Rhys Wiebe

Advisor: Brian T. Rex

A Beholder’s Share

Under thing theory, things are the manifestations of objects that we actually encounter day to day. One may be reminded of the ‘thingness’ of an object when its physicality asserts itself into your experience; you look through a window as if the glass is not there, yet the smudges or distortion of light may interrupt your gaze nonetheless.1

“Temporalized as the before and after of the object, thingness amounts to a latency (the not yet formed or the not yet formable) and to an excess (what remains physically or metaphysically irreducible to objects).”2

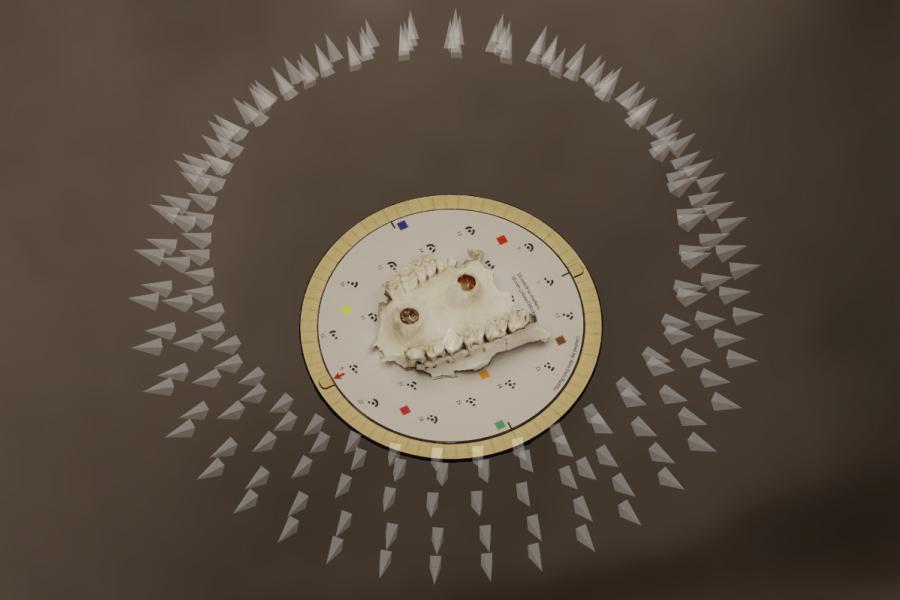

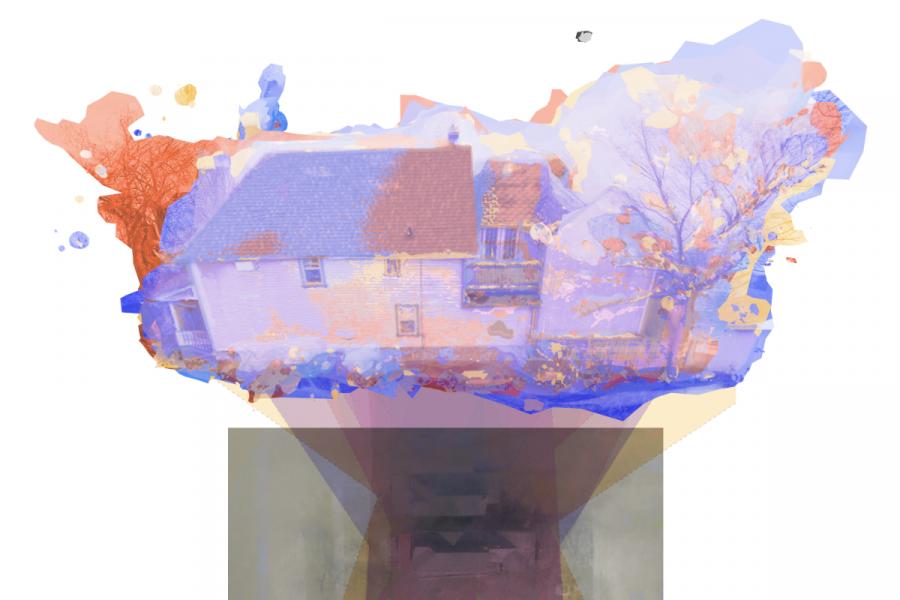

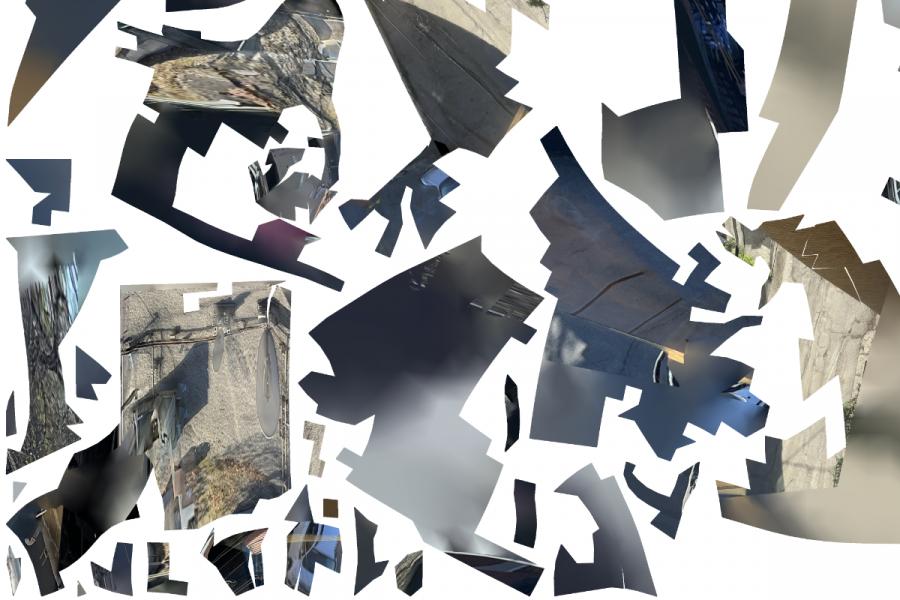

Latency and excess: there is something there before you can reduce it conceptually to an object, and there is something left on the table that cannot be reduced. A photograph of an object struggles to capture its ‘thingness’. All too often the thingness of the subject in the photo is obscured by the thingness of the photo itself; the size and reflectivity of the paper, the fidelity of the image, or the flattening of depth. Photogrammetry and other ‘reality capture’ technologies such as LiDAR enjoy many properties of photographs while adding several of their own such as depth, dimension, and, as digital objects, infinitely many points from which to view it. These mediums have their own sort of thingness which obscure that of the subject; error, fragmented surfaces, or fuzzy points. However, I would conjecture that these limits lie parallel to the limits of our own vision in that they both use images from multiple angles to compute depth. The curious aesthetics of the reality capture product mirrors the fuzziness and fallibility of our own perception.

In all creative fields, but particularly in architecture, work moves through multiple mediums and at each stage a different audience interacts with it. The digital outcomes of reality capture lend themselves to being manipulated, massaged, worked, and indeed often require it. How do we encode depth in a drawing or photograph? How can a model anticipate being flattened into a photograph included in a portfolio? Once we have captured an object digitally, how can we bring it back into the physical world? Why would we?

Moreover, in all these cases there is a beholder’s share, a participation of the audience in constructing and interpreting the visual data they receive. Often this is a reflex, learned and coded by evolutionary pressure and now by mass media. Can representation ‘hijack’ this reflex and cause one to reorient their process of seeing?

1.Bill Brown, “Thing Theory,” Critical Inquiry 28, no. 1 (October 31, 2001): 1–22, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1344258. 4.

2.Ibid. 5.