Doménica Naranjo

Advisor: Carlos Rueda

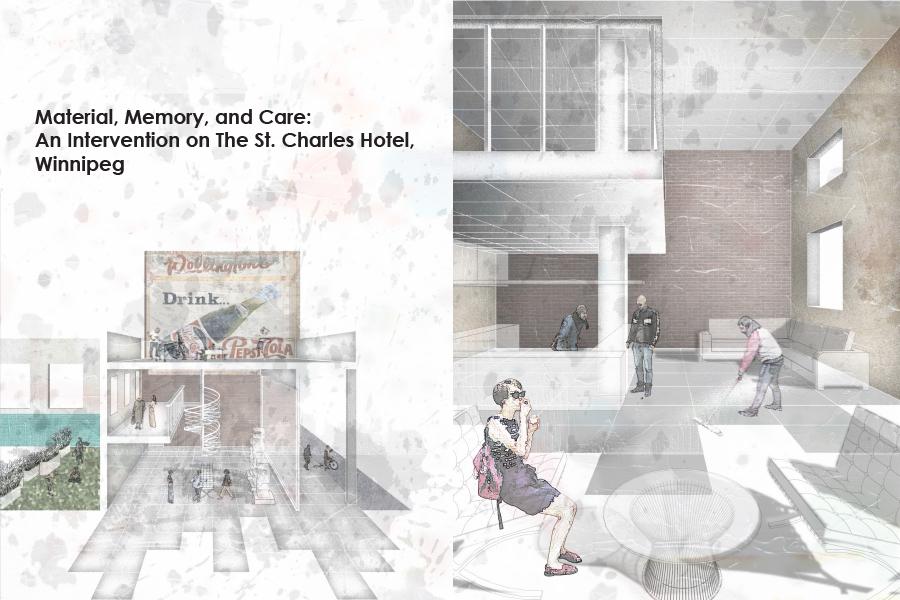

Material, Memory, and Care: An Intervention on The St. Charles Hotel, Winnipeg

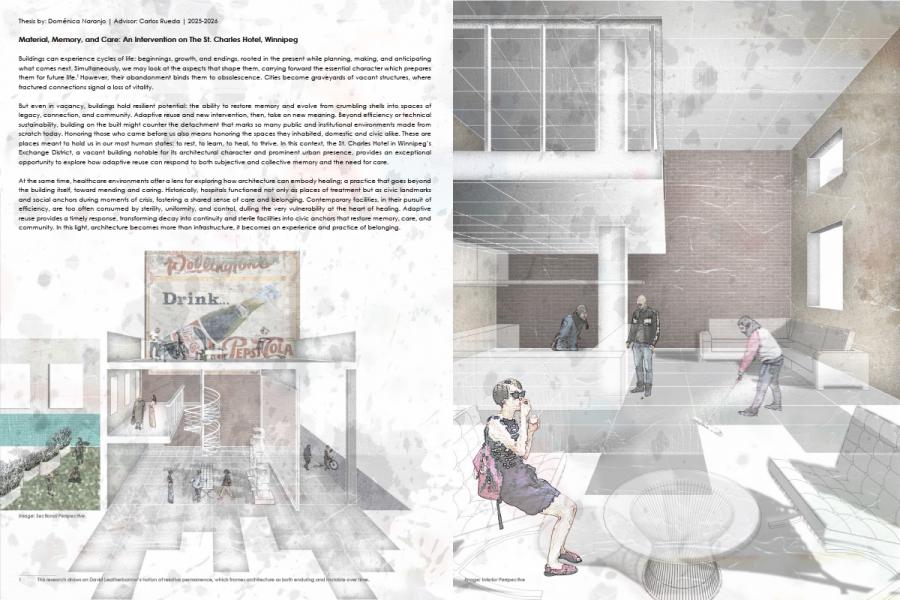

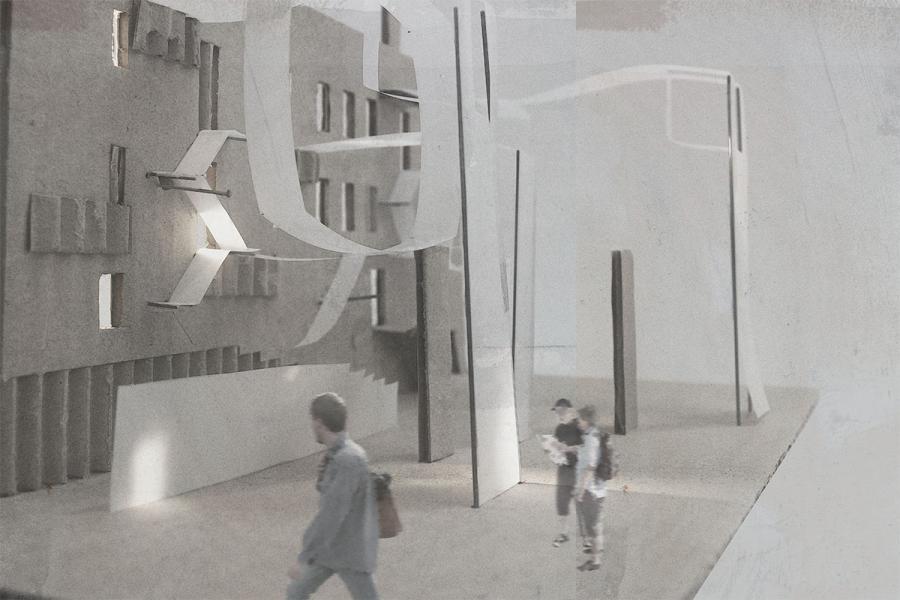

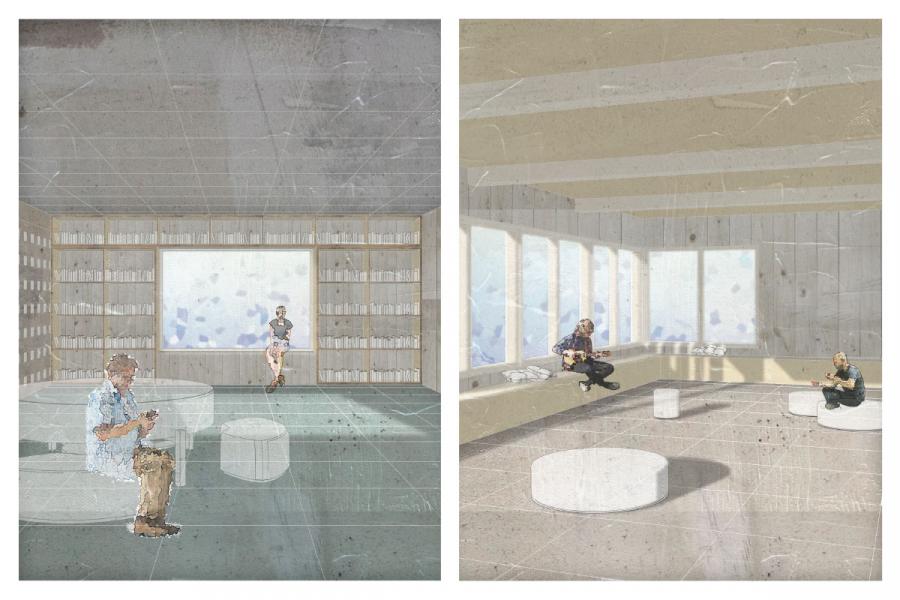

Buildings can experience cycles of life: beginnings, growth, and endings, rooted in the present while planning, making, and anticipating what comes next. Simultaneously, we may look at the aspects that shape them, carrying forward the essential character which prepares them for future life.1 However, their abandonment binds them to obsolescence. Cities become graveyards of vacant structures, where fractured connections signal a loss of vitality. But even in vacancy, buildings hold resilient potential: the ability to restore memory and evolve from crumbling shells into spaces of legacy, connection, and community. Adaptive reuse and new intervention, then, take on new meaning. Beyond efficiency or technical sustainability, building on the built might counter the detachment that marks so many public and institutional environments made from scratch today. Honoring those who came before us also means honoring the spaces they inhabited, domestic and civic alike. These are places meant to hold us in our most human states: to rest, to learn, to heal, to thrive. In this context, the St. Charles Hotel in Winnipeg’s Exchange District, a vacant building notable for its architectural character and prominent urban presence, provides an exceptional opportunity to explore how adaptive reuse can respond to both subjective and collective memory and the need for care. At the same time, healthcare environments offer a lens for exploring how architecture can embody healing; a practice that goes beyond the building itself, toward mending and caring. Historically, hospitals functioned not only as places of treatment but as civic landmarks and social anchors during moments of crisis, fostering a shared sense of care and belonging. Contemporary facilities, in their pursuit of efficiency, are too often consumed by sterility, uniformity, and control, dulling the very vulnerability at the heart of healing. Adaptive reuse provides a timely response, transforming decay into continuity and sterile facilities into civic anchors that restore memory, care, and community. In this light, architecture becomes more than infrastructure, it becomes an experience and practice of belonging.

1.This research draws on David Leatherbarrow’s notion of relative permanence, which frames architecture as both enduring and mutable over time.

Bibliography:

Leatherbarrow, David. “Relative Permanence.” Journal of Architectural Education (1984) 72, no. 2 (2018): 212–15. doi:10.1080/10464883.2018.1496729.