WALLENBERG COUNTRY

[First published in a brochure to accompany an exhibition of Eyland paintings with Joseph Sherman poems curated by Terry Graff for the Confederation Centre Art Gallery & Museum in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island in 1998. This first exhibition of this ongoing project is now part of the Confederation Centre's permanent collection. ]

As a child in the late 1950s and early 1960s, I lived in West Germany. My father was in the Canadian Air Force, which was part of the Allied occupation. According to my mother and father, the Germans were anxious to forget the War, and perhaps not surprisingly, no German they ever met admitted any involvement in Nazism to them.

In 1988 I participated in an exchange exhibition which involved artists from Halifax, Canada and Lublin, Poland. The political focus at the time was not on World War II, of course, but on Poland's recent emergence from communism. Given the political awareness of many of the Canadian and Polish artists in the Halifax/Lublin show, however, I found it strange that none of them--including myself--felt they had any reason to remind anybody that the Lublin region was the Holocaust's dead centre. Perhaps the historical forgetting is understandable.

I lived in Cambridge, England in 1992 as the Yugoslavian situation exploded and the term "ethnic cleansing" was coined. It was getting close to a half century since the end of the War and Nazism was again on the rise in Europe: fascism seemed on the verge of a big revival. The defeat of communist dictators was being trumpeted by the neo-conservative press in glowing allegories of free markets and plenty. The remnants of history were being mopped up. Such euphoric fantasies dominated public discourse.

Clearly it was a time for some active remembering, and there were no excuses for me this time. But how does one best remember as an artist? In the intellectual world of 1992, post-structuralism and deconstruction were beginning to be criticized for their deleterious effects on the academic practice of history. If, for example, texts are infinitely mutable, how might records of the Holocaust be believed once an elderly generation of survivors were gone? Strong people can insist on the truth of their experience with living breath, but these strong people were fast disappearing.

Artistic problems about remembrance seemed to converge in me in England in 1992. These were the sparks: Joe's Wallenberg book, my perception of a crisis in cultural theory, the neo-conservative political climate, and most of all, my acute awareness that I lived within driving distance, at least as Canadians reckon it, of Bosnia, were genocidal strong men were doing their business with impunity.

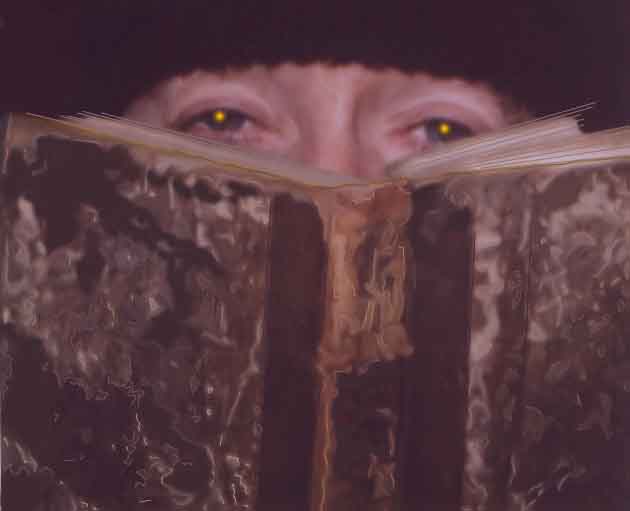

I got copies of Primo Levi's books and Martin Gilbert's chronicle of the Holocaust from one of the Cambridge book stores, and I read them carefully. I read Joe's book carefully, too, because I felt that his retelling the facts through poetry was very clever. Sherman is right in implying that Wallenberg has to be "imagined" by a new generation, just as Gilbert was right to have soberly and methodically provided the facts so that such imaginings could be made by people like Joe and myself, who were not witnesses.

I wanted to put Joe's poetry and my paintings together. I made new paintings, and I chose paintings from my past work which I thought could be, as Joe put it, "a gloss" on his book and on Wallenberg's life.

Only one or two of the Wallenberg paintings has been made from a model or visual source of any kind. In the past few years most of my paintings appear to me as I make them: in a way I watch them being made. These are not conventional illustrations, because they resist certain kinds of closure in relation to the poems. They run parallel to Joe's Wallenberg poems with no one-to-one connection.

|

|