thomas H. Benton, John Marin, Bradley Walker Tomlin, Dorothea Tanning and Charles Burchfield.]

I enjoyed my first year of teaching at Georgia state College for women very much and during that year I decided to become engaged to a young woman I had met while I was stationed in Topeka, Kansas. I felt we would have a more secure future if I became a teacher. We were married at the end of that first year, and I was encouraged to stay on another 3 years. Toward the end of that period Jim finished his dissertation for a doctorate at Princeton and accepted a position at a Florida University. It was then that he told me that if I wanted a career in University teaching my Bachelors degree was not enough - I would need to get a graduate degree in Fine Art. So the two of us looked at university calendars and mutually decided that the State University of Iowa would best satisfy my needs.

The Iowa calendar said that one could earn a Master of Arts degree in as little as one year and a summer, if one wanted a Master of Fine Arts at least two further years of study would be necessary. So I asked my Dean for leave of absence to complete an MFA. He told me that he could give me a leave of one year with half pay, if I wanted an additional year it would have to be without pay. Fortunately I had the GI Bill to draw upon for fees and subsistence in addition to some savings. Also my wife was working as an academic secretary for the Department of Home Economics at Georgia State College for Women and we hoped she could get a similar job in Iowa, so I took a provisional two years off determined to finish an MA in one year and to push on and complete the MFA in the second year with summer work. To this end I signed up for a full year of Art History which much to my surprise I loved. Toward the end of the year I had an interview with Lester Longman the head of the school and with William Heckshire my History advisor, and although I had made a start on the research for my MA thesis they both insisted that the degree was impossible in the time allowed and instead I was advised to apply the art history credits to the MFA degree and make that degree my target. I reported to my Dean at Milledgeville that I needed the second year and was told that my job would still be waiting for me. Now all I had to decide was in which studio subject I would major. I had been working of course as an artist in Sculpture and Painting but the student work at Iowa that looked most interesting was in Printmaking so I enrolled in all three fields. After the first six weeks it was obvious that my heart belonged to Printmaking and I was welcomed into the field by Mauricio Lasansky the professor in charge of the area. I dropped the subject I had been pursuing for an MA and switched to research in the history of Intaglio printmaking.

CE: So you were making art and doing academic research related to your work at the same time?

RW: Yes. Then in the 1952 – 53 school year while I was still enrolled at Iowa I began checking the Director’s notice board, keeping track of job openings for university teachers. This had become necessary because when I had informed my Dean at Milledgeville of my decision to continue at Iowa after my second year, he told me he could not guarantee that there would be a position for me to return to. Enrolment had declined throughout the system, funds were being cut and it was likely that my position would become a casualty of this austerity. So here I was checking “want ads”. Those for U.S. institutions did not look very attractive, nevertheless I did go for one or two interviews, but neither the interviewers nor I were favourably impressed. There was one notice at that time from far away, a frigid place called Winnipeg, Canada. Longman thought I might be interested because it was for an Assistant Professorship in a University school of art, small but resembling Iowa’s and its director as well as two of his faculty were Iowa graduates.

My wife was pregnant and would have to stop working soon, my GI Bill would not buy me another full year of study, I had more credits than I needed for an MFA, and in fact was well on my way to a Ph.D. in Art History, but I still wanted to do some revising of the written MFA thesis, and quite frankly, I was having the time of my life continuing my printmaking on large copper plates and experimenting with welded sculpture, using steel rods, scrap plate and found objects. Besides, Canada was a foreign country. What to do? After talking it over, my wife and I decided that drawing upon our own resources, we could afford another year, and Longman said, if needs be, that he could find something for me in Fine Arts, and that he had been thinking of offering me a job in his faculty if I wanted to stay and finish a doctorate in Art History. So I didn’t apply for the job in Winnipeg.

CE: So was your art primarily printmaking then?

RW: Yes.

CE: Did that involve figure drawings?

RW: Yes, there were figures in the prints and from time to time I used a model when I drew them, but the last year or so I was drawing from my imagination.

CE: Figurative things?

RW: Yes.

CE: When did you come to Manitoba then, and what brought you here?

RW: I came to Winnipeg in September 1954 in response to a notice Longman received from The University of Manitoba early in the 1953 – 54 school year. This time they were advertising two vacancies: one for the position of Director: the other for an instructor in painting and printmaking. Longman asked me if I was interested in either of these. I said "Yes, definitely. The director’s position interests me especially." He said he would send them his recommendations accordingly. Some months later there was a communication from Bill McCloy, Director of The University of Manitoba School of Art, saying that he had received my name from Longman, but no application from me – was I interested? I answered in the affirmative and sent him an application immediately. He was favourably impressed and told me he had resigned his position in order to accept one at a Women’s College in Connecticut. He intended to spend the summer in Iowa City finishing his PhD and searching for someone to replace himself at Winnipeg. He had already hired somebody for the other position ( I discovered later the other person was George Swinton). While he was in Iowa he also wanted to interview me. We met several times that summer and he told me quite a lot about Winnipeg and the School. It sounded like quite a challenging job, not the kind my ambitions as an artist expected to meet but I had some thoughts about what I might bring to the school and to the community, so when he offered I accepted. But the offer had to be approved by the Dean of Arts and Science who at that time was The Academic Head of Fine Art as well. I had to go to Winnipeg for an interview. I spent the better part of a day with Dean Waines. Then at mid-afternoon, he turned me over to Dick Bowman who had been McCloy’s most celebrated artist and would have been the only remaining Iowa grad on the school staff except that he was packing and about to move to California. Nevertheless he showed me around the school which at that time occupied the 2nd and 3rd floors of the old Law Courts building on Kennedy St. in downtown Winnipeg. I was impressed with the building, the stained glass windows, and wide staircase from the 1st floor up to our 2nd floor, the decaying grandeur of the drawing and painting studios, the romantic character of the attic-like 3rd. floor. The Art Student’s Club rented a space downtown to hold a farewell party for Bowman and a previewing of me. They were lively and friendly. I remember Don Reichert and Mary Thorpe, both second-year students at that time. I believe Don was an officer in the club and Mary was his girl friend.

The next morning, after breakfast at the Fort Garry Hotel, Dean Waines offered me the job at the rank of Assoc. Professor and $2000 more than I had been paid in Georgia and I accepted with an understanding that I would advance to Full Professor and another $1000 in pay depending on how well I performed in the first year. That afternoon Bowman introduced me to various people that he and McCloy knew socially in the city and in the University. After dinner with a professor from The School of Architecture who was getting ready to move to Vancouver, I left for Iowa City.

CE: What did you agree to teach at the U of M?

RW: Well, after meeting with George Swinton over a few drinks we swapped a couple of courses. Bowman’s position, which George had inherited included the teaching of Printmaking, McCloy’s position included the teaching of Fundamentals of Drawing. I wanted to teach what I had specialized in at Iowa, so I traded the Drawing course for his Printmaking. Each required 3 hours of teaching 3 days a week. The rest of my load consisted of:

1. Introduction to Art- 1 hour lecture 3 times a week (every first year student in both the diploma and the degree program had to take this).

2. Principles of Art Criticism – 3 hours lecture 3 days a week (every 3rd. year student had to take this).

3. An evening non-credit drawing and painting class for adults- 2 hours studio 2 times a week.

4. A Saturday morning class for junior and senior high school students – 2 hours studio once a week.

In total, including the 9 hours of printmaking I had a load of 21 contact hours. In addition to this I ran the School with a half-time secretary and one of my teachers as the Registrar for evening and Saturday morning classes. The Saturday morning and lecture classes required considerable preparation. While I knew the material well enough I had never taught these courses, so I had to design them as I went along, with some help from an outline prepared by Longman for one of his courses.

CE: That’s a very heavy load. How did you do it?

RW: Well, I gave up the evening course after one year. We had student assistants for Saturday morning classes and some of mine were very good. Jack Sures was one of them.

CE: When did you find time to do your own work?

RW: For the most part I had to give it up. I continued to exhibit however using things done earlier but seldom or never shown in the U.S. I thought my painting and printmaking was not as important as the School and our students and how they related to the community of Canadian artists and to the public, so I decided to devote the next few years to helping in whatever way I could to make improvements in those areas.

My first year in Winnipeg was spent getting acquainted. I could see that McCloy had accomplished much during his 4 –year term. He had designed and established a BFA degree program that was second to none. It offered 6 major studio subjects provided by 6 instructors to 60 degree and diploma students. The work they had produced in my major subject, printmaking, was remarkably sophisticated but tended to be mostly derivative of work they had seen in their text books. McCloy had told me with great pride that the work of his staff and their students was the most modern in Canada. I was not surprised then to see these derivations since modernity had been their aim. But it made me decide to emphasize to my students and staff the importance of findings ways of working that stamp everything you do with your own trademark. Visual art, like music is a language of emotions, it articulates our feelings. The style or idiom you use must be found within the expressive intention, not chosen because it’s the “latest thing”. This doesn’t mean that you must invent something like Picasso’s Cubism that changes the face of art for the next five decades, but rather that you might use his plastic space if the tension between its apparent literalness and its inherent instability seems to help to express feelings you hope to arouse in the viewer. At any rate, I didn’t want for us to have a “house- style” which I felt McCloy’s pursuit of Modernism could engender.

McCloy had tried to show work by his students and staff in the annual exhibitions of the Manitoba Society of Artists at the WAG, but this conservative group usually eliminated them for “ lack of space”. The Women’s Committee of the WAG had annual exhibitions at the gallery at which they sold Canadian artists work they had seen and liked during their travels. McCloy found the women sympathetic to his cause and rather than ask the WAG Board to honour their sister institution (the Gallery and the School were created together in 1913, and shared the same charter) He proposed that the Women’s committee change their exhibition to a non- juried show open to all Canadian artists in collaboration with the Art Student’s Club the members of which would be responsible for the physical work entailed. Eckhardt and his staff were minimally involved. Staff and students of the School finally would be exhibited. McCloy thought of the whole thing as a "Salon des Refuses" - the Manitoba Society of Artists being the "Official" salon.

Results hardly made the effort worthwhile. Yes, the school was well represented and a few conservative artists of some standing sent work, but it was predominately made up of Sunday painters getting wet for the first time, nothing to excite anyone. When the co-sponsors asked me I told them that we had not seen any professional art from outside Winnipeg since I came, and at this rate it looked like I never would. They needed a different kind of exhibition if they wanted the work to come to them. First: a jury from outside Winnipeg made up of people trained to recognize quality and who had the respect and trust of the professional community. Second: substantial cash prizes and gallery purchase prizes. Third: efficient handling of negotiations with artists. Fourth: good publicity before, during, and after the show. I gave them my whole plan for the Winnipeg Show. I told them how to do it and I asked George Swinton to help them. Virginia Berry and I wrote the prospectus that was sent to artists. I even wrote a charge to the jury that they said was the best they had ever seen. Our student’s and staff submitted work to the jury. Some of them were accepted and they looked very much at home there among their contemporaries from the rest of Canada, many of whom either were current stars or were about to became stars in the future. The show was a success and when the controversy following the resignation of a Women’s Committee member was reported in the media across the country, the Winnipeg Show became known as the most prestigious exhibition in the country. It remained at the top of the heap until the 1968. That year CARFAC [Canadian Artists Representation] held their annual meeting in Winnipeg with the result that a team of its officers approached the Winnipeg Show sponsors demanding that they meet CARFAC’s newly ratified conditions, including no entry fees, artist fees and prepaid return shipping for all accepted works. Commendable as these conditions may be when dealing with established artists, they were inappropriate for the Winnipeg Show which had become largely a young artists’ exhibition and sale --a coming of age. Paying them for the privilege of discovering them and possibly selling them seemed out of the question. The Womens Committee were volunteers and in no way self-serving like the Art Students Club. Their whole reason for being was to promote public awareness of art and to help the gallery to grow as a significant educational institution. To this end their purchase prizes were put to the Gallery’s collection, which would help illuminate the early history of contemporary Canadian art. CARFAC’s conditions would in themselves exhaust the budget that the Womens Committee had managed to earn each year. CARFAC was adamant, and the Committee chose to end the series and turn their attention to other projects rather than do battle with those they had wanted to help.

In 1956, the year after the Winnipeg Show was begun, I designed the steel studio furniture that is still used at the school. George Swinton had reported to me that his easels were ancient sticks of wood held together by a few brass hinges. There were only two serviceable painting tables, and his wooden drawing donkeys were rickety and weighed a ton. After consulting with him as to what functions they had to serve, I designed the nesting easels, stacking tables, and stacking drawing donkeys. George was delighted.

In 1958 Jack Russel and I approached president Saunderson with the idea of sponsoring a University Festival of the Arts, and managed to get his permission to offer such a festival each year. He also provided us with a small budget. Through the years we were able to bring to our campus such luminaries as Laurens van der Post, Sir Herbert Read, Sir Basil Spence, Steven Spender, Harold Rosenberg, Irving Layton and John Cage. This faculty - run festival continued until the late 1960’s, when involved university personnel underwent considerable change.

I was one of the founding members of the University Art Association of Canada, along with 6 or 7 heads of other University art departments and schools.

I was regional representative for the Western Canadian Art Circuit that organized and circulated art exhibitions among the smaller galleries throughout the West.

Also, I served on the board of the Winnipeg Art Gallery from 1956-1977, which covers among other things the period when the present art gallery was conceived, planned and built.

In addition to these and other things too numerous to mention I did do some art of my own; I created two large pieces of sculpture for Polo Park shopping mall in Winnipeg when it was first erected in 1960. Both of these pieces were destroyed subsequently. I also did another commission for an architectural project – the Investors Syndicate building on Broadway Ave. in Winnipeg. I have no idea what happened to that sculpture piece since the building was renovated in 1964.

I also found time - usually in the evenings or weekends to paint a half-dozen portraits of deans of the faculty of engineering from the University of Manitoba, as they retired, or died. These were done about one every four years. My own work continued without interruption from about 1957 onward. During the late evenings and early morning hours, when all other demands of the school had been finished, I would draw. This was a never-ending series of drawings, usually of the nude. I would make drawing after drawing on letter-size writing paper. Often I had had a model for my printmaking class or my Saturday morning class who I had posed, but who I had not drawn along with the class. At home at night I would draw various aspects of that model from memory.

CE: So the drawing was on the sly?

RW: Pretty much.

CE: So you had to wait for a sabbatical to get some of your art made?

RW: Yes, and I didn’t take a sabbatical until 1969 when I was awarded a Canada Council grant to travel in Europe and to do some sculpture and drawing in a studio I had just added to my home. That was a wonderful experience, seeing Europe for the fist time, which I did for 2 months. When I returned to my studio in Winnipeg I did a series of sculptural figures in direct plaster. I also took a commission to paint a portrait of the retiring Head of Pediatrics, Childrens Hospital, Winnipeg. I then returned to drawing.

George Swinton, some of our students, and I began hiring a model to pose for us, using one of our School studios about once a week. The rest of that sabbatical year I drew with this group regularly. I also made in my own studio a number of highly finished drawings that were strictly from imagination. I was able to exhibit some of these at a large group exhibition at the Winnipeg Centennial Concert Hall and to sell several of them.

After that year of being an artist it was very difficult to return to the school as the Director. I decided I would resign at the earliest opportunity. In the meantime I wanted to hire a Ph.D Art Historian who could develop a major in Art History. I also had a salary for a photographer who could do the same thing for a major in photography. All the groundwork had been done in preparation for these developments, but I was not able to find suitable candidates for the two positions. When I stepped down as Director and joined the teaching faculty they were left for my successor, Al Hammer, to fill.

I had a second sabbatical in 1976-77. I was working on lightweight sculpture that resembled kites. These were intended to float in space changing their identities as they were turned by light breezes. The work was somewhat interrupted. There were important changes in my life. My first wife and I were divorced and Pauline and I were married. Relocating in itself created major interruptions and adjustments. My work never regained its full momentum until 1984 when I was granted a study leave to work on some abstractions that employed optical illusions, shifting perspectives and other devices that were intended to confuse and hopefully enchant the viewer. After finishing one I decided that I really didn’t want to continue in that direction. What I really wanted to do was to make paintings that included the human figure in various situations that made use of some of the same devices as the intended abstractions. I chose the Christian Annunciation because it was one of the great mysteries of the Gospels and offered opportunities to meet my other conditions. Besides I had to try to explain such mysteries to myself and through my paintings perhaps make them relevant to the viewer. I thought that I might accomplish this end by making a half dozen or so paintings and drawings that I could show at the end of the study leave. Actually this project took 10 years and produced approximately 50 works. The last one which, Flesh and Blood, was completed in 1994. The exhibition Flesh and Blood- the Art of Remythologizing, happened Nov. 8 – 1996 and was curated by George Swinton for Gallery One One One.

CE: What about the life drawing related to the Annunciation series?

RW: Usually I would make a rough or fairly elaborate sketch of the idea, then I would get a model to pose, photograph him or her with a Polaroid camera and then proceed to enlarge it freehand onto the canvas, but some were completely invented.

CE: Is there a difference for you between inventing a figure and drawing a figure from life or a photograph? You’re so good at drawing that the results seem interchangeable. Why can’t a viewer tell what is invented and what’s drawn from life or a photograph?

RW: When I work from a photograph I do a certain amount of inventing to get a little bit more of a rhythm between the figures or a more vital kind of pose than the model had given me. I work until the figure seems to say what I want it to say - until it has the right body language. Certain details are there in a model, but you can modify them. I use tear sheets a lot - things from periodicals. Usually I use them to do joints for example and to get right the way a shoulder fits. I might find something in a newspaper or magazine, but the personalities in the drawing are not usually picked up that way.

CE: Is it the personality that you make up then?

RW: Yes, that’s pure invention. When I was going to Carnegie in Pittsburgh, I travelled by streetcar from my home to the campus and I would look at the other passengers and draw them surreptitiously. Many of my sketchbooks at that time were filled with these drawings. I learned a lot about types that become personalized by a situation. Also when I was at Iowa I began a research paper on the History of Physiognomy which I thought would be an appropriate study for a masters thesis, but I discontinued it at the end of my first year.

We used to do caricatures at Carnegie. I had a professor named Russell Hyde, who put us through a course that dealt with this subject; actually his aim was to develop our skills in drawing characterizations not caricatures. When I taught my first year drawing classes here at Manitoba, I put my students through something similar. I would have them form a circle with their drawing donkeys in order to draw each other. They were not to be afraid of making caricatures. It was all connected to gesture drawing - the gesture of a face.

CE: Is the gesture of a face best accomplished with quick drawing?

RW: I don’t know how to answer that, but that’s the way I approached teaching it. I don’t know if Nicolaides [Note: the author of The Natural Way to Draw] would approve of that. Also at Carnegie Tech the departmental office would often receive requests for an artist to take on some particular job either on campus or in town. One type of job that a friend of mine and I were usually called upon to do was to draw quick portraits of guests at fraternity parties. We tried not to make them caricatures and had a lot of experience doing quick portraits that I always hoped would reveal the sitters personality. When I decided to do the Block Party project my intention was to create such characterizations. I would usually begin with a type of figure and face and then push it until I thought my friends would be able to say, “I think I know that fellow”.

The Richard Williams

CD-ROM includes information about other Gallery One One One projects: Gallery One One One, School of Art, Main Floor, FitzGerald Building, University of Manitoba Fort Garry campus, Winnipeg, MB, CANADA R3T 2N2. Gallery Hours: Noon to 4 PM (weekdays only).

TEL:204 474-9322 FAX:474-7605

For information please contact Robert Epp

eppr@ms.umanitoba.ca

|

|